For NASA Wallops, the final frontier is the current one

16,000 successful rocket launches have taken place at the lesser-known NASA Wallops Flight Facility in Virginia.

At some point, getting to space from NASA's Wallops Flight Facility in Virginia became business as usual.

It's hard to say for sure when it became that way.

It was probably before Rocket Lab, a private aerospace company, chose Wallops to be the home of its first American Launch Complex in October.

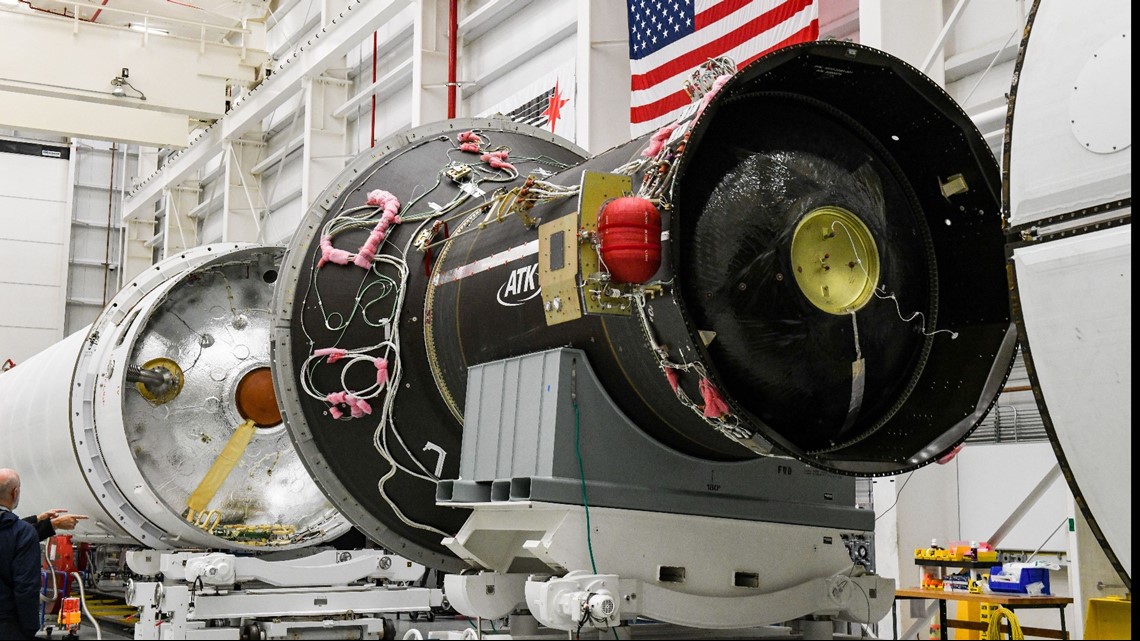

It might have been in 2013, when the first Antares rocket launched from the facility, creating a consistent series of launches at a relatively frequent interval.

Or before that — maybe in 2006, when the US Air Force launched a Minotaur rocket from Wallops Flight Facility into space.

Maybe it was before all that.

Wallops has played a key historical role in the not-so-simple task of getting an object from the Earth to the skies across the decades, from its time as an air station for the Navy to its current standing as an innovative facility that consistently does what was unthinkable just two generations ago: It goes to space.

Antares with Cygnus cargo: Cargo capsule reaches space station

That's not to say the journey has been easy, however. To many people, Wallops is the only place on the rural Eastern Shore of Virginia for those interested in math or science, although its isolated location can make it hard to retain employees.

The facility has had more than 16,000 successful launches, but some people only know of Wallops for its failures, including a 2014 rocket that crashed back down to earth just a few seconds after liftoff.

What's more, the facility is awaiting the results of an efficiencies report looking to find overlap between Wallops and its parent agency, Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. Officials say the report is not a threat to Wallops, but some people aren't so sure.

Somewhere along the line, the final frontier became the current one. The people of Wallops, through their hard work, successes and the occasional failure, have made sure of that.

Today, Wallops has full-time civil service employees as well as US Navy personnel and NOAA employees. A 2011 study from BEACON at Salisbury University (the most recent available) estimates Wallops has an annual economic impact greater than $395 million. Wallops' annual budget is about $250 million.

"Every project that comes in here tends to drive us to improve our capabilities," said Bruce Underwood, the recently retired former deputy director of the facility. "Wallops is extremely well-situated to continue to thrive."

How Wallops changed from World War II missiles to today's rockets

Wallops Flight Facility began its life under NASA's predecessor agency, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, in early 1945.

Its original purpose was developing ground-based and air-based missile systems for World War II. Officials needed a site that was close to water as well as a military installation, and Wallops Island best fit the bill.

The first test rocket was launched June 27, 1945, and the first research rocket, called the Tiamat, was launched a week later.

"By the time they really got going, the war was over," said Keith Koehler, media specialist at Wallops. "The idea was then to use these rocket systems that they'd been working with to look at aircraft, supersonic aircraft."

Supersonic aircraft were just a few years from being fully developed, and employees at Wallops helped with the design of aircraft.

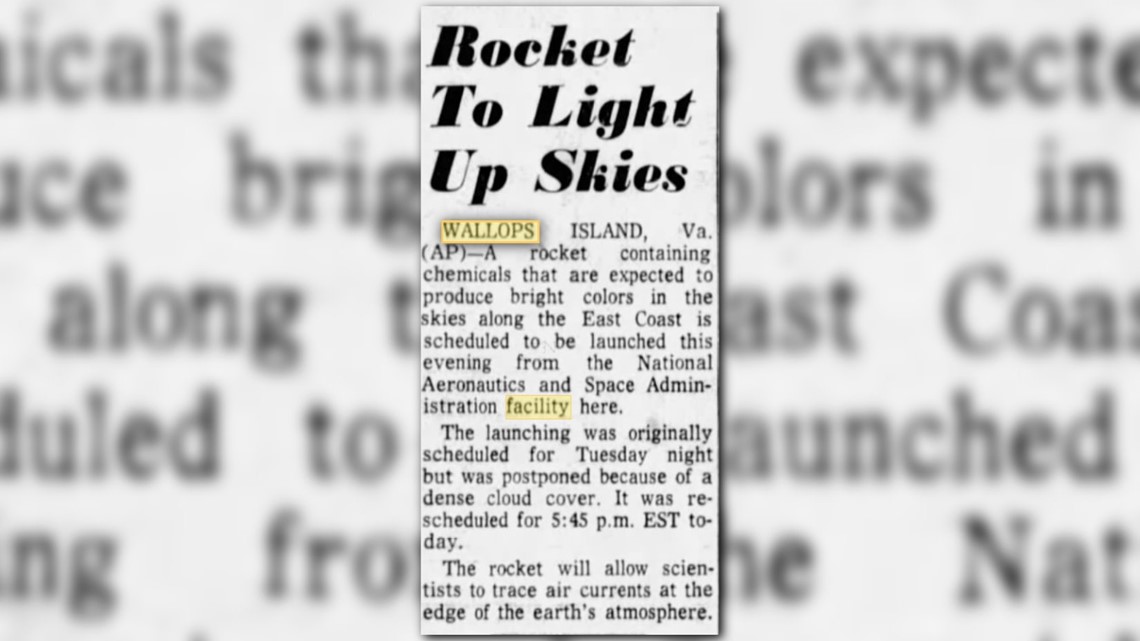

In 1958, NACA (pronounced by its letters) became NASA. Wallops became known as Wallops Station, and its mission shifted to understanding more about the atmosphere.

The next year, Wallops was looking to expand just as the Navy was closing the nearby air station at Chincoteague, where former president George H.W. Bush was once stationed. NASA took over the air station, now known as Wallops' main base, about 7 miles from Wallops Island.

Wallops Station supported the development of the Mercury space capsule, which was the first of the crewed space program. Testing for the escape systems and capsule was done at Wallops in collaboration with those at NASA Langley.

The facility was also key in the development of the SCOUT rockets, which were small rockets used to launch small satellites. In 1964, the facility launched its first satellite into Earth's orbit.

In the late 1960s and 1970s, Wallops moved more into aeronautics, utilizing the runways from the station's Navy days to collaborate with Langley. Airborne science missions started in the 1970s as well.

Wallops merged with NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in 1981, which was when it was named Wallops Flight Facility. It was a logical move, as the sounding rocket program (the focus of the time) was primarily based at Goddard's headquarters in Greenbelt while most of the testing happened at Wallops.

Because of Wallops' work with suborbital programs, the facility took over research with scientific balloons, now one of Wallops' core programs.

"We did science along the way," Koehler said. "We have a small group of scientists, the (Global Precipitation Measurement mission), we helped develop spacecraft for NASA, mostly related to the ocean and the environment."

On Oct. 25, 1995, the first purely commercial rocket was launched from Wallops.

Koehler said the Conestoga, as it was called, "flew great for 43 seconds" before ultimately failing. Rockets would not launch again from Wallops until 2006, when the Air Force began using Minotaur rockets to get small satellites into orbit.

The Antares program came along in 2013, creating the most steady stream of launches yet. The program overall has been a success, but there have been struggles.

On Oct. 28, 2014, an Antares rocket carrying cargo destined for the International Space Station exploded and crashed back down to the launch pad just a few seconds after liftoff.

There have been three successful launches since then (and four successful launches prior), but for many, the failed launch still stands out.

"People haven't forgotten it," Katie Cranor, deputy chief for flight safety at Wallops, said of the crash. "We work hard to make sure it doesn't happen again and that people are safe."

STEM talent recruited early

Those working at Wallops Flight Facility today have learned from the past, including failed launches, but they're wholly focused on the future.

Many of those working at Wallops are from the Delmarva Peninsula, if not from towns just a short drive from Wallops' gates. That's why for some, coming to work each day is a feeling akin to coming home.

Those with affinities for math and science have the opportunity to enter Wallops' summer programs as a high school student, and after graduation, many find themselves with full-time employment.

Lisa Johnson, diversity and inclusion program specialist, is one of those people. A native of Horntown, Virginia, she grew up with a fascination of "what's inside the gates."

"It never gets old," Johnson said. "Folks here are so creative, so skilled, and it's a family atmosphere that really makes coming to work exciting."

She values the "permanent buzz" of excitement that comes with working at such a dynamic facility.

Johnson says she gets defensive when anyone has negative things to say about Wallops, saying the people who work there have a positive economic impact, support educational efforts and are just plain good citizens.

"I could go on and on," Johnson said. "I feel like the Shore needs us. There are those who understandably look to Tyson and Perdue as the larger employers, but we as an aerospace industry, we help well to contribute to the Shore."

Despite its rural location, Wallops offers a lot to those in the immediate area. The about 1,200 people at Wallops bring talented people from across the country with expertise and jobs that pay well.

It has active internship and co-op programs that get local high school and college student in the gates and allow them to hone their skills as soon as they realize that science or engineering is what they want to do.

Shannon Bull, a junior at Salisbury University and a software engineering intern at Wallops, said she originally earned an internship at the facility this summer and was able to stay on as a part-time employee.

Each Tuesday, she drives the 50 minutes to Wallops to be part of a team of software engineers working to update a graphics system for an outdated program.

"A thing I love about Wallops is that they do science for the sake of science," Bull said. "They're an incredible, future-focused team, and it's a great thing to be a part of."

The internship program allows Wallops to nurture young talent and train potential future employees.

Many Wallops employees were once interns.

Johnson started in high school programs. Mike Cropper, aircraft operations manager, did high school internships before doing co-ops while a student at Old Dominion University. Underwood did summer internships at Wallops while in college. Bull hopes to stay on board.

The rural location can make it difficult to retain employees, however. People looking for a big city may prefer to work at Goddard's Greenbelt office or Johnson Space Center in Houston. Local employees are more apt to stick around, but the location that keeps them at Wallops is often what influences others to leave.

Wallops serves as one of the few places those interested in math, science or computer programming on Virginia's Eastern Shore can work in those fields. When people who work in those fields no longer work at the facility for whatever reason, they often leave the region.

"When I was growing up, I knew I wanted to do something heavily math- and computer science-based, but the only place on the entire Shore to use that was Wallops," Cranor said. "It's the only place to really use what I went to school for."

Watch a rocket launch up close

Wallops is about as integrated into the surrounding towns as it can be.

Homes are located about a mile and a half from the facility's launch pads. That allows the community to be more involved, but it also means that people live too close for some of the larger launches that one may see from places like Kennedy Space Center.

Because of current technologies and safety protocols, human beings aren't likely to be leaving Earth from Virginia anytime soon.

There are still plenty of launches, though. The Antares program ensures NASA will be launching rockets until at least the end of 2019. The announcement that Rocket Lab chose Wallops for its first American launch complex meant that once construction is finished, it will be sending up about one rocket per month. The facility is also courting other private companies that might be drawn to what is, for now, a relatively quiet launch space.

What's more, Wallops served as a draw for offseason tourism to the surrounding area. Its visitors' center isn't huge, but people come to learn the facility's history and see the kinds of rockets historically launched from the facility.

The launches themselves bring hundreds of people to the surrounding area, including tourist-friendly Chincoteague, during the offseason. Officials say its impossible to estimate exactly how valuable launches are to the local economy, but since the Antares program came in 2013, people have flocked to the area to watch launches.

Especially for overnight launches, like the November one, people book hotel rooms and eat at local restaurants in such impressive quantities that it provides the business needed to stay open during the tourism offseason.

"We absolutely make more money when there are launches," said Cynthia Wilder, marketing manager for Refuge Inn in Chincoteague. "The only exception to that is when they happen during the summer when there are already a lot of people here."

There's potential for problems on the horizon, however. NASA announced over the summer that it would look into ways to increase efficiencies between Wallops and the Greenbelt campus.

To many people, that was a concerning signal that jobs would be cut from the facility.

Jay Pittman, assistant director for strategy and integration at Goddard Space Flight Center, said in August that there was "no threat" to Wallops.

If jobs were lost at Wallops, it has the potential to damage the region at large, but officials from both major parties expressed their commitment in August making sure Wallops continues to thrive. Democratic Sens. Chris Van Hollen and Ben Cardin, both of Maryland, as well as US Rep. Andy Harris, R-Md.-1st, said they valued Wallops and its impact on the region. Sen. Tim Kaine, D-Va., said at the time his office would be reaching out to NASA for more information.

That doesn't mean Wallops is quite out of the woods. Steve Habeger, who worked at Wallops for the US Navy from 1980-2003 and founded the Wallops Island Regional Alliance, points out that since Sen. Barbara Mikulski, D-Md., retired in 2017, none of the three states that most care about Wallops — Maryland, Delaware and Virginia — has a member in either chamber of Congress in a power position on relevant committees to Wallops mission.

The final report was supposed to be released at the end of October, but there have been no updates on its status.

What's next for Wallops?

For now, though, Wallops will keep launching.

As many as three Antares launches are planned for next year, and Rocket Lab is expected to finish construction in the third quarter of 2019. New private costumers may be announced soon.

The people who work there value the work they do, to benefit both science and space exploration at large. The work helps to support the International Space Station and deep space exploration, as well as those back on earth.

"(The work at Wallops) matters in so many ways," Underwood said. "They are things that lead to bigger, broader discoveries. We tend to work on lower-profile programs and missions here. ... Ultimately, the things that show up in our future curriculum and schools are things that happened through the research done here, even if it wasn't real apparent that we were involved in it at the time."

The value of their work affects them on a more personal level, as well. Many people who work there say they consider themselves to be closer to their coworkers than people who work other places. In part, it's what keeps them there.

Even those who do end up leaving sometimes come back. When Johnson came back to Wallops after a few years working at a university, she ended up crying the first time she drove through the gate.

"I am just as happy here as I am at home," Johnson said.

Somewhere along the line, going to space became business as usual, and it will stay that way for as long as anyone at Wallops Flight Facility has anything to do with it.

Reach reporter Hayley Harding via email at hharding@delmarvanow.com or on Twitter @Hayley__Harding.