TERRE HAUTE, Ind — Orlando Hall got stiffed on a drug deal and went to a Texas apartment looking for the two brothers who took his money. They weren't home, but their 16-year-old sister was.

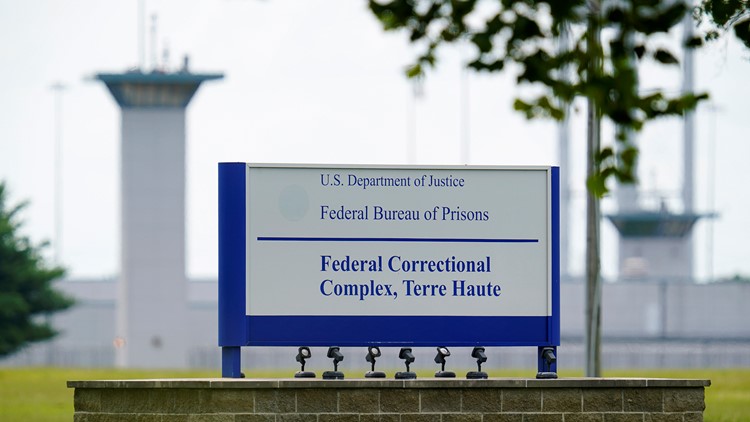

Late Thursday, Hall was put to death for abducting and killing the teenager, Lisa Rene. His was the eighth federal execution this year since the Trump administration revived a process that had been used just three times in the past 56 years. A judge’s stay over concerns about the execution drug gave Hall a reprieve, but for less than six hours. After the Supreme Court overturned the stay, he was put to death just before midnight.

Hall, a changed man in prison according to his lawyers and a church volunteer who had grown close to him, was consoling his family and supporters at the end. “I’m OK,” he said in a final statement, then adding, “Take care of yourselves. Tell my kids I love them.”

As the drug was administered, Hall, 49, lifted his head, appeared to wince briefly and twitched his feet. He appeared to mumble to himself and twice he opened his mouth wide, as if he was yawning. Each time that was followed by short, seemingly labored, breaths. He then stopped breathing. Soon after, an official with a stethoscope came into the execution chamber to check for a heartbeat before Hall was officially declared dead.

Hall’s attorneys also had sought to halt the execution over concerns that Hall, who was Black, was sentenced on the recommendation of an all-white jury. The Congressional Black Caucus asked Attorney General William Barr to stop it because the coronavirus “will make any scheduled execution a tinderbox for further outbreaks and exacerbate concerns over the possibility of miscarriage of justice,” according to a letter to Barr.

Meanwhile, another judge ruled Thursday that the U.S. government must delay until next year the first execution of a female federal inmate in almost six decades after her attorneys contracted the coronavirus visiting her in prison. Lisa Montgomery had been scheduled to be put to death on Dec. 8.

Hall was among five men convicted in the abduction and death of Lisa Rene in 1994.

According to federal court documents, Hall was a marijuana trafficker in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, who would sometimes buy drugs in the Dallas area. On Sept. 24, 1994, he met two men at a Dallas-area car wash and gave them $4,700 with the expectation they would return later with the marijuana. The two men were Rene’s brothers.

Instead, the men claimed their car and money were stolen. Hall and others figured they were lying and were able to track down the address of the brothers’ apartment in Arlington, Texas.

When Hall and three other men arrived, the brothers weren’t there. Lisa Rene was home, alone.

Court records offer a chilling account of the terror she faced.

“They’re trying to break down my door! Hurry up!” she told a 911 dispatcher. A muffled scream is heard seconds later, with a man saying, “Who you on the phone with?” The line then goes dead.

“She was studying for a test and had her textbooks on the couch when these guys came knocking on the front door,” retired Arlington detective John Stanton Sr. recalled. Police arrived within minutes of the 911 call, but the men were gone, with Rene. Stanton still winces at the near-miss of thwarting the crime in its early stages.

“It was one that I won’t ever forget,” Stanton said. “This one was particularly heinous.”

The men drove to a motel in Pine Bluff. Rene was repeatedly sexually assaulted during the drive and at the motel over the next two days.

On Sept. 26, Hall and two other men drove Rene to Byrd Lake Natural Area in Pine Bluff, her eyes covered by a mask. They led her to a grave site they had dug a day earlier. Hall placed a sheet over Rene’s head then hit her in the head with a shovel. When she ran another man and Hall took turns hitting her with the shovel before she was gagged and dragged into the grave, where she was doused in gasoline before dirt was shoveled over her.

A coroner determined that Rene was still alive when she was buried and died of asphyxiation in the grave, where she was found eight days later.

Rene’s older sister, Pearl Rene, said in a statement that she and her family “are very relieved that this is over. We have been dealing with this for 26 years and now we’re having to relive the tragic nightmare that our beloved Lisa went through.”

Crossing the Texas-Arkansas line made the case a federal crime. One of Hall’s accomplices, Bruce Webster, also was sentenced to death, though a court last year vacated the sentence because Webster is intellectually disabled. Three other men, including Hall’s brother, received lesser sentences in exchange for their cooperation at trial.

Hall’s lawyers contend that jurors who recommended the death penalty weren’t told of the severe trauma he faced as a child or that he once saved a 3-year-old nephew from drowning by leaping into a motel pool from a balcony.

Donna Keogh, 67, first met Hall 16 years ago when she and other volunteers from her Catholic church set up a program to provide Christmas presents for children of inmates at the federal prison. They have corresponded ever since.

She doesn’t understand what executing Hall accomplishes.

“My faith tells me that all life is precious and that includes the lives on death row,” Keogh said. “I just don’t see any purpose.”

Five of the first six federal executions this year involved white men; the other was Navajo. Christopher Vialva, who was Black, was put to death Sept. 24.

Critics have argued that executing white inmates first was a political calculation in a nation embroiled in racial bias concerns involving the criminal justice system, especially in the aftermath of George Floyd’s death in Minneapolis in May.