When Muhammad Ali died at age 74 on Friday, the once-strident, generation-defining voice of defiance that seemed cruelly muted to a barely audible whisper by Parkinson's disease was silenced forever. Or was it?

Won't America always hear Ali's words — the rhyme and the reason — ringing in its collective consciousness?

For more than half a century, Ali gave a voice to millions who otherwise would have had none. It took death to defeat "The Greatest" — Ali, the Muslim name he changed to from Cassius Clay, means "Praiseworthy One" -- but not the principles of freedom, justice and peace for which he stood.

"He was such a great man (that) boxing should be the last thing you want to remember about him," former heavyweight champion George Foreman, who lost to Ali in the famed "Rumble in the Jungle" in 1974, told USA TODAY Sports.

"The rest of us were just boxers. This man brought something (far greater). ... I think Ali was basically misunderstood. He didn't want to make any political statement — he just wanted to be recognized as a man. It's really simple: 'Just let me eat and sleep where I want.' "

Ali died of medical complications related to his debilitating disease at a Scottsdale, Ariz. hospital, not far from his home in Paradise Valley, Ariz.

Quite simply, there never has been an athlete before, or since, who shook America by the collar and made the nation pay attention the way Ali did. As Ali himself said: he was black and he was beautiful. He backed up his then-fathomable public boasting with monumental triumphs, in and out of the boxing ring.

There was the "Ali Shuffle" ... "Rope-A-Dope" ... "The Rumble in the Jungle" ... and those wacky nicknames he slapped on his ring rubes, among them: "The Bear" (Sonny Liston), "The Mummy" (Foreman) and "The Rabbit" (Floyd Patterson).

"He brought psychological warfare (to boxing) before anybody knew what it was," former lightweight champion Ray "Boom Boom" Mancini told USA TODAY Sports. "He was a genius."

But it was out of the ring as an indefatigable fighter for justice and equality for all peoples where Ali was historically incomparable. He was a forceful proponent of civil rights, black empowerment and social justice.

He will be remembered not so much because he was the first man to win the heavyweight crown on three occasions, or for his magnetic aura, but as someone who boldly sabotaged his career at its zenith. He walked away from one of the most-powerful positions in sports when he willingly was stripped of his heavyweight crown in 1967 for refusing military induction during the Vietnam War.

Refused induction into military

As Cassius Clay, which Ali called his "slave name," he was raised a Baptist in a lower-middle class neighborhood of Louisville and had limited formal education. He was an enormously gifted, dedicated athlete who was encouraged to take up the sport by a Louisville policeman who operated a boxing gym.

Thus began an unprecedented, extraordinary journey from humble beginnings in the segregationist South to gold medalist in the light-heavyweight division at the 1960 Rome Games to world-wide acclaim as a conqueror of Liston, Foreman and Joe Frazier in epic ring confrontations.

As Clay, he stunned the boxing world in 1964 with an upset of heavyweight champion Liston, a 7-1 favorite, in Miami Beach. Subsequently, befriended by civil rights activist Malcolm X, Clay changed his name to Ali and his allegiance to the Nation of Islam. Eventually, his metamorphosis prompted Ali to eschew his black-separatist views of the turbulent '60s and seek spiritual enlightenment by adopting the non-violent values of traditional Islam.

The seminal moment came April 28, 1967, when Ali steadfastly refused to step forward — on three separate occasions — for his U.S. Army induction in Houston. He had asked the government to reclassify him as a conscientious objector based on his religion. The U.S. Justice Department denied it.

Three years earlier, Ali had been classified as not military-ready after a low score on the Army intelligence exam. ("I said I was The Greatest — I never said I was the smartest," he later quipped.) In 1966, he was reclassified as fit for service.

It had been his religious and social convictions that led Ali to famously conclude, "Man, I ain't got no quarrel with them Viet Cong," later explaining, "No Viet Cong ever called me a nigger."

Ali was arrested. The World Boxing Association quickly defrocked him as champion and state commissions rescinded his license to fight.

At his trial the following year, Ali was found guilty, sentenced to a maximum five years in prison and fined $10,000. A series of legal battles ensued, with Ali ultimately receiving vindication from the U.S. Supreme Court, based on a technicality, four years later.

He did not box for 3½ years. His triumphant comeback was completed Oct. 26, 1970, when he bludgeoned Jerry Quarry with a third-round stoppage to reclaim the lineal title in Atlanta (Georgia had no boxing commission).

During his exile, Ali explained his righteous indignation at America's establishment during speeches at colleges and universities. Eventually, the tide of opinion turned against the war in Vietnam.

"Outside the ring — what he stood up for, what he believed in, what he sacrificed for — gave every minority hope," Hall of Fame fighter Sugar Ray Leonard told USA TODAY Sports.

PHOTOS: Charisma of Ali

![30 photos of Muhammad Ali in all his charismatic glory [gallery : 2102169]](http://www.gannett-cdn.com/media/USATODAY/USATODAY/2013/04/22/xxx-ap621115078-front_thumb.jpg)

'Student of boxing'

For three decades, Ali courageously battled Parkinson's disease without complaint or seeking pity. Exceedingly frail with an eerie stillness in recent years, he endured muscle tremors, a wobbly gait and slurred speech but he refused to hide his challenges from the public, instead serving as a source of inspiration.

It was in stark contrast to the boxer's talents in the ring and gregariousness outside it.

Ali possessed a snake-like jab, the physique of a Greek god and the improvisational skills of a jazz musician. The 6-3, 225-pound ring marvel fought more heavyweight championship rounds than any fighter in history (255) while fashioning a record of 56-5 with 37 knockouts. At 39, Ali was retired by Trevor Berbick after he lost a desultory 10-round decision in the Bahamas.

During his prime, Ali's talent, vanity and desire to become a great heavyweight overlapped the rise of bombastic broadcaster Howard Cosell. Their memorable television exchanges -- Ali once peeled back Cosell's toupee on-air -- helped propel both their careers.

As Chuck Wepner, one of Ali's vanquished opponents, told USA TODAY Sports: "He was the greatest promoter of all time — he could turn a fight between a lion and a duck into a fight that looked legit," often by using outlandish predictions delivered in poetic style.

"It'll be a killa, a chilla, a thrilla, when I get the Gorilla in Manila!" was Ali's pre-fight proclamation in the build-up to his stirring 1975 triumph against Frazier in the "Thrilla in Manila," the third and final bout in their compelling trilogy.

His late trainer, Angelo Dundee, told USA TODAY Sports in 2009 that Ali often would preen in front of an old cracked mirror at the Fifth Street Gym in Miami Beach.

"He'd check himself out every day," Dundee said. "He loved the gym. A lot of fighters hate it; it's a labor but not a labor of love. This kid was a student of boxing."

Of course, Ali was far from perfect. As he aged, his desire to train properly waned. It cost him the title against a woefully inexperienced Leon Spinks, who stunned Ali by winning a 15-round decision in 1978; Ali extracted revenge later that year.

He emerged from retirement in 1980 for an ill-advised comeback against champion Larry Holmes, who pummeled him until his corner stopped the fight after the 10th round, the only time Ali was halted.

While he was not mean-spirited by nature, Ali sometimes could be oddly cruel. He relentlessly punished Ernie Terrell in their 1967 bout in Houston, battering him for 15 rounds while taunting, "What's my name?" for his opponent's insistence at calling him Clay.

Ali engaged in race-baiting, too, labeling Frazier and Patterson as "Uncle Tom(s)."

But for the vast majority of those whose lives intersected with Ali, there was nothing but mutual love.

Canadian heavyweight George Chuvalo, who Ali defeated in a 15-round decision in 1966 in Toronto, visited with Ali many times over the years.

"It was always very warm, friendly," Chuvalo recalled. "He was just a nice guy. I feel forever cemented with him."

Charitable world-wide

His medical diagnosis was made public in 1984 but Ali began to suffer symptoms years earlier. The world got a vivid glimpse into his courageous life at the 1996 Summer Games in Atlanta, where Ali, with trembling hands, lit the Olympic cauldron.

All the while, Ali was donating considerable time and effort to social causes and charitable missions throughout the world.

Among his efforts was the establishment of the Muhammad Ali Parkinson Research Center in Phoenix and the Muhammad Ali Center, an educational and cultural institute in Louisville.

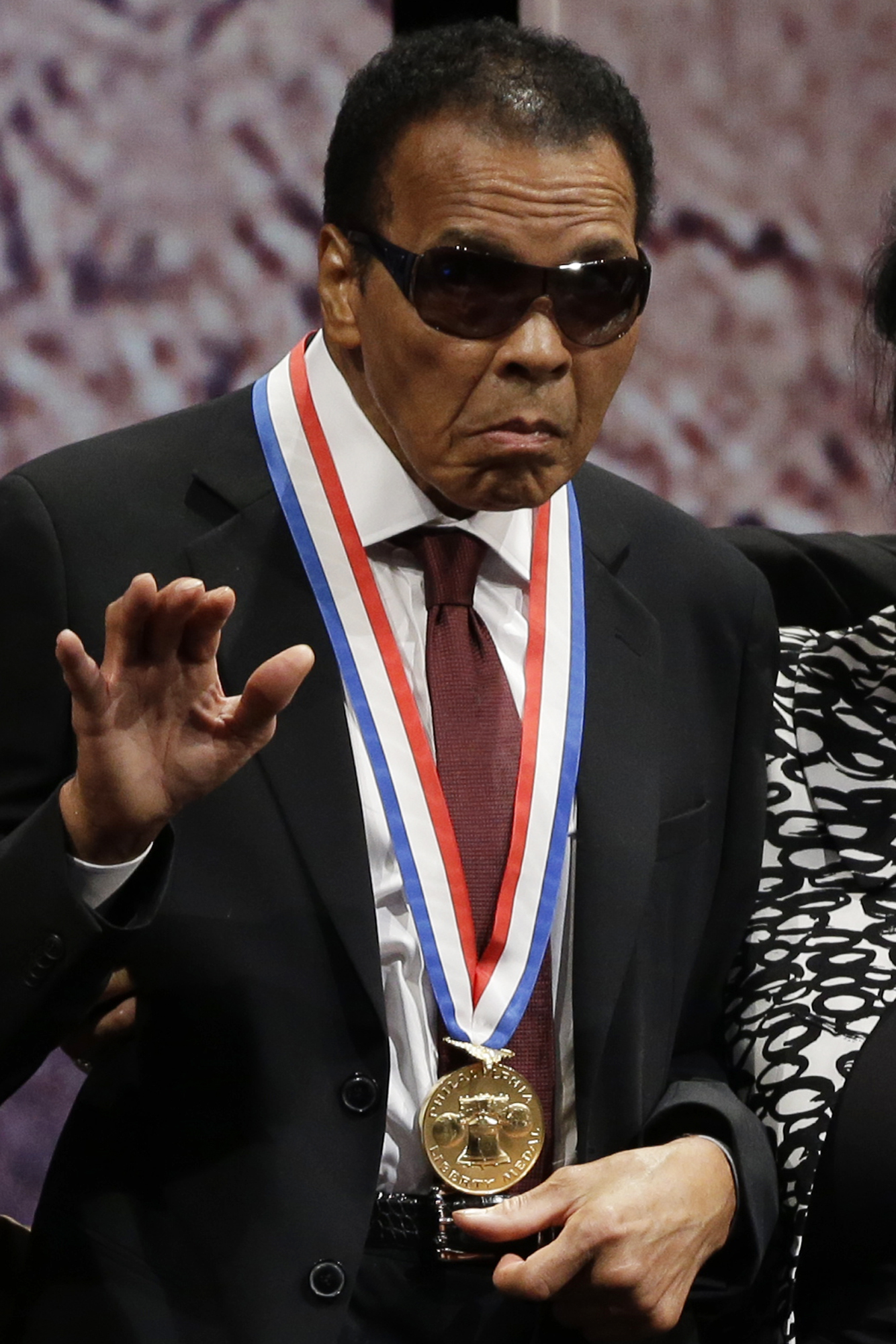

In 1998, Ali was named a United Nations Messenger of Peace by then-Secretary General Kofi Annan. In 2005, Ali was honored with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian honor, for being an "inspirational figure to millions" around the world. In 2012, the National Constitution Center awarded him the Liberty Medal for promoting worthwhile causes.

In short, Ali did much to foster world-wide respect and admiration. And touched countless lives.

Years ago, Chuvalo said, he received a phone call from a friend who said he had heard Ali had died — a bad rumor. Nonetheless, when Chuvalo hung up the phone, "I could feel the tears streaking down my face," he said.

"I realized how much I cared for the guy," Chuvalo said, eyes misting.

Friday, the world mourned with him.

The planet is now a little less humane, a little less compassionate, and a lot less fun than it used to be when Muhammad Ali floated through the world like a butterfly and stung like a bee.

PHOTOS: Ali through the years

![Muhammad Ali through the years [gallery : 1767727]](http://www.gannett-cdn.com/media/USATODAY/USATODAY/2012/12/13/xxx-ap6505250172-front_thumb.jpg)

Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr./Muhammad Ali

Born: Jan. 17, 1942, in Louisville

Nicknames: The Greatest; the Louisville Lip; the Peoples' Champion

Education: Louisville Central High School

Family: Survived by wife, Lonnie, daughters Rasheda and Jamillah (twins), Laila, Maryum, Hana, Khaliah and Miya, sons Muhammad Jr. and Asaad)

Hall of Fame: Inducted in 1990 into the International Boxing Hall of Fame

Boxing career: 56-5, 37 KOs; heavyweight champion 1964-67, 1974-78, 1978-79

Humanitarian efforts: Include helping secure release of 15 U.S. hostages in Iraq during the first Gulf War; goodwill missions to Afghanistan and North Korea; delivering medical supplies to an embargoed Cuba; meeting with Nelson Mandela after his release from prison in South Africa

Honors: Presidential Medal of Freedom, 2005; Liberty Medal from the National Constitution Center in 2012 Amnesty International's Lifetime Achievement Award; United Nations Messenger of Peace 1998-2008 for work with developing nations; USA TODAY Sports' athlete of the 20th century

Author:The Soul of a Butterfly: Reflections on Life's Journey (with Hana Yasmeen Ali), 2004; Healing; A Journal of Tolerance and Understanding (with Richard Dominick), 1996; The Greatest: My Own Story (with Richard Durham), 1975

Filmography: Himself in Love at Times Square (2003), Doin' Time (1985), Body and Soul (1981), The Greatest (1977), Requiem for a Heavyweight (1962, as Cassius Clay)

TV series: Himself in Touched by an Angel (1999), Diff'rent Strokes (1979), Vega$ (1979), Cos (1976), Lola! (1975), Flip (1971)

Trivia: Named after a 19th-century Kentucky aristocrat and emancipationist

In his own words

Quotes: "When you're as great as I am, it's hard to be humble."

"I'm gonna float like a butterfly, sting like a bee, George (Foreman) can't hit what his eyes can't see, now you see me, now you don't, he thinks he will but I know he won't."

"I'm so fast that last night I turned off the light switch in my hotel room and was in bed before the room was dark."

"The man who views the world at 50 the same as he did at 20 has wasted 30 years of his life." -- Ali

By Rachel Shuster