13News Now Investigates: New DNA technology police say helps crack cases

Advances in DNA evidence collection and testing are giving law enforcement agencies edges when it comes to their investigations.

NORFOLK, Va. (WVEC) -- Police are using new technology to better collect DNA and use profiles differently, finding that the advances have the ability to crack cases once considered cold.

The advances are not the stuff of science fiction, but of actual law enforcement cases, including some right here in Hampton Roads.

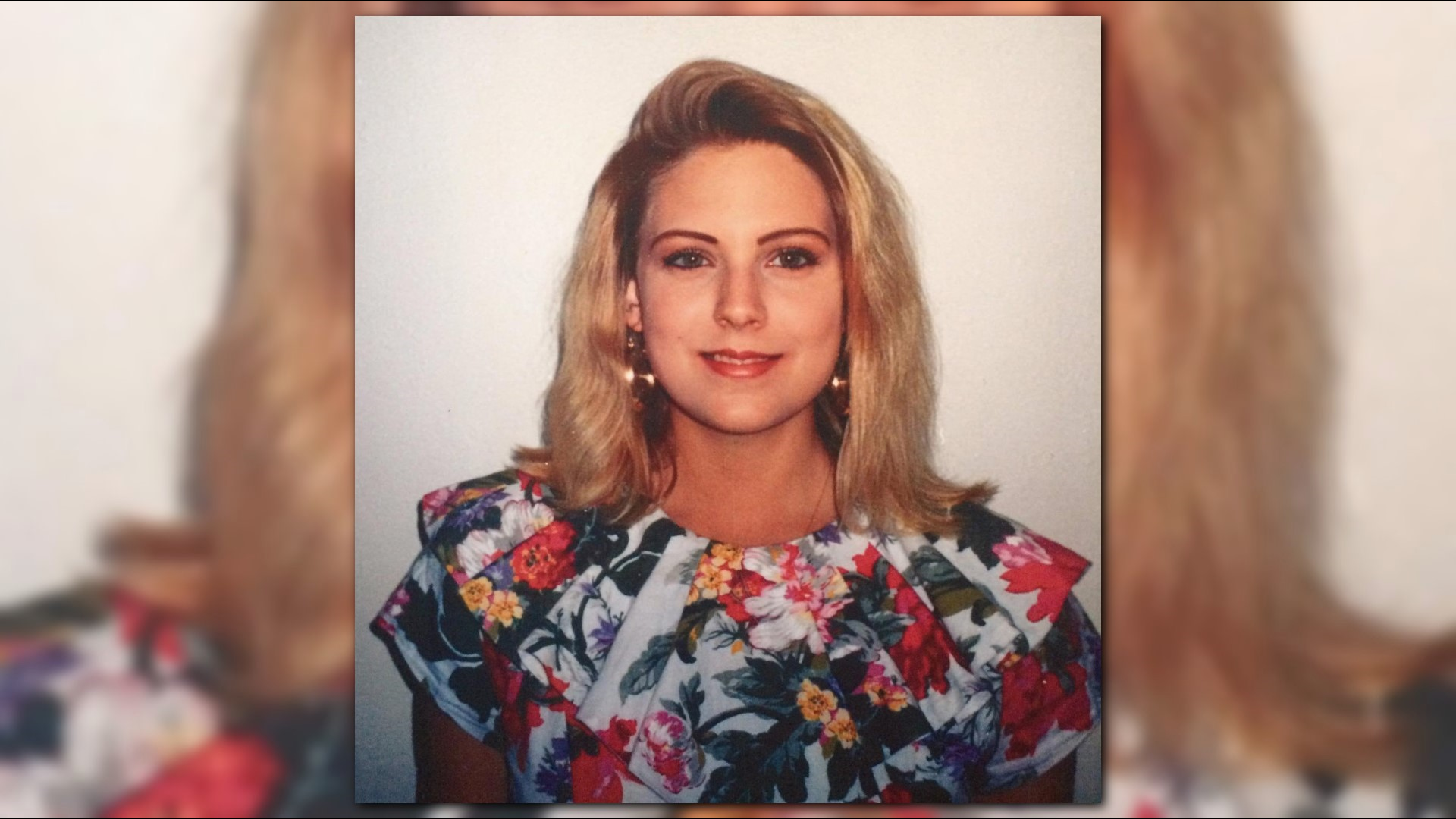

As an example, investigators from Isle of Wight County told 13News Now the still-unsolved murder of Carrie Singer in 2004 may be more solvable than ever thought.

Technological developments have allowed law enforcement officers to gather new DNA samples and use those samples to construct a blueprint of Singer's killer.

A mother’s plea, a detective’s mission

A "true friend," is how Patty Lord describes the oldest of her three children.

"Carrie would light up a room when she walked in,” Patty recalled.

In 2004, Carrie Singer moved to Hampton Roads.

“She enjoyed life to the fullest,” Patty said.

Shortly after, Patty got the news no mother ever wants to hear.

“It was unreal,” she remembered. “Nothing seemed real at that moment.”

On July 1, 2004, a farmer found Carrie's body at the edge of a field near Morgart's Beach. Investigators with the Isle of Wight Sheriff's Office cordoned off a crime scene to collect evidence, but the case ended up going cold.

After years of dead ends, the sheriff's office reopened Carrie's file in 2012.

“This case has definitely been a rollercoaster full of emotions,” said Lt. Tommy Potter, who is now the chief investigator. “We can't talk to our victim, obviously it's a homicide case. We don't have a lot of circle of friends and acquaintances to talk to. All we have is physical evidence and we need something to give us that break in that case.”

It came when the team learned about a private lab in Florida using something called an "M-Vac." Up to this point, detectives had to use their best judgment to guess where on a piece of evidence a suspect may have touched or left DNA and then have state lab test that specific area. But M-Vac is like a powerful vacuum for DNA.

“Instead of having to pinpoint the most likely location, they are able to process the entire item,” Potter described. “So, it greatly enhances the forensic scientist's ability to extract a profile.”

After 13 years, M-Vac led to the discovery of a new profile on the evidence in Carrie's case.

“We think the profile that we got from 2017 is the profile of the person responsible for Carrie's death,” Potter enthused.

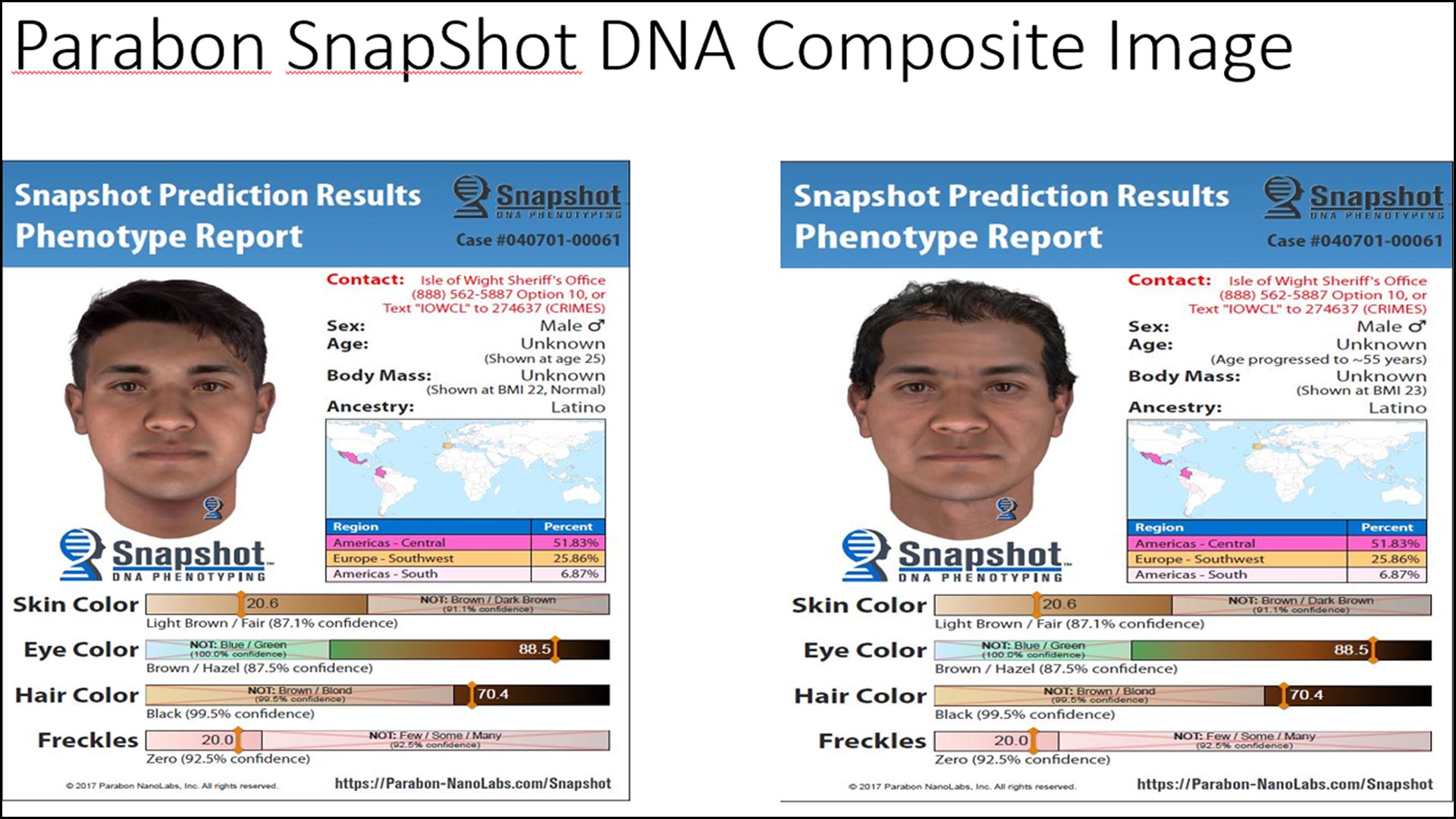

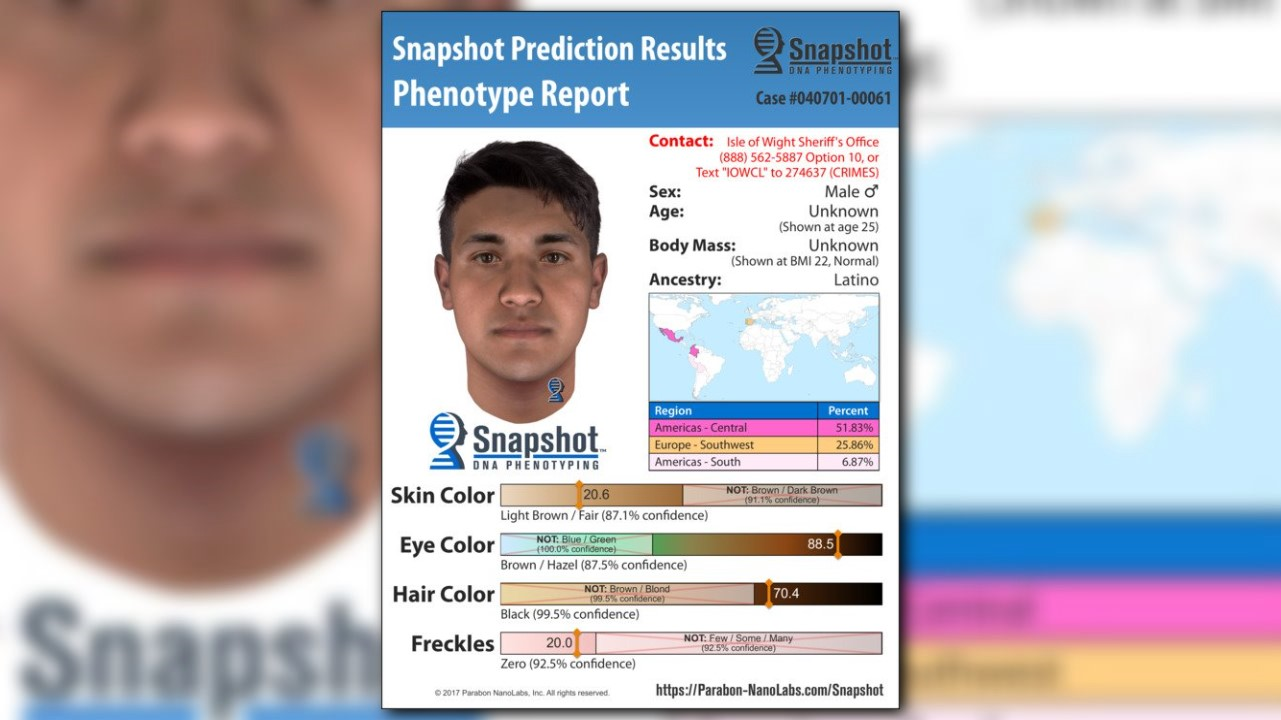

Authorities then utilized another technology which did not exist back in 2004. Parabon Snapshot used DNA Phenotyping to come up with a composite of a possible suspect in this case. The science predicts physical appearance and ancestry based on a DNA sample.

Potter said this was a game-changer. In the past, any tips about suspects had been about white men, black men and a friendship Carrie had started with a female.

“We have spent 13 years concentrating on those groups of people and in one test, we now know that in our case we are looking for a male who has a Latino or a Hispanic background,” he explained. “It's kind of like a compass. Parabon has pointed us in this direction and says this is the direction you need to go.”

Patty Lord hopes someone will see the composite and know something about her daughter's case.

“I just hope that through my lifetime that there will be earthly justice for Carrie,” she added.

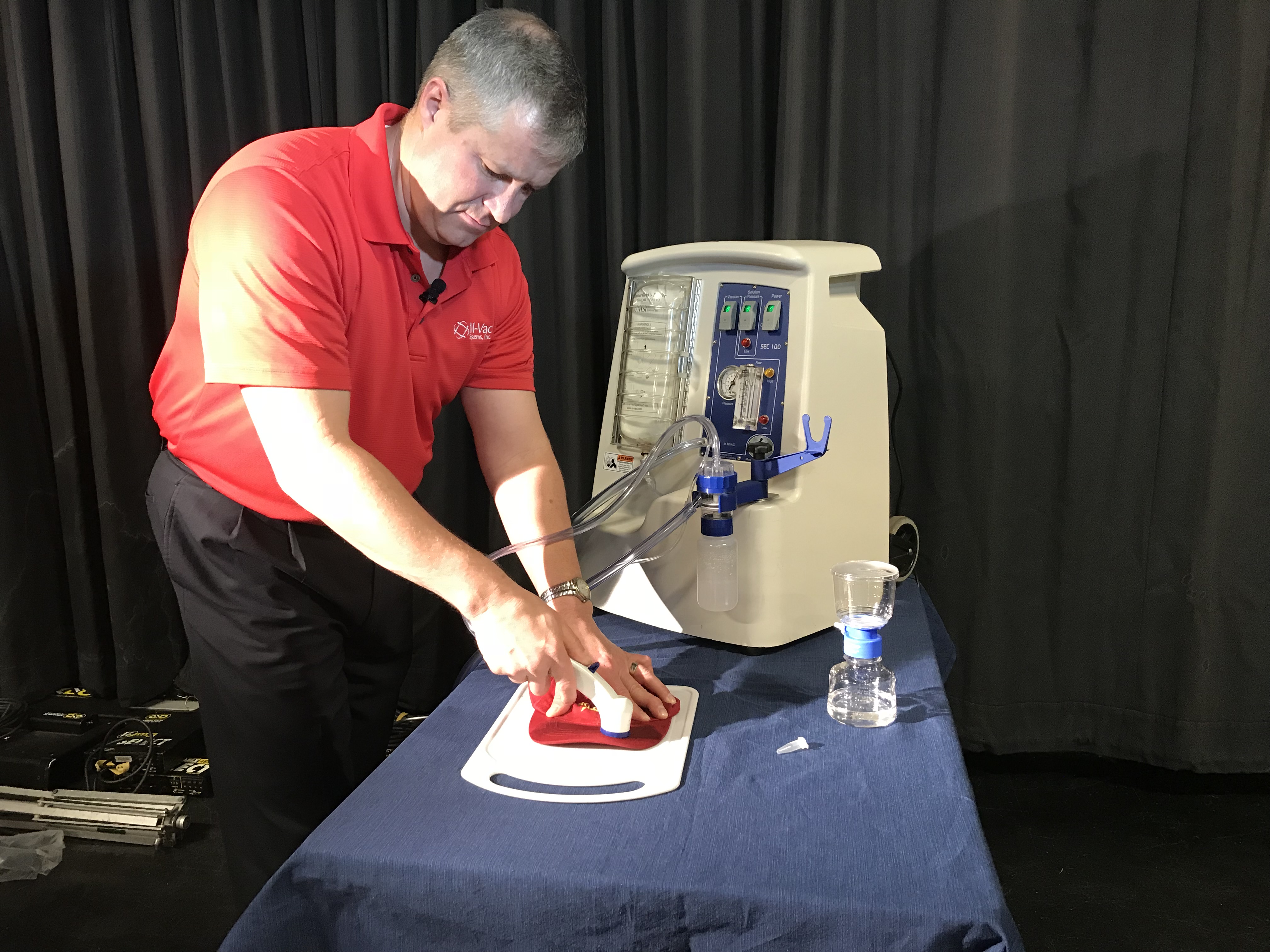

The M-Vac

A lot of times when we're talking about evidence collection, you'll see a swab that's like a large Q-tip.

The swabs are great if you have an obvious sample to collect or you know where someone has touched. But they're less helpful if you needed to collect possible DNA from a large area, or if there's a minute sample that might be buried in a porous material or fiber, or if you needed to swab a rough surface, like a brick, the swab could come apart.

That's where the M-Vac can now come in. Police departments are using it to obtain evidence where traditional methods have failed.

Items collected from the crime scene of Carrie Singer’s murder led investigators nowhere. That is, until now: the sheriff's office had evidence re-examined using the M-Vac.

“For 13 years, these items had been sitting in our evidence room and there was this profile that we were able to -- utilizing new technology -- were able to extract, develop a profile,” Isle of Wight Sheriff’s Office Lt. Tommy Potter described.

Detectives said using that piece of equipment has changed the course of Carrie's case. But Isle of Wight investigators had to go all the way to Florida to utilize the M-Vac. No police departments in Virginia have one.

M-Vac Systems President Jared Bradley is trying to change that. He recently met with law enforcement throughout Hampton Roads.

The M-Vac works like a high-powered carpet cleaner. When you have a large mess buried into your floor, the carpet cleaner sprays a cleaning solution down, and then sucks up the stain or whatever is on the carpet.

“The M-Vac system is trying to get DNA, whether it be blood, saliva or even epithelial cells, which we call 'touch DNA,'” Bradley said. “It is trying to extract that out of the surface.”

This sampling head sprays down a solution on the inside rim and vacuums up that solution and evidence along the outside rim.

That solution containing the evidence is collected in a bottle, then poured into a filter device. Bradley told 13News Now that process traps any DNA on the filter.

The M-Vac has been used in cases to get DNA from rocks, cement, clothing and larger surfaces, including the trunk of a car. Right now, only 35 police departments have one.

The system starts around $35,000, but Bradley believes the cost of the invention isn't necessarily the issue for law enforcement.

“They are extremely hesitant to use a piece of equipment that's not tried and true,” Bradley explained. “They want to make sure if they use it on their case, then of course, they're going to get the results they want.”

While Bradley makes his pitch to law enforcement in Newport News, Virginia Beach and Isle of Wight, he hopes the recent results, like we've seen in the Singer case, speak for themselves.

“Behind every case is a victim,” he lamented. “To know that we're helping the investigators move those cases forward, be able to help those victims receive justice and the families to get closure, that's a wonderful feeling.”

Parabon Snapshot

A company in Northern Virginia is using DNA samples from local cases to create composite profiles recently released by detectives in cases they haven't been able to solve.

Investigators said the science created by Parabon Nanolabs may hold the keys to solving some gruesome crimes.

DNA has long been used to help detectives identify suspects or tie them to crime scenes, but if there's no match or "hit" in a database, that profile couldn't tell investigators much of anything else. Now, phenotyping has changed everything.

“Snapshot is just an entirely new way to think about forensic DNA,” Dr. Ellen Greytak, with Parabon Nanolabs, said.

Think of your DNA as a blueprint for what you look like. Biomarkers produce the wide range of appearances among people. They're why one person has brown hair and another has a narrow, long face.

“We know the DNA codes for the color of your eyes, the shape of your face, the color of your hair and we're just reading that information out,” Greytak described.

So, when law enforcement -- like we've seen in both Isle of Wight and Virginia Beach -- bring Parabon a DNA profile taken from evidence, scientists can put the information into a computer algorithm to predict the physical traits. They focus on those that are externally visible and entirely genetic.

The genetic information is given a numerical value, which falls upon a scale of options. When the data corresponding to face shapes is entered into the system, a generic picture morphs into a specific shape.

“We have X, Y and Z, so that's width, height and depth, and in each face red is an increase and blue is a decrease,” Greytak illustrated.

Everything is combined into a composite profile report given to police departments. Each prediction has a confidence level.

“We emphasize that this is not a photograph,” Greytak relayed.

In investigations, Greytak explained detectives can use the composite to prioritize the suspects on their list.

“It's not going to tell you it's this one individual, but it can tell you it's a small subset of those individuals and what we really focus on is who is it not,” Greytak added. “We're never saying, 'Take this person off the suspect list.' We're saying they're less likely to match.”

So far, the science has been used in about 150 cases across the country, including one dating back 45 years. Analysis of a single DNA sample costs $3,600.

In Hampton Roads, police are now hoping to use Snapshot to crack cases.

“Just to realize that there is technology that exists today that did not exist in 2004, and there'll be technology that exists tomorrow and next week and next month that did not exist today,” Lt. Tommy Potter said. “And each advancement in technology is something that law enforcement can use that can bring us one step closer to solving.”

Critics voice concern over using new technology

The American Civil Liberties Union of Virginia is urging caution for local police departments using new DNA technology, like Parabon Snapshot.

The ACLU said it praises the police for wanting to do everything possible to close cases and bring victims and families justice, but, for them, this new technology is not without concern.

Officials have concerns about the system that analyzes DNA from a crime scene to create a composite of what a suspect might look like.

“We're asking that local law enforcement, state law enforcement just draw the line and not use the technology,” said ACLU Director of Strategic Communications Bill Farrer.

He believes more work needs to be done to prove the system valid and worries releasing composites to the public could lead to innocent people being unjustifiably suspected of crimes and forced to defend themselves.

“The result is that most of the profiles that come out of phenotyping are very, very generic individuals,” Farrer described. “It could be almost anybody.”

Snapshot focuses on traits that are externally visible and entirely genetic, including eye and hair color, skin tone, ancestry and face shape. Farrer thinks those won't always be helpful.

“When police put out a bulletin and say, 'We're looking for this person,’ the kind of things that most people look to identify that person are things like height, weight, does the person have facial hair, things like that,” Farrer illustrated. “Phenotyping doesn't identify any of that.”

We asked Parabon's Dr. Ellen Greytak to respond to the criticism.

“If a witness describes someone and gives the police that description and they use that to try and find the person, is that profiling?” Greytak asked. “No, it's just telling the facts. We are producing objective predictions that are based on science.”

She explained they are specific with police departments that the composite is not a photograph.

Isle of Wight Lt. Tommy Potter, who is using Snapshot to try to solve the 2004 murder of Carrie Singer, sees the possible concern.

“I would say that if law enforcement was using Snapshot, that composite, alone to make an arrest, then they have a valid point,” he responded.

But he wanted critics to understand for police, this is just another tool in their toolbelt.

“It goes hand-in-hand with going out and interviewing witnesses,” Potter described. “It goes hand-in-hand with going out processing all the evidence at a crime scene. It just pushes us one step closer to getting to the probable cause.”

Still, if police departments continue to put out the composites, the ACLU hopes the public will keep this in mind:

“If they see that sketch and think that it could look like someone they have seen or known, to think twice before reporting that person to police,” Farrer advised. “Just because it might look like that person, doesn't mean that person has any association with that crime whatsoever."