The 2020 Atlantic hurricane season is off to a frenetic start, and based on the latest long-range outlook from AccuWeather's hurricane experts, there is plenty of tropical activity still to come.

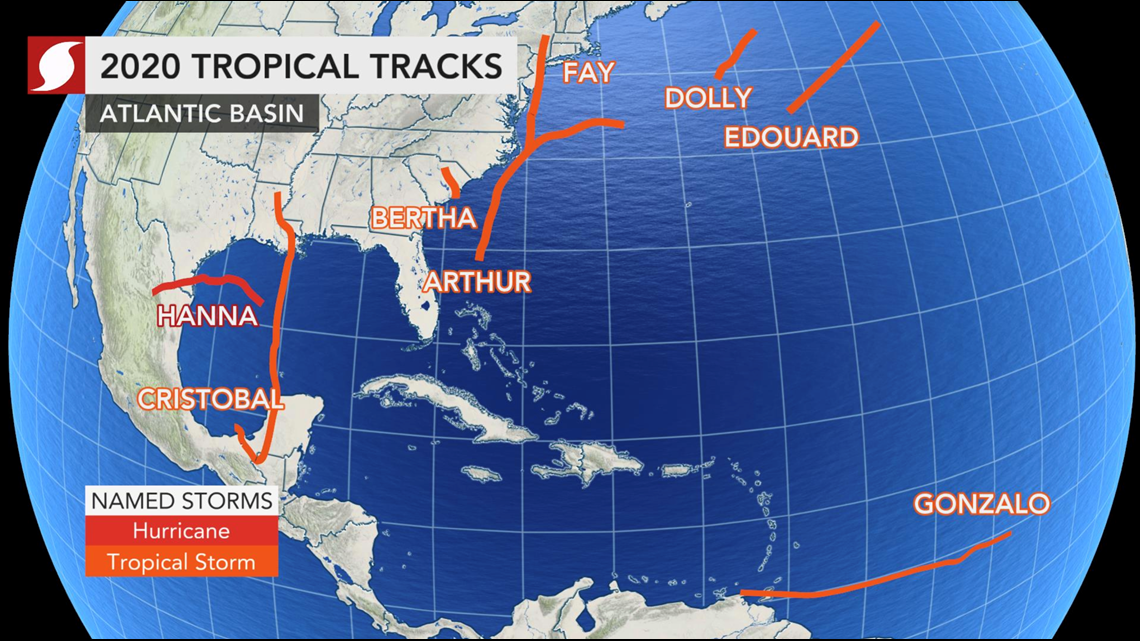

Since AccuWeather released its initial forecast back in the early spring calling for an above-normal season, the Atlantic basin has generated a whopping nine named storms through July 29. That is well ahead of the normal pace considering the historical average number of named storms by July 31 is about one, according to data from Colorado State University.

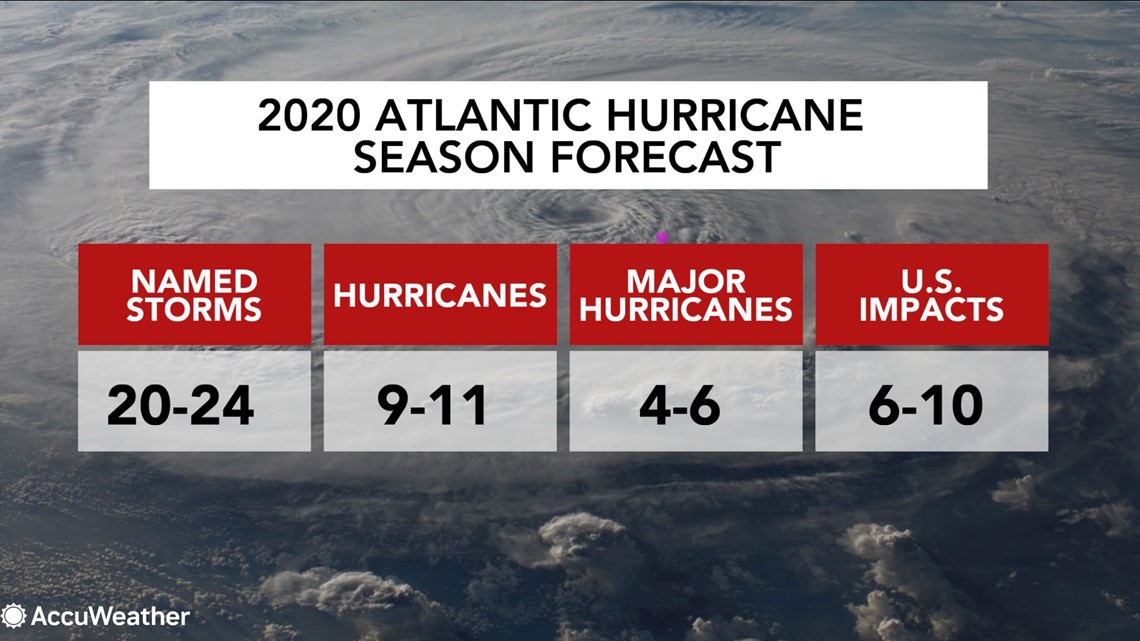

With such an active start and the heart of the hurricane season around the corner, AccuWeather's hurricane team is increasing its forecast for the number of named tropical systems during the 2020 season. The team, led by veteran meteorologist Dan Kottlowski, is now projecting 20-24 named tropical storms, of which nine to 11 are expected to become hurricanes.

The forecast of four to six major hurricanes -- Category 3 or stronger -- remains the same, but another parameter the team has adjusted is the number of direct impacts on the U.S. This was bolstered to call for anywhere from six to 10 direct impacts, up from four in the last forecast. Already this year, there have been five direct impacts and four systems that have made landfall on the U.S. mainland. The most recent was Hurricane Hanna, which crashed ashore along the coast of southern Texas on July 25 and is the only hurricane to develop so far in the Atlantic.

"That's very remarkable through July," Kottlowski said. "It's very unusual for us to see that many impacts, landfalls especially, so early in the season."

The company's initial forecast in March called for 14-18 tropical storms, seven to nine hurricanes and two to four major hurricanes. After a review of new forecasting data in May, projections were increased to 14-20 tropical storms, seven to 11 hurricanes and four to six major hurricanes.

A normal season consists of 12 named storms, six hurricanes, three major hurricanes and about three-and-a-half direct impacts.

AccuWeather meteorologists say the projected atmospheric and oceanic conditions in the coming months favor a higher-than-normal chance of at least one high-impact storm or hurricane making landfall on U.S. soil, which includes the U.S. Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico.

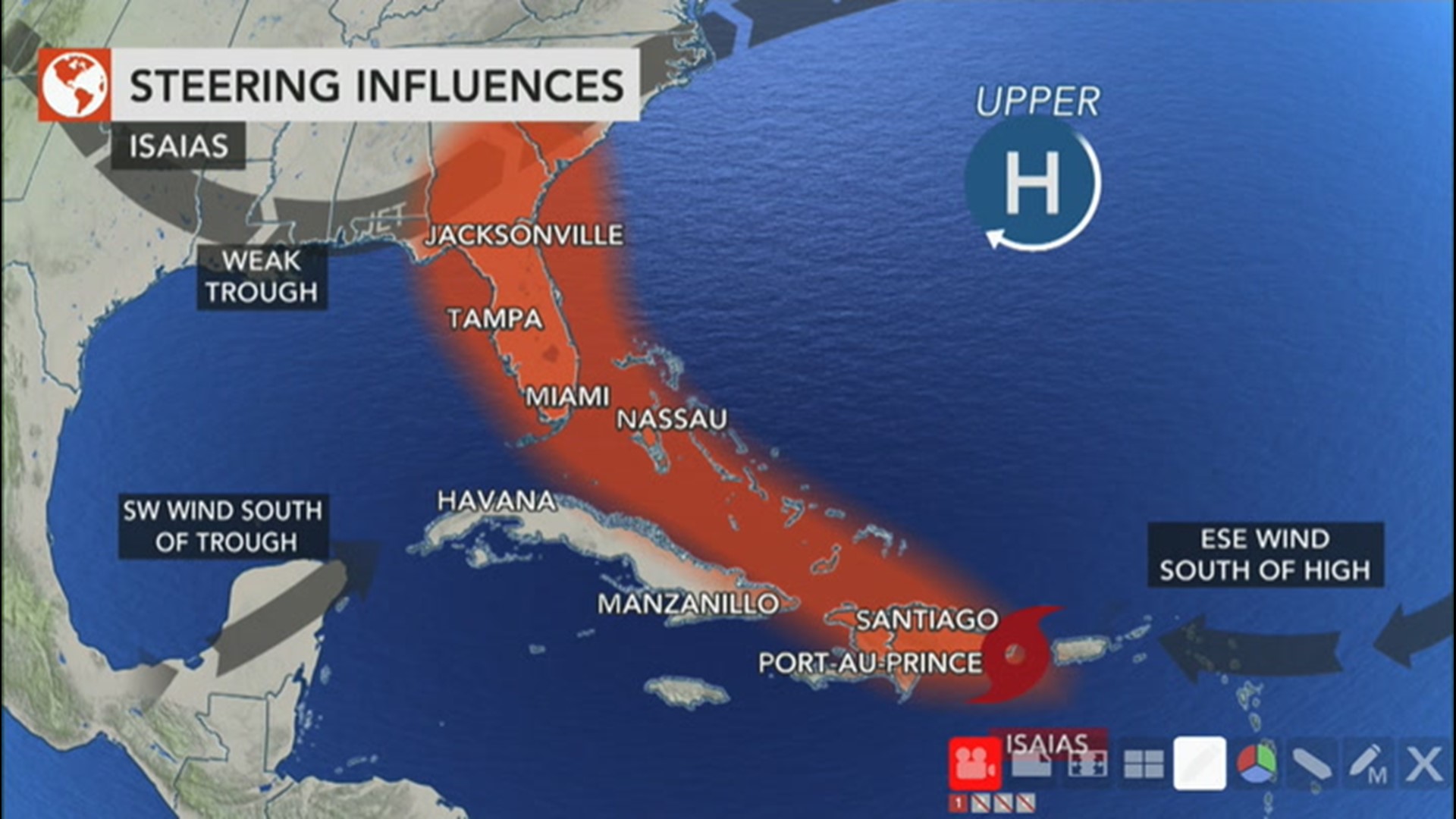

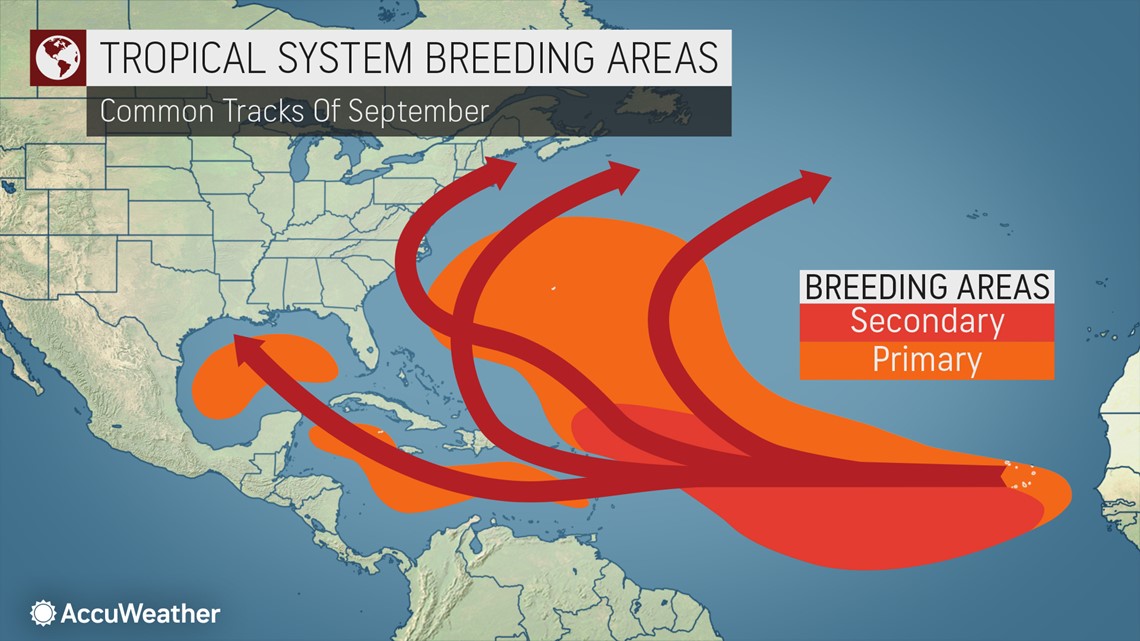

Based on past climatic data, known as analog years, AccuWeather meteorologists have emphasized that this will be an active year for Texas, Florida and the Carolinas, as the greatest potential for direct impacts from tropical storms and hurricanes will occur from the western and northern Gulf of Mexico, all of Florida and the Carolina coasts. In addition to Hanna's landfall in Texas, the Carolinas were impacted by tropical storms Arthur and Bertha in May. And Isaias could target Florida this weekend.

"I think the opportunity is there for one or two storms to threaten the Northeast coast as well," Kottlowski said. The region already dealt with one system so far this year, when Tropical Storm Fay made landfall in New Jersey and spread flooding rainfall across parts of the Northeast in early July.

Analog years are past hurricane seasons that meteorologists analyze because they feature weather patterns similar to current and projected weather patterns. Meteorologists studying the tropics often use these to estimate possible future trends and impacts during a hurricane season.

Kottlowski and his colleagues say there is a high potential that this season could become "hyperactive" and may rival the historic 2005 season, which produced 28 storms (including one unnamed subtropical storm added during a post-season analysis) and included the notorious hurricanes Katrina, Rita and Wilma.

Among the developmental factors that could generate increased tropical activity are the sea surface temperatures in the primary tropical development zone in the Atlantic and the transition to a weak La Niña pattern.

The El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) pattern is a periodic fluctuation in sea surface temperatures in the central and equatorial Pacific. Currently, the ENSO pattern is in a neutral state, but forecasters expect the pattern to trend toward a La Niña pattern during what is historically the most active time for hurricanes to form. La Niña is a weather pattern that occurs when water temperatures are lower than normal in the eastern half of the equatorial Pacific.

Hurricane seasons are more active in the Atlantic when a La Niña pattern is present because it tends to bring a decrease in the strong westerly winds that create wind shear that can inhibit the growth of tropical systems. There are multiple forms of wind shear, but vertical wind shear is the most common. It is the change in direction and speed of winds at increasing heights in the atmosphere, typically between 5,000 and 40,000 feet, and can cause a tropical system to unwind or become tilted in the opposite direction in which it was initially moving.

"What happens in a La Niña is the shear is more fragmented, less frequent, and so you have much more opportunity for tropical development across the basin. That's what we think will be the case at least for the next three months," Kottlowski said.

Yet another indicator that an active August and September and even October are ahead is the forecast for sea surface temperatures. These temperatures are expected to be above normal across the main development region for tropical systems in the Atlantic.

"There should be regions of deep, warm water across the basin which will support rapid intensification and the development of four to six major hurricanes," Kottlowski said.

Once a tropical system has developed into a storm or hurricane, whether or not it sets a path toward the United States often comes down to the strength, orientation and central position of an area of high pressure over the Atlantic known as the Bermuda-Azores high.

That high has been very strong over the past several weeks, a player that helped Hanna to develop and a culprit behind so much activity in the Gulf of Mexico so far, Kottlowski explained. However, that high pressure area tends to relax a little bit and change orientation at times during August and September and even into October, he added. Kottlowski stressed that this change "allows for a weaker trade wind flow leading to warmer water and more opportunity for storms to recurve toward the U.S."

In October, the high sometimes moves farther east, allowing storms to move much closer to the East Coast of the U.S., north of the Carolinas.

"I'm very worried that it's very possible given how warm the water is and how the pattern is setting up, that the East Coast, even all the way up to New England, should be very, very vigilant of what we see happening," Kottlowski said.

Not only will this year turn out to be more active than normal, but the intensity of the season will be greater than average.

Forecasters determine a hurricane season's intensity by a metric known as Accumulated Cyclone Energy, or ACE. ACE is used to express the activity of individual tropical cyclones and entire seasons. ACE accounts for a storm's individual strength and duration and is calculated by taking an approximation of a storm's wind energy over its lifespan and calculated every six hours.

The ACE value for this season is expected to be in the 170-200 range, well above the normal value of 106. In 2019, the ACE value was 119, while during the 2005 season, the ACE value was a whopping 245.3, according to Colorado State. In the 2017 season, which produced major hurricanes Harvey, Irma, Maria and Jose, the ACE total was 224.

ACE helps forecasters place things in perspective with regard to the coming peak, according to Kottlowski.

"The ACE that we're forecasting is not as high as in 2005, or in 1995, which were two very active seasons," he said. "However, it doesn't matter if you're hit with a very, very strong hurricane. One hurricane can cause phenomenal damage to a coastal area."

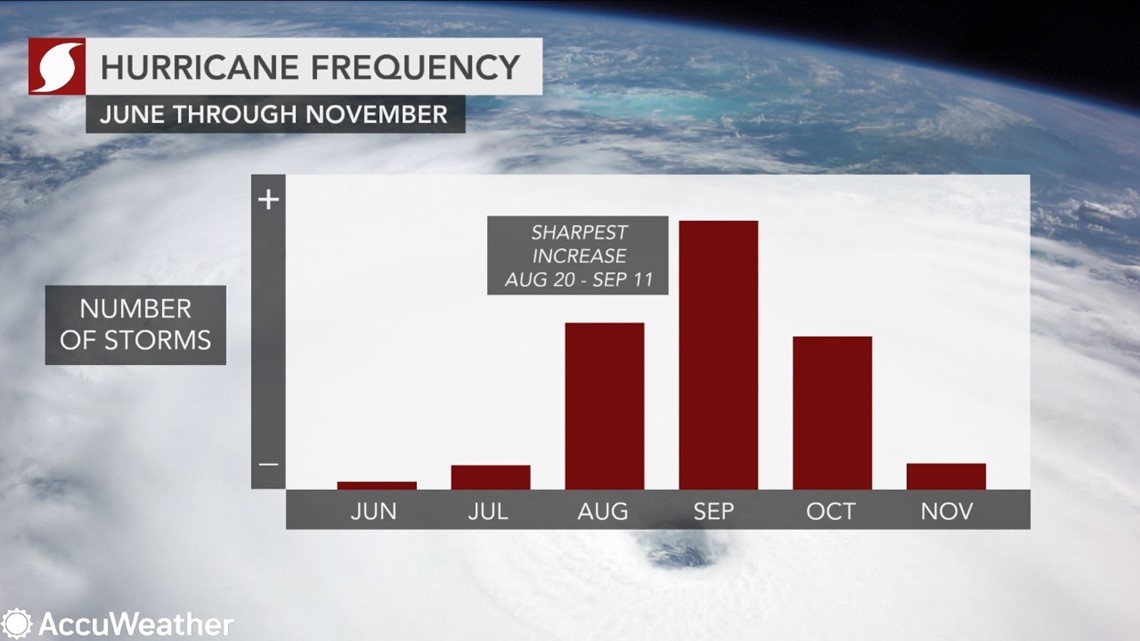

The statistical peak of the hurricane season, which goes until Nov. 30, is traditionally around Sept. 10. However, some years the season could peak in early or late September, according to Kottlowski. The most intense and damaging storm in 2019, Dorian, occurred right in this specific timeframe with a lifespan of Aug. 24 to Sept. 7.

Kottlowski emphasized his concern for a high-impact storm to strike the U.S. later this season due to aforementioned factors such as La Niña and above-normal water temperatures. Despite the abundance of storms that have formed so far, Hanna was the only one to impact the U.S. that is considered "high impact," after it triggered damaging flooding in Texas.

"My biggest concern is that the worst of the storms start developing in August," Kottlowski said. "As we go into August and September, we're dealing with stronger storms and [greater] probability that we'll have major hurricanes to deal with through the rest of the season."

And on top of complicating the response to natural disasters amid the coronavirus pandemic, 2020 may throw yet another curveball with the tropical Atlantic potentially churning out threats later in the season than normal. Typically, there aren't many powerful tropical systems that target the U.S. in November as tropical activity normally begins to wane during the month. However, it's "very possible" that November will be more active than normal this year due to the expected transition to La Niña and with the latest forecast calling for up to 24 storms, according to Kottlowski.

The 2005 season was the last time the Greek alphabet had to be used. In that year, there were six Greek-named storms, including Tropical Storm Zeta, which formed on Dec. 30. In 2019, only one tropical storm, Sebastien, formed in the basin during November, while there were none in November 2018. The last hurricane in November was Otto, which impacted Central America in 2016.