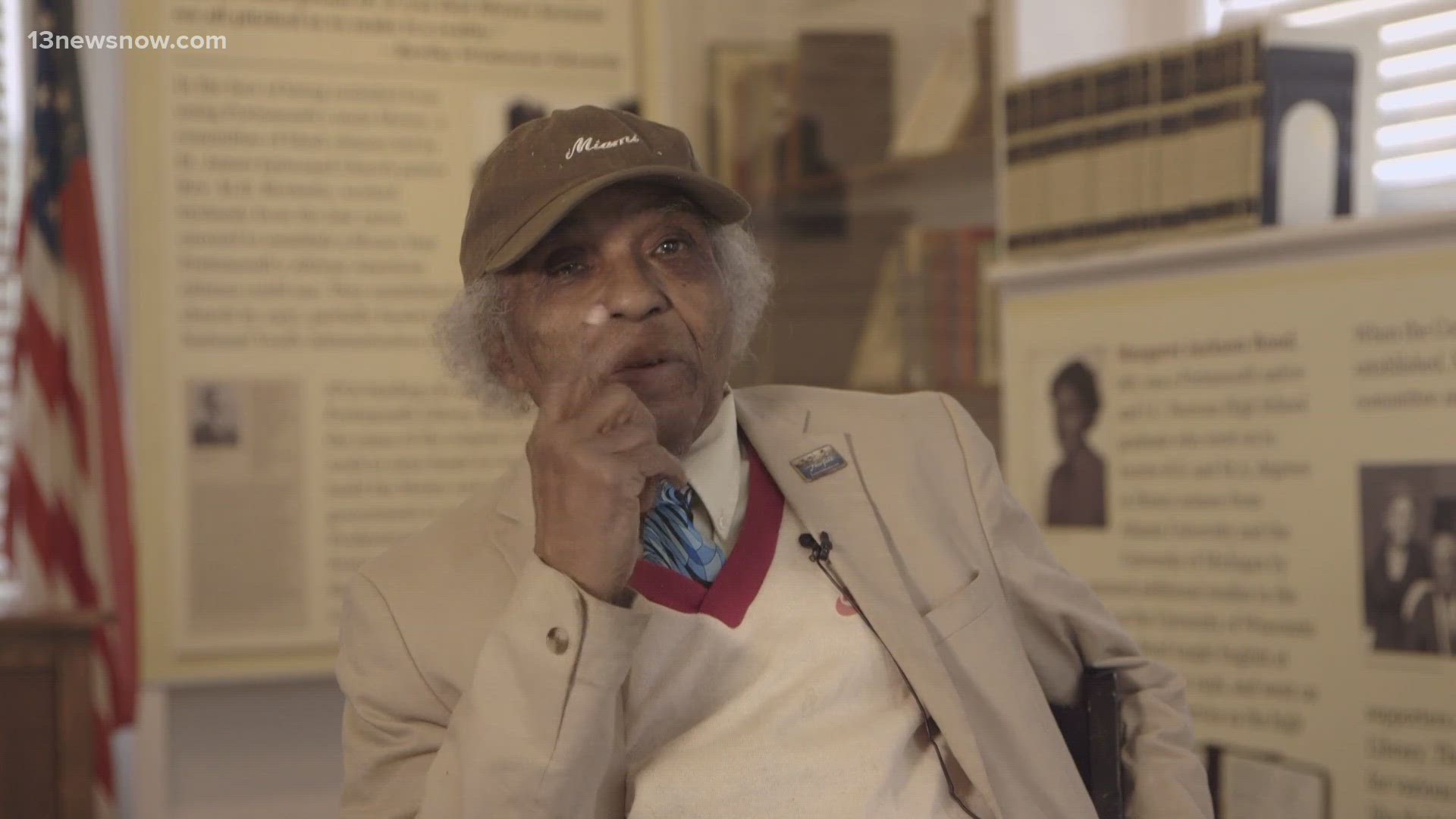

PORTSMOUTH, Va. — Ed Joyner walked into the museum for the African American Historical Society of Portsmouth with a smile. There's something about telling stories that seems to lighten his spirit and he has a lot of stories to share.

Born shortly before World War II, Joyner has been through a lot of history young people now read about in their books. However, he felt that he really found his voice during the civil rights era, when he went to college in Baltimore and experienced an entirely new world outside of Virginia.

"Well, they were very exciting times. I started quite young," Joyner said with a smile.

Fighting for civil rights from a young age

Joyner's first experience was during his freshman year in college when he marched in a segregated shopping center located in the heart of Baltimore.

"During our four years, we still didn't succeed with the integration, but we put a lot of pressure on the succeeding students in the following years. Eventually, they were able to break the segregation down," Joyner said. "I also had the opportunity to go on the first march to Washington."

Joyner grew up in a segregated neighborhood of Portsmouth and he really only knew that neighborhood until he left for college. In addition to marching at segregated shopping centers, Joyner said he also attended a commencement as a band member where he stood in a pit in front of a stage where Martin Luther King Jr. spoke to a crowd of people as a commencement speaker.

"That was the year he had just won the Nobel Peace Prize," Joyner said. "It was just quite an experience and I never forgot it."

Those inspiring moments are the ones that kept Joyner through the darker times. At the age of 20, Joyner said he and a bus full of people stopped at the bus station and wanted to get something to eat.

"They had these White Castle hamburgers, during the time that you could get 10 for a dollar," Joyner burst out in laughter. "But you weren't supposed to go to the front to get the White Castle hamburgers. You had to go to the back. There were like 30 or 40 of us, all Black people, no white people were there. When I told the police that I was from Virginia, they said, 'you should have known better.'"

This time is when reality settled and weighed heavy on Joyner, but it didn't stop him.

He even joined the Freedom Riders group on the bus down to Nashville, Tennessee to protest segregation, but he was not able to stay on the bus, which had a route down to Birmingham, Alabama, because he had to work that Monday morning. So, Joyner skipped out on the trip, which was on the same bus that was attacked by a white mob and burned in May 1961.

These times of historical racism Joyner physically and mentally marched through are now at the center of controversies pushed by state leaders across the country.

Teaching of Black history faces political challenges nationwide

Over the past few years, the question of how certain pieces and concepts of history should be taught in the classroom has been challenged by state officials across the nation.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, for example, has been grabbing national headlines over his latest bills regarding lessons about slavery in the classroom. That includes the "Stop W.O.K.E. Act," which prohibits classroom lessons that could prompt students to feel discomfort about a historical event because of their race, sex or national origin.

DeSantis also received a swell of backlash over his language surrounding how Black history should be discussed in schools. According to the Associated Press, the governor required Florida’s teachers to instruct middle-school students that enslaved people “developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.”

In Virginia, the first thing Gov. Glenn Youngkin signed when he took office in 2022 was an executive order designed to push Critical Race Theory (CRT) out of the school systems. Critical Race Theory is a concept that evaluates systems of racism in America and how they’ve evolved and been perpetuated.

Youngkin ordered the Virginia Department of Education to conduct a review while his administration created a tip line for parents to use if they notice teachers using critical race theory or other teaching material in their lessons that some believe to be divisive.

"If it's part of the lesson plan, then teach it," Joyner said. "If it's not part of the lesson plan, don't get into your personal types of opinions. When it comes to race and religions, you're going to offend a lot of people that are not part of that particular program."

Joyner believes learning about racism in history and how to address it in our modern day is essential. He said keeping it out of the classroom would prevent students from learning about the big picture of how systemic racism played a role and still plays a role in America.

"Especially for the young people because if they don't know where they came from, they're not going to know where they're going," Joyner said. "And that's great for not just African Americans, but for all people. Constantly letting people know how things used to be and hopefully, we never have another day like that again."

Youngkin's administration eventually shut down the tip line, saying the office did not receive enough messages from parents to utilize the resource.