(PARRIS ISLAND, S.C.) -- Anyone who wants to be one of 'The Few, The Proud' must first get past a Marine Corps drill instructor.

'DI's,' famous for Smokey Bear hats and bad attitudes, are charged with taking raw recruits, and in 12 weeks, transforming them into America's elite warriors.

Drill instructors hold a prestigious position in the Corps. Standards for physical fitness and leadership skills are high, and a near-spotless military record is required. A stable family life is preferred, and over 80% of DI's are married.

DI's have one of the most demanding jobs imaginable. Rising at '0430 hours' most days and working late into the night, drill instructors work up to 120 hours per week, and often get only a few hours of sleep at night for weeks on end.

Since they set the pace for the difficult recruit training regimen, DI's must be in exceptional physical condition. They also receive extensive training in first aid and CPR.

While any fitness trainer can whip soft bodies into shape, Marine DI's must also instill the basic values of the Corps into their recruits, and help them master of a broad range of military skills.

During the 12-week training period, instructors teach marching drills, marksmanship, swimming, military history, martial arts, and numerous other military skills and life lessons.

The psychological and cultural transformation recruits undergo requires an extraordinarily skilled, and tough, teacher.

There is no 'I' in 'platoon'

Recruits do nearly everything as a unit, on command. These recruits were just instructed in how to properly angle the elbow while drinking from their canteen. One was later scolded for replacing the canteen cap without being told to do so.

The hardest phase of boot camp for both recruits and instructors is the first three weeks. That's the period when recruits must embrace the concept of being part of a unit and accept the responsibility for the actions of their fellow recruits. It can be a tough transition for young people raised in the 'me first' culture of America.

Staff Sergeant Joseflynn Rodel, a veteran drill instructor from Lake City, S.C., said that the overriding goal is to build a sense of team.

'We want recruits to learn that their individual actions affect not just themselves, but the whole platoon, the whole unit. When they leave boot camp, they need to have the strong confidence and trust that they can rely on each other when they go out to defend our country,' said Rodel.

A primary goal of boot camp is to strip away individuality. As new recruits arrive at Parris Island, personal possessions and civilian clothing are handed over. Hair is cut down to the skin. Each recruit is issued the same items, and only those essentials the Marine Corps feels they should have.

First person pronouns are forbidden. Recruits must refer to themselves only as 'this recruit,' and they may not look their drill instructor in the eye.

Many recruits wear a permanently stunned look on their face their first few weeks on Parris Island.

Black Belt Daddies

There are four drill instructors assigned to each platoon. Three assistant DI's are known as the 'green belts,' and the Senior Drill Instructor (SDI) wears a black belt. These belts are not related to the colored belts earned in the martial arts.

The SDI, informally known as the platoon's 'daddy,' has a unique role. While the green belts are focused on the nuts and bolts of daily training, the SDI directs the training schedule and has primary responsibility for recruits' well being.

The SDI listens to recruits' problems, sees that injuries receive medical care, and decides which recruits move on to the next phase of training.

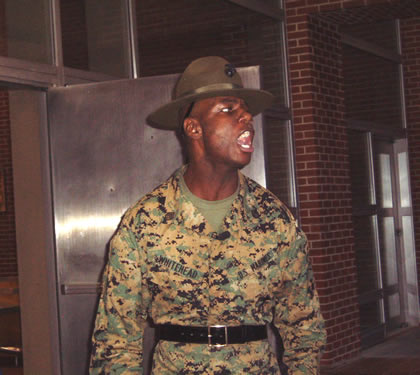

Smokey Cover

Staff Sgt. Joseflynn Rodel is a drill instructor at Parris Island Marine Corps Recruit Depot, South Carolina.

The trademark of the DI is the famous Smokey hat, or in military parlance, the 'campaign cover.' The distinctive hat is worn only by DI's and Primary Marksmanship Instructors, and it's a universal symbol of authority among all Marines, since even future officers are trained by DI's.

The campaign cover screams authority to a Marine as much as a general's stars. That aura of authority is illustrated by traffic safety banners posted along the streets of some Marine bases. They feature the image of a drill instructor barking commands such as 'SLOW DOWN, MARINE' and 'I'M WATCHING YOU, PUT ON THAT SEAT BELT.' Somehow, the image of the base's fatherly commanding officer delivering the same orders would not seem as effective.

'There's a certain attitude you take on when you wear the campaign cover,' said Staff Sgt. Rodel. 'It's worn with pride, of course, and it also comes with a big responsibility.'

Rodel added that the angle at which the campaign cover is worn is all-important. Cocked slightly forward, it comes at recruits at a menacing angle, and often hides the DI's eyes from the recruit.

Forward March

If the symbol of the drill instructor is the campaign cover, the trademark of the individual DI is his cadence. Drill instructors are taught the basics of calling cadence in DI school, such as 'left-right-left.' But from there, cadence becomes a form of personal expression.

One of the most important objectives of Marine basic training is teaching recruits to operate as a team.

No two DI's use the exact same cadence, and some adopt a musical 'sing-song' cadence.

'Recruits really appreciate their drill instructor's cadence. It's actually used as a motivational tool. They respond to their drill instructor's unique cadence,' said Staff Sgt. Rodel, who added that the style of cadence often depends on the DI's role.

'The green belts' job is just to get the recruits from point A to point B. Recruits may hate it if he uses just 'left, right left,' but it doesn't matter, that's the Assistant DI's job. The Senior Drill Instructor, wearing the black belt, can sing to them and motivate them because that's his job. The recruits are going to love him for that because he gives them more, whereas the green belts don't give them a thing,' said Rodel.

There are other parallels between music and marching cadence, which after all is primarily a matter of tempo. DI's are taught that marching cadence should be at 120 beats per minute, while running cadence is 160.

'Running cadence is more musical and has more rhymes,' said Rodel.

Often the verses are amusing, patriotic, or borderline bawdy, and recruits loudly sing back each line to the DI, no doubt motivating the trainees to keep up the pace for another mile.

Frog Voice

Boot camp involves a lot of yelling. In addition to calling cadence during runs and marching, DI's constantly yell commands at recruits, and recruits are usually expected to reply with an equally loud 'Aye, sir.' All that yelling can take a brutal toll on the DI's voice. Many adopt a peculiar, menacing growl known as the 'frog voice.' Think of the late disc jockey Wolfman Jack in an extremely foul mood.

You'd assume that DI's talk in this manner because the yelling has damaged their vocal cords. While this is sometimes the case, experienced drill instructors say the frog voice is also a means of protecting the vocal cords so they can withstand the stress of nearly constant yelling, 16 hours a day for weeks on end.

Some DI's use throat lozenges and drink hot tea, but in DI school, instructors are taught that the preferred method of preserving the voice is by talking from the diaphragm rather than the throat.

'People destroy their vocal cords talking from their throat,' said Staff Sgt. Rodel. 'No matter how you use your voice, it's going to wear out from the repetitiveness of yelling day in and day out. But you'll have a lot more of your voice left after boot camp if you talk from your diaphragm.'

For whatever reason it's used, the DI frog voice will no doubt echo in the recruits' brains for decades.

From recruit to Marine

Drill Instructors are the constant driving force in recruits' lives for all 12 grueling weeks of basic training. Recruits are told when and where to stand, sit, eat, drink, talk, walk, and run. The DI tells recruits what to wear, when to wear it, when to go to the 'head,' and how long to stay there.

Recruits quickly understand that their main job is gaining the approval of their DI's. Yet for the first few weeks of boot camp, no action they take and no answer they give seems to be correct.

However, over the course of boot camp, approval gradually comes, and recruits build confidence as they master the phases of training.

Gunnery Sgt. Adrian Tagliere instructs a recruit who has just completed an event in the Leatherneck Square confidence course. The recruit is in his 15th day of training.

During the Crucible, which amounts to a grueling 'final exam' for basic training, DI's begin to relate to the recruits in a different manner. For the first time, recruits are not given orders in minute detail, but instead are given tactical challenges which they are expected to solve as a team with their fellow recruits. DI's begin to instruct the recruits with slightly less ferocity, and act more as mentors.

The transformation culminates a few days later in the Eagle Globe and Anchor Ceremony, held one day before graduation, when the DI for the first time calls recruits by their name, and by their new title, Unites States Marines.

It's a safe bet that no Marine will ever forget his or her drill instructor.

'I've had several former recruits who have e-mailed me back, a couple of them from Iraq and Afghanistan, and they said, 'We didn't understand it when we were in recruit training, but we get it now,'' said Staff Sgt. Rodel. 'But you don't do it for that. You do it because you're taking a kid from society and turning him in to somebody that the country respects. The rewards are long-term.'

Nice guys. Really.

While recruits might initially think of their DI's as raving maniacs, drill instructors encountered away from their platoons are almost always exceedingly polite and pleasant company. Perhaps it's because they've expended all their negative energy on their platoons, but it's a side of a DI which would no doubt amaze their young recruits.

Occasionally, the Corps requires drill instructors to perform special duties for the good of the service. For one decorated DI recently, this included escorting a group of civilian educators from Virginia and Ohio on a tour of Parris Island and the nearby Marine Corps Air Station in Beaufort.

When a matronly teacher from Ohio needed help, she assumed correctly that she could depend on the kindness of this Marine. 'Excuse me, sergeant,' she said to Staff Sergeant Dan Ryley, 'I think I've left the lens cap to my camera where we were taking pictures down by the river. Can you please go down there and look for it?'

Ryley, tough as nails warrior, supervisor of senior drill instructors, and the Marine Corps' Drill Instructor of the Year, did not hesitate to go above and beyond the call of duty.

As far as we know, the Marines don't award medals for manners and patience, but if they start, Ryley surely earned a spot at the front of the line.