NORFOLK, Va. — Throughout February, Norfolk State University is hosting a series of free virtual events to celebrate Black History Month. On Tuesday, the university welcomed back a former professor who is using art to teach a history lesson that has been left out of too many textbooks.

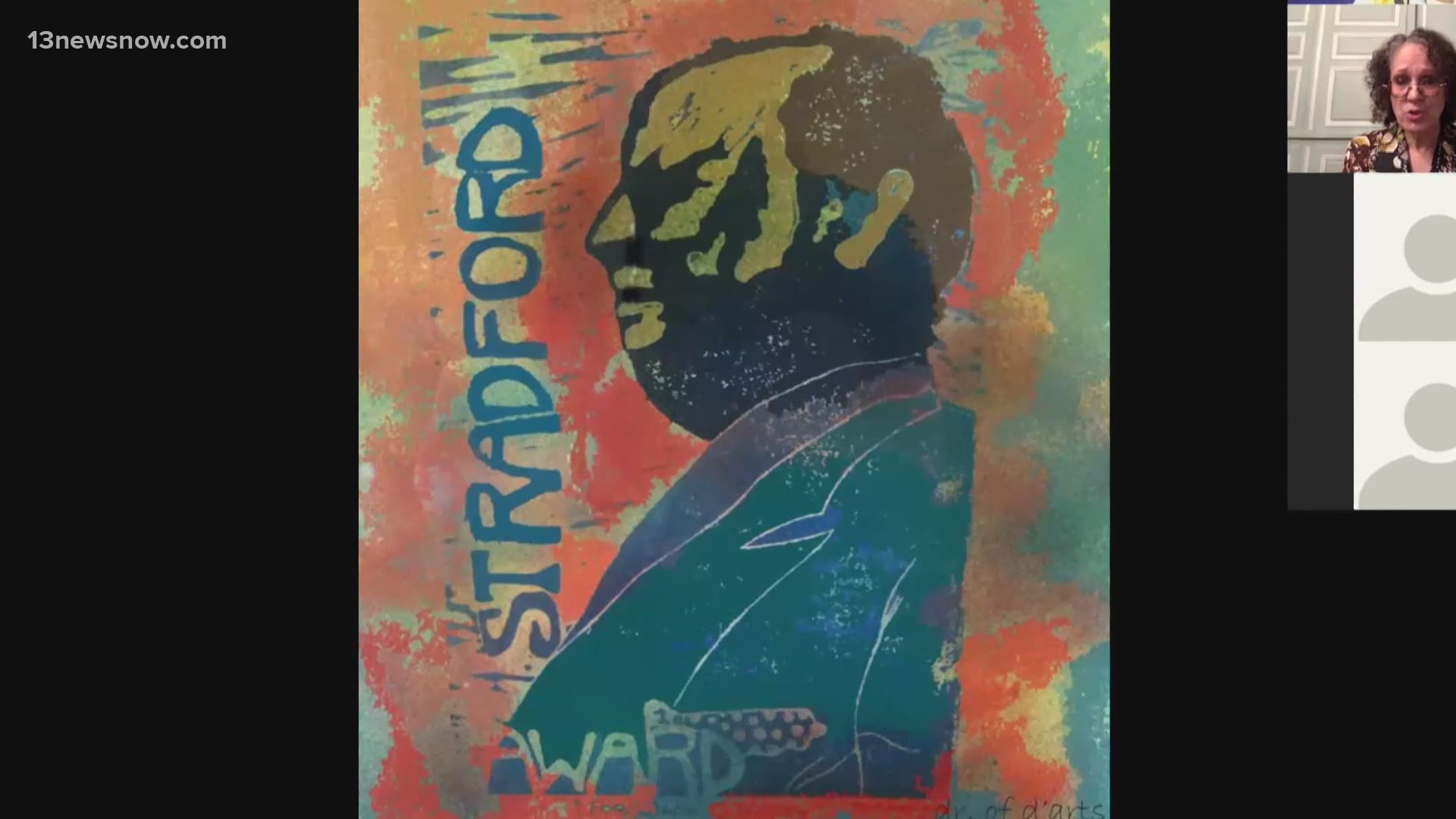

Dr. Leslee Stradford uses her art to teach.

"It's a way of creating images that would tell historical fact in a way that was easy to understand through images, as opposed to asking someone to read a document," she said.

This particular topic, however, didn't make it onto most documents anyway.

"The people writing texts are not including African-Americans in them," Stradford explained, saying she's had people from Tulsa, Oklahoma tell her they'd never heard this story.

Especially shocking considering the event today's virtual seminar: The Tulsa race massacre of 1921. A thriving, 11,000-person Black community was attacked and burned to the ground by the neighboring white community over the course of two days.

Stradford said at least part of the motivation was jealousy.

"They prospered, they had a bus route, a taxi cab service, funeral homes, barbershops, grocery stores. They had everything the white community had, and they used that power to support each other."

In the midst of this flourishing community, a teenage black shoe shiner startled a 17-year-old white elevator operator. She claimed he tried to attack her and the shoe shiner was arrested. Rumors swirled of a possible lynching, with the Ku Klux Klan soliciting the sheriff for permission to do just that. Seventy-five members of the Black community went to the courthouse to protect the boy from lynching. A member of the group was confronted by a white man...

"He said, 'Where do you think you're going, expletive?' He replied, 'I'm going to protect this man.' He said, 'Protect him from what?' and he pulls out his gun and he shoots him, then all hell broke loose," Stradford describes the first shots being fired.

When the dust had settled, the Black community had been burned to the ground by armed members of the white community, eventually supported by a late-arriving military. The town was gone, and the surviving members of the community scattered.

Dr. Stradford uses her images to convey what happened in this once-thriving community, and while her audience is educated, she finds healing. Stradford's great grandfather lived in Tulsa in 1921. He was the owner of a hotel that was used as a safe haven for traveling African-Americans. He escaped to Chicago after the massacre, and his hotel was burned down along with the rest of the buildings in town.

"Where my great grandfather's hotel was, is now a highway. They built a highway right through his hotel," Stradford said, sounding at once dismayed and incredulous at describing what now stands where her family's beacon of comfort once stood.

While his hotel may never be rebuilt, Dr. Stradford works to rebuild his and thousands of others' stories, one piece of art at a time.