CHESAPEAKE, Va. — Most people can only imagine the history seen inside the wooden walls of the Cornland schoolhouse along Highway 17 in Chesapeake.

Few can still tell you the stories themselves.

'It was unique alright'

Mildred Brown didn't have the standard school commute we see today.

“You would walk, sing, hop skip, and run, any way to get to school fast you would do it. It was hard but we had fun going," Brown told 13News Now.

Brown, who is now 92 years old, still vividly remembers the eight mile walk she'd complete every morning along with her sister Clentoria Bridgers, just to get an education.

“One thing is when we were going to school we didn’t have electricity, no running water. We had a pump to pump water into a bucket and use a dipper to fill up our cup. We didn’t have water fountains, that’s what we went through to get an education," Brown said.

"We also didn't have indoor toilets!" she added.

History of the Cornland School

The Cornland school house, now situated along Highway 17 just a couple miles north of the North Carolina-Virginia state border, is believed to originally date back as early as the late 1800s. The current structure itself is known to have existed as early as 1902.

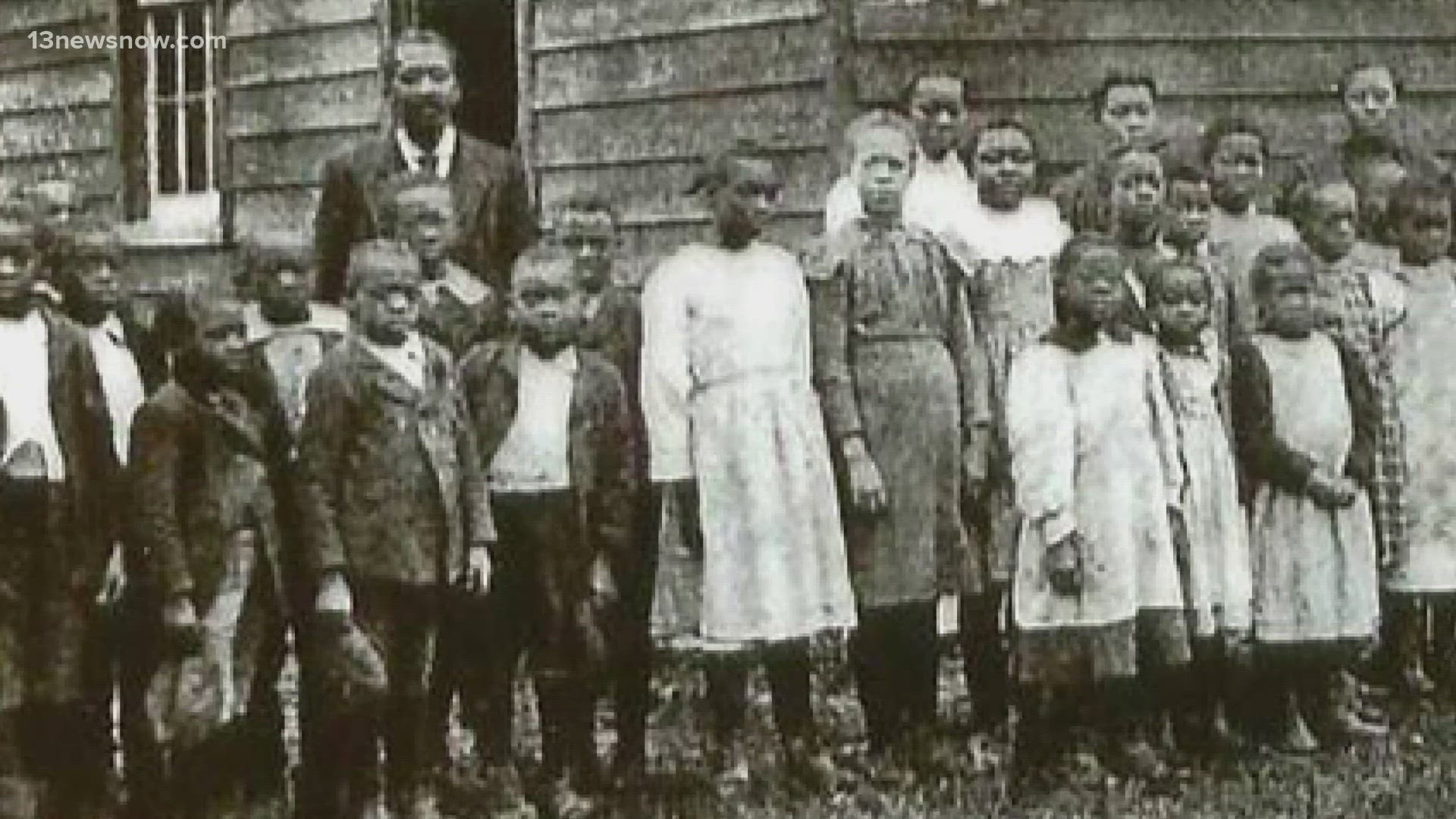

The one-room schoolhouse was built by free African Americans after the Civil War to serve African American students through segregation.

Its historical significance is amplified by the fact the Cornland school was built before The Rosenwald school building program, a progressive movement starting in the early 1910s to establish schools for Black students in the segregated South.

Over the course of decades, the Cornland school offered some of the only education available for African American students in the southern region of the City of Chesapeake.

For years, the school sat on private property falling into disrepair. The family who owned the land on which the building sat called for the help of Chesapeake City Councilwoman Dr. Ella Ward.

"We took the trip out to Benefit Road, it was just unbelievable. Pretty much buried in the woods, weeds coming out the windows. It was in real poor condition, trees all up around it. I said ‘You want me to save this?' I thought there was no way," Dr. Ward told 13News Now.

“The trees and bushes are almost covering it, what it looked like when we first saw it.”

The school was eventually moved to its current location, where it sits now under construction awaiting the completion of a months-long renovation process to transform the school into a working museum.

It's estimated more than 400 students passed through the Cornland school.

'Feel like there is a good amount of pressure'

Jessica Cosmas, Historical Services Manager for Chesapeake Parks and Recreation, is one of the many stakeholders overseeing the construction of the Cornland school.

“It's still standing which is kind of incredible in itself. A lot of these one-room schoolhouses were shut down. There were about five other schools plus Cornland that we shuttered around the same time. A lot of those buildings are not standing. So the fact that this is still standing and has stood the test of time is something that is really special," she said.

With a target date of Spring 2024, Cosmas believes the project is tracking on schedule as expected.

"Exterior lap siding, original floors, windows, and doors have been removed from the building and they are being repaired and refinished off-site. Exterior wall insulation, sheathing, and protective building wrap were also installed. Ceiling joists and rafters have been reinforced with wood framing and the chimney, built with brick reclaimed from when the school stood on Benefit, has been framed out. A new electrical panel and outlets have been installed. Concrete footers were poured for the recreated outhouses and coal shed. Foundational work to support the new ADA ramp has begun," she says.

She admits there is pressure to complete the school's construction, keeping in mind the Cornland alumni who are eagerly awaiting its re-opening.

“The alumni that we have spoken to, they have been so generous with their memories and stories. The fact they’ve been opening up about themselves, especially some painful memories, that’s not an easy thing to do."

'God made us the way he wanted us to be'

As Brown remembers, some days walking to school were better than others.

"What we had to do at home then walk eight miles in the cold. White children would ride by in the school bus, wave at you, throw things at you. One day a bus driver stopped the bus, a kid picked up a rock and threw it at us. It was hard, to see them riding and us walking and we were trying to get an education," Brown said.

“It hurt to think all of us are human, but we’re not treated like humans. We’re treated differently, just because of the color of our skins. God made us the way he wanted us to be.”

Several years ago, Cornland's still surviving alumni came together again for a picture in the early stages of the restoration project. Brown says less than half of them are still alive today.

A school worth saving

For alumna Emma Nixon, 88, preserving the school is a representation to the world of how the sacrifices of the Cornland alumni need to be cemented in history.

“It's something deep in my heart because I had to walk there, I had to walk there all those years. It's just, I just can’t explain how I feel," she says.

"I hope I live to see it finished," she added.

“That’s our heritage, we did something. Need to show our heritage, what we went through. We need something to remind people what we went through to get an education," Brown says.