'He couldn’t handle being here' | After the earthquake, Puerto Ricans struggle to rebuild

The strongest earthquake in a century hit the island on Jan. 7, but hundreds of aftershocks have been felt since, shaking its people. Here are some of their stories.

At 2:24 a.m. local time on Jan. 7, a magnitude 6.4 earthquake struck the southwest region of Puerto Rico. A state of emergency was declared as thousands of people ran into the streets confused and searching for safety.

It was the strongest quake to hit the island in a century.

WUSA9 sent reporter Ariane Datil to the island to document the aftermath of the earthquake. This is her account of the trip.

Welcome to the Island

I’m Ariane Datil. Yo soy Boricua.

I was born in Philadelphia and work in D.C., but my family is from Puerto Rico. I have aunts, uncles and cousins still living there. They all live in the northeast corner of the island -- an area that faced little-to-no damage after the quake. Thankfully they were safe -- their homes secure.

Feeling safe is not a reality for thousands of Puerto Ricans who live on the opposite corner of the island. Near Guanica, Guayanilla, Yauco and Ponce, thousands of small earthquakes have been shaking the area since Dec. 28.

The quakes and aftershocks damaged more than 800 homes and businesses, displacing more than 8,000 people.

"What happened in Guanica is a tragedy," a woman, named Ruth, told me. "So many families lost their homes. The hardest thing to see is people sleeping in the street, sleeping in parks (children and senior citizens). That is what is hardest to see."

I’ve covered stories about Puerto Rico as much as I could from Washington -- watching protesters gather in front of the Department of Housing and Urban Development for funding still owed from Hurricane Maria, Skyping with Jose Andres’ World Central Kitchen organization to see how food was being distributed to displaced families, even attending local fundraisers aimed at sending resources directly to people in Guanica at ground zero.

While those stories helped show people on the mainland a small slice of the aftermath of the earthquakes, I knew that in order to truly see what my boricuas were doing, I needed to go there myself.

Con mis propio ojos -- With my own eyes.

My plane landed in San Juan around 5 a.m. on Jan. 18.

It was a very humid morning. Normally when I go to Puerto Rico, I’m going to see family, so I’ll have on vacation clothes and flip flops, but not today. I was wearing the same outfit I wore to work the day before: A light pink, cheetah print dress shirt and slacks. I was already sweating.

By the time I made it to my rental car, the sun was just starting to rise.

As I drove toward Yauco in the southwest corner of the island, I saw dozens of cars packed with pillows and supplies lined up along the side of the highway, as though people had stuffed them to the brim with everything they could find.

I knew people were staying in cars and tents in front of their homes because they were too afraid to be inside, but was that fear so intense that they now only felt safe sleeping in their cars on the side of the highway?

I slowed the car to a crawl, pulling over on a dirt road to find out.

What I actually saw were dozens and dozens of church groups from other parts of the island. They came in caravans stocked with supplies to help their hermanos in the south.

Their cars were packed full of supplies, including socks, underwear, sheets, food, diapers, etc. Some of the items were gathered from their neighborhood. Others were given to them after Hurricane Maria -- and kept in preparation for the next hurricane season.

They didn’t see this coming.

A report by the U.S. Geological Survey shows people in the southwest corner of Puerto Rico may feel shaking from magnitude 3.0 aftershocks on a daily basis for the next two to six months.

Before going to Puerto Rico for this trip, I had never experienced an earthquake. During dinner on the first night, that all changed.

I picked this beach-shack-style restaurant because it had a fabulous patio with draped lights and a great view of the ocean. About three-quarters of the way through my mamposteao y mofongo con camarones, the structure started shaking, swaying from side-to-side. I looked down to the lower deck to see if anyone else felt the tremors. Claro que si.

Everything seemed to stop for a second, perhaps 5 seconds -- that’s how long the shaking lasted. But those seconds felt like lifetimes to me. I didn’t move. I probably should have gone downstairs immediately, but I just sat there. Shocked. In the blink of an eye, everyone was back to what they were doing before the quake.

Experience the earthquake aftershock in the video below:

A few minutes later, a waiter came upstairs to me, seemingly unfazed, holding a pitcher of water. As he filled up my glass, he told me that yes, he felt it. He'd felt about six earthquakes every night for the last week or so. At night, he said, was when they really picked up.

Because I was moving around so much, I didn't always feel the tremors like I did at dinner that night. But every day after that I felt at least one tremor ranging from a magnitude 2.0 to a 4.8.

While the frequency of aftershocks is expected to decline, the U.S. Geological Survey reported that Puerto Rico may experience tremors from that one earthquake on a weekly basis for the next decade.

For Puerto Ricans, these constant quakes are now reality -- one that is taking a toll of people’s peace of mind.

But what happens after the shocks are over? What type of impact do these earthquakes have on not just physical properties, but also boricuas' – Puerto Ricans' – mental health?

El Salud Mental | Mental Health

Before I booked my trip to the island, I spoke to so many people all over Puerto Rico. I asked them how these earthquakes compared to Hurricane Maria, another devastating catastrophe. Everyone I spoke with told me a variation of the same thing: At least Maria stopped. This doesn’t stop. They don’t feel safe in their own homes.

Dr. Vanessa Torres is a D.C.-based psychiatrist who was born in Puerto Rico. I met with her back in D.C. at a protest where she was fighting for money owed to Puerto Rico from Hurricane Maria.

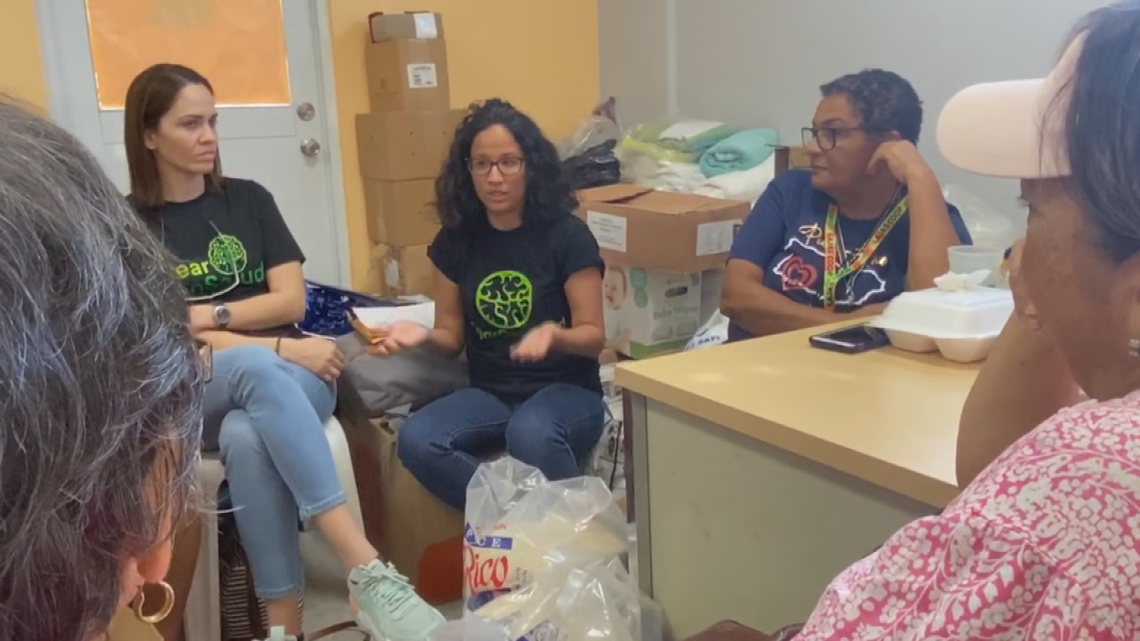

She was traveling to Puerto Rico in a few days to work with community leaders and relief workers, all of whom had been working nonstop since that historic Jan. 7 quake.

Torres was working through an organization, called Brigadas Salubristas, where she planned to do on-site mental health consultations for people impacted by the earthquakes on the island. She also planned to give more structured guidance to community leaders and relief workers, which she called resiliency training.

People who give so much of themselves to others need people like Torres to pour back into them and teach them healthy ways to cope.

"I feel alone. I feel really alone, like I don't matter to anyone."

I spent an afternoon at a shelter in Lajas, where more than 800 people were staying. I sat down with some of those families at the shelter who shared with me the gravity of their situation. Many, thankfully, hadn’t lost their homes completely. But they were still frightened about the prospect of going back.

There were so many children at that shelter. When I got there, the kids were getting their faces painted and playing with bubbles. That weekend was La Fiesta de San Sebastian – a massive, multi-day festival in San Juan to celebrate the end of the holiday season.

Yes, in Puerto Rico the holidays aren’t over until the middle of January. We're geniuses, I know.

Maybe that explains why I can’t seem to take my Christmas tree down as soon as some of my neighbors -- it’s in my blood to keep the festivities going.

And, I. Cannot. Resist. Bubbles.

At one of the shelters we visited, kids were having fun despite the circumstances, filling the air with hundreds of bubbles. So obviously, I went over to play with them. We had a blast. The kids figured out that if they put the bubble stick in front of a fan the bubbles would dance across the room. There were bubbles everywhere.

It was incredible to see and experience. These people likely lost their homes, or at least were too scared to stay in their homes, and yet these children were able to smile thanks to some soap and water. My heart was exploding.

Before the earthquake, one of the relief workers worked at a cafeteria. Because many of the buildings and businesses around the cafeteria were destroyed in the earthquakes, she lost her job.

Another relief worker, named Jessica, had been at the shelter since day one. She shared with the group her strategy for getting through the tough times.

When I asked why the earthquakes were causing great mental health concerns greater than Hurricane Maria, Torres explained, "It's the uncertainty and the shift in dynamics of the disaster."

"Before, you would make sure to secure the windows and stay inside, and now this is completely shifted," she said. "Now you have to leave and you're outside.”

Daily tasks are made infinitely more stressful because of the unknown.

If I sleep in my house, will it come crashing down on me?

If my grandmother takes a shower right now, will she slip and fall because the house starts to shake?

People shared all sorts of worries with me. They also shared what keeps them going.

La Fe | Faith

Sunday was a day that will be cemented in my memory forever.

I was driving through downtown Yauco when I noticed people gathering in a park, holding instruments and speakers, sounding like they were doing a mic check. I quickly turned my car down the street to ask them what they were setting up for.

"Church," they said.

I asked my photographer to hop out of the car so we didn’t miss anything while I found a place to park. I drove about a block-and-a-half north and stumbled upon another large group of people gathered in a plaza. This time it was abundantly clear what they were doing. This was a mass.

A beautiful church was at the far end of the plaza. A tent was set up outside with an altar. The choir was gathering behind tuning their instruments.

I grew up Catholic, so I know very well that little stands between a devout getting to mass, not even an earthquake.

A woman in the growing crowd, wearing a fabulous pair of glasses, caught my eye. Her name was Annie Santiago. I sat down beside her and asked her why mass was being held outside today.

"Estamos afuera porque la iglesia sufrio una problemita en la campana arriba y pues tiene miedo de que puede hacer dano," she said. ("We are outside because the church suffered damage to the bell above, and we are worried it will cause harm.")

Like I said before: Nothing keeps a devout Catholic from mass.

Santiago's church is called Iglesia de Santisimos Rosario de Yauco.

The earthquakes damaged the choir and sides of the church. From where I was sitting, the church looked pretty normal. I didn’t see any obvious structural damage on the outside, nor piles of rubble on the ground around its base. I did notice, however, red tape strung between two trash cans in front of the church.

On the gates that separated the church entrance from the road hung a white sign that listed the times for mass. At the bottom of the sign it asked people to bring a seat and an umbrella and join them in the Plaza Fernando Pacheco just across the street.

I walked back to the park and stayed for mass. It was beautiful. The singing, the prayers, the ritual of it all. It was comforting.

In the midst of a reality that offered very little comfort at the time, I understood completely why it was so important for those parishioners to come together for mass in whatever way they could.

Below, WUSA9's Ariane Datil reflects on faith, church, and community:

After mass, I spoke to the priest about the extent of the damage done to not only the church, but the cloisters where he lived. He told me what it would take for the doors of Iglesia de Santisimos Rosario de Yauco to reopen.

Below, a Puerto Rican priest explains the damage his church suffered in Yauco:

La Communidad | The Community

Lynette is a professor of radiology at National University College in Ponce. She’s also a community leader in Barina. It’s a town on the hillside of Yauco in the southwest part of the island.

Community leaders are invaluable in the face of a disaster. Lynette is responsible for knowing the needs of her community: How many people are ill and can’t get out of bed? Who is pregnant? Who needs more emotional support? -- Questions she can answer.

On the first day of the trip, I watched her work tirelessly with Torres and the Brigadas Salubristas from early in the morning until just before sunset, when she dropped me off at my car.

Lynette guided the group from neighborhood to neighborhood, house to house, checking in on families and facilitating communication between campsites so that resources could be distributed to those that needed them most.

She did all of that while her family was sleeping in cars at a community campsite in their neighborhood.

Their camp -- Campamento Solidaridad (Camp Solidarity) -- was the first one I visited. It was a really hot day and the camp was packed. From a distance, it looked like the beginnings of a neighborhood get together. Since it was the weekend, everyone was "home."

People were passing out food and supplies while others were sitting in folding chairs, talking or passing the time. The tents were the only place to escape the sun.

Camp Solidaridad was home to 50-70 people from the community. A community comprised of mostly teachers, retirees and middle-class families. During the day, people who could go to work did. Those whose companies couldn’t reopen or who are retired tried to find shade under the blue tents and make themselves helpful to others.

Lynette’s school reopened just a few weeks after the big quake. She had been working for about three days by the time we met her.

For people who were fortunate to still have a job to go back to, work was a reprieve from the chaos of home life. At work, most of them had air-conditioning, running water and automatic bathroom facilities. Camp life was much different.

Porta-potties, group meals, sleeping in cars and finding creative ways to shower were now a reality for thousands of people.

Lynette, in some ways, seemed more fortunate than others. Her home didn’t sustain much damage. A blessing that she attributed to her ritual of rubbing holy oil in every corner of the house after the first quake hit.

Her home was deemed structurally sound by an engineer who came through the neighborhood, but Lynette, like many others who received the same assessment, was too afraid to stay in her home.

Every day after work, she'd stop at home for no more than 10 minutes. In that time, she'd shower and grab clothes for the next day then immediately head to the camp. And that’s where she'd stay until the next morning when she got up at 6 a.m. to get ready for work.

I was curious about what her workday morning routine looked like, so on Monday, I went to the camp before the sun came up so that I could be there with her.

People started waking up around 6:30 a.m. Slowly, car doors were opened one by one as people got out to stretch their legs and wipe their sleep away.

Her neighbors that needed to get to work changed clothes quickly and were on their way, while others started to cook breakfast.

Lynette explained that every night her ankles would swell and she would awaken in pain. She told me this as she led me to her husband and neighbors who were already gathering in the blue tent.

At Camp Solidarity, breakfast is a community event. While one woman was cooking harina de maiz (cornmeal) -- a Puerto Rican staple -- in a pot on the grill, other camp members were organizing supplies or just catching up.

Lynette’s husband told me that the one good thing to come from these earthquakes was the opportunity to connect with his neighbors.

"The good thing about it is that most of us have lived here for a while," he said. "We usually say hellos while we're driving by. We don't have time together to share and to enjoy each other's company."

They all worked together like a well-oiled machine. Camp was organized and food was plentiful. And while everyone was very friendly and pleasant, you could see on their faces they had been through enough. The toll of sleeping in their cars and not being in their own homes was weighing on them.

Pit Stop

Empandillas, or pastelillos as I grew up calling them, are another Puerto Rican staple. Flour pockets filled with your choice of ground beef, pulled chicken, shrimp, crab, pizza… the options are endless. They're kind of like Pringles… you definitely can't just have one.

On the way to my next location, I stopped at an empanadilla stand on the side of the road near Lajas.

“Una de carne y una de res, por favor,” I said to the woman behind the counter.

The next few minutes are a bit of a blur. Puerto Rican food has a way of taking you out of reality and into a better place. I forgot that I was sweating through my clothes and definitely wore the wrong shoes that day. I was enjoying the memories of eating pastellilos at my abuela’s house in Vega Baja when I was little. Picking mangos off the tree in her backyard and not worrying about the mosquitos biting every visible inch of skin on my body.

Los Daños | The Damage Subtitle here

On Tuesday, I spent the day at Camp Biquingo. A much different camp from Lynette’s. This one is home to just one family: The Pachechos.

Mike Pachecho, his three children, their mother, his mother-in-law, sister-in-law, son-in-law, grandson and some cousins all live there. Mike constructed them a makeshift-home made from blue tarps and donated wood. It was truly impressive. There were bedrooms, a living room outfitted with a TV, radio and fan (for the mosquitoes), a fully functioning kitchen and an outdoor shower.

WATCH: See a tour of the inside of Camp Biquingo

“If he wasn’t here, I don’t know what would happen to us here. I think God was the one who sent him because something was going to happen.” – Haydee Santos (Abuela)

The two homes they lived in before the earthquakes sat just across the street from their makeshift home. When I met the Pachecos, a structural engineer had not come by to assess whether the houses were uninhabitable. By my untrained eye alone, the blue house seemed beyond repair.

I invited Kit Miyamoto, structural engineer and CEO of the Miyamoto Engineering Firm, to come take a look at the two houses. With him was Sabine Kast, a disaster recovery specialist from Miyamoto, and Mariela, who works with DP Strategies, an organization that helps with disaster recovery.

While Miyamoto was walking through the homes, he was not only looking for cracks, but also searching for their cause, and whether they indicated structural damage.

The Pacheco's pink home was riddled with cracks throughout the interior. Miyamoto explained that in most cases those aren’t indicative of structural damage, but he was concerned about the Pacheco's concrete front wall.

"That wall you just saw could be dangerous because it could come down (and hit) people. It’s what we call a falling hazard," Miyamoto explained. The wall he was referring to could fall into the living room of the house and cause tremendous damage and harm someone if they were inside.

In addition to the cracks in the walls, there was a large crack going length-wise across the floor through the middle of the house.

"A crack needs to be 1/8 to 1/4 inch in order to be considered dangerous," Miyamoto explained.

The crack in the middle of the house fit the bill. It was dangerous. Everything from that crack toward the back of the house had tilted slightly backward. After that discovery, Miyamoto shared his concern about the potential for cracks in the columns holding up the pink house.

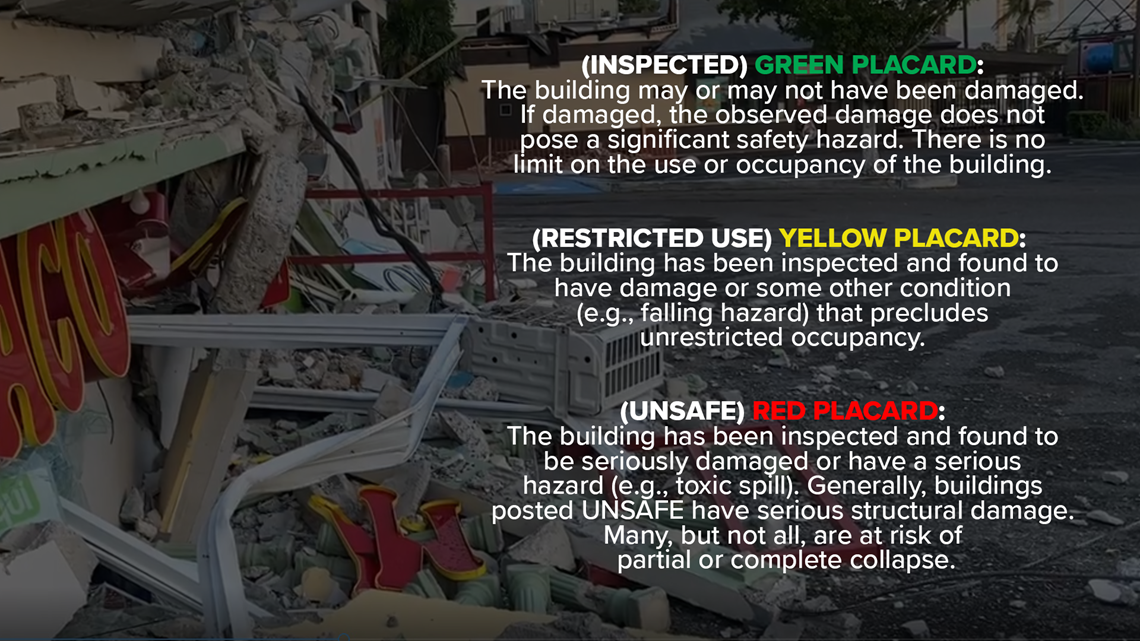

The assessment of the house that Miyamoto is working on is called ATC-20. It’s an international safety evaluation of earthquake-damaged buildings. After a house is inspected it is given one of three designations: green, yellow, or red tag.

For the most part, houses in Puerto Rico are built to withstand hurricanes, not earthquakes. That’s why, Miyamoto explained, concrete construction is what you’ll see in most homes on the island, but concrete homes not built to code become incredibly unstable after an earthquake. Wood-constructed homes, on the other hand, fair better in earthquakes.

The Pacheco’s house was made of both concrete and wood. Sounds likes the perfect combo, right? Not quite.

"It’s my understanding that about 60% of all housing construction doesn’t have a permit (in Puerto Rico)," Miyamoto explained to me.

He had been surveying the structural damage caused by the earthquakes throughout the southwest corner of the island before I got there. From what he saw, many of the damaged houses have a similar construction: they’re built on top of columns.

"Those are the most dangerous ones," he said. "Just imagine. You have this heavy construction standing on top of toothpicks. It looks dangerous. You don’t have to be a structural engineer to say that."

Construction using columns is referred to as soft construction. By Miyamoto’s estimate, there are about 150,000 buildings like that in Puerto Rico.

But when you don’t want your house to flood in a hurricane -- which is what they’re used to -- then which construction style should you choose?

"If you design per code of concrete structures," Miyamoto explained, "They are both hurricane and earthquake resistant."

If your home is already built, he says there are cost-effective ways to retroactively make buildings much stronger. We went below the pink house so that he could explain to me what those adjustments might look like like.

Below, WUSA9 takes a tour of two earthquake-damaged houses in Puerto Rico:

After touring the foundation of the pink house, Miyamoto determined that the structural stability could get a green tag, but the interior of the home would be labeled a yellow tag.

That means that the structural stability of the foundation is the same as before the earthquake, but the concrete wall in the front of the house poses a threat of damage.

The Pachecos cannot live there until it is fixed.

"Regardless of damage or not, I don’t like this kind of build," Miyamoto explained as he walked through the bedrooms in the lower section of the pink house. “In some areas, I saw 50% of houses with this style of construction had collapsed. Fortunately, in those cases, people were sleeping upstairs, so nobody died from that… but that could be different next time.”

His colleague, Sabine Kast, a disaster recovery specialist, noticed many cracks on non-structural walls in that area.

“Those types of things collapse quite a bit,” he said. "During the next big earthquake this building may perform differently. It performed fine in this case, but that may not be true for the next."

“Ten percent of the building stock in the area has sustained damage labeled with either red tag or yellow tag. About five percent of the build stock is not repairable. They need to be taken down.”

For the Pacheco’s pink house, Kit believes the fixes needed on the upstairs could be done quickly and cost-effectively. He suggested increasing the width of at least four of the columns (to about shoulder-width) with sheer wall and rebar. Doing that, he explained, creates a bracing structure that would increase the safety factor by five.

How much would something like that cost?

Kit couldn’t give me a figure for the repairs, but for any new construction on the island that plans to use the column structure, he says the added cost to build to code would be less than 1% of the total cost to build.

"Somos una familia pobre… humilde (We are a poor family... humble)," Mike Pacheco told me as he described his family’s limited financial resources.

It costs $15 a day to run the generators that he’s using to power the appliances in the makeshift home, and that alone is making finances tight.

Without the money from FEMA, they won’t be able to fix the pink house.

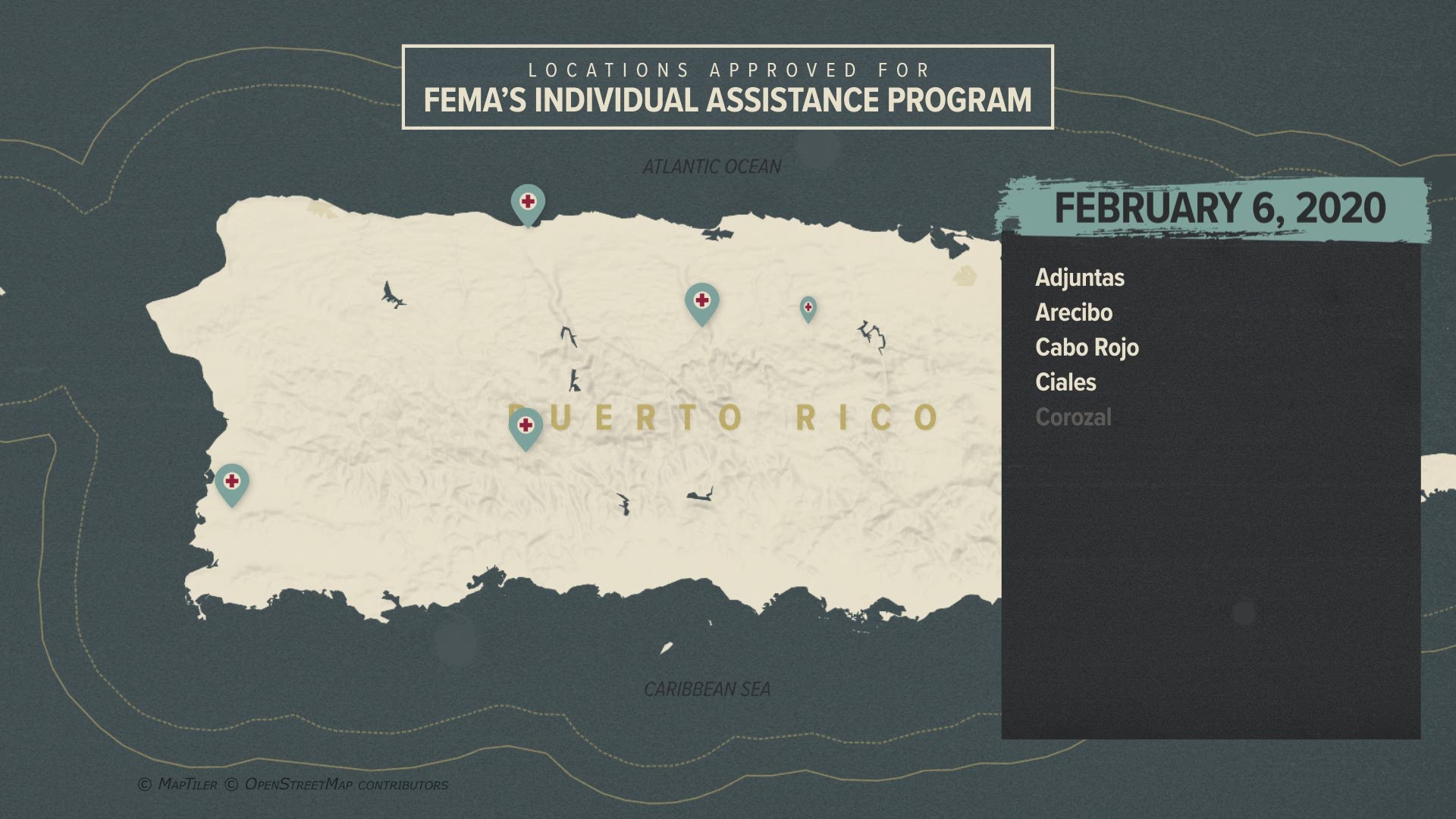

On January 16, just two days before I got to the island, President Donald Trump made a disaster declaration for the island of Puerto Rico. That declaration ensured families affected by the series of earthquakes that began on December 28 would get funding to repair or rebuild through FEMA’s Individual Assistance Program.

As of February 6, 25 municipalities have been designated as eligible for that program: Adjuntas, Arecibo, Cabo Rojo, Ciales, Corozal, Guanica, Guayanilla, Hormigueros, Jayuya, Juana Diaz, Lajas, Lares, Las Marias, Maricao, Mayaguez, Morovis, Orocovis, Penuelas, Ponce, Sabana Grande, San German, San Sebastian, Utuado, Villalba and Yauco.

To date, 5,185 Individual Assistance Applications have been be approved and more than 11 million dollars have been allocated to individuals and families.

When the topic of FEMA came up in conversation at the Pacheco house, Sabine Kast, a disaster recovery specialist, explained.

"FEMA funding doesn’t apply to people that don’t have land rights or land titles, which means that they would fall through the cracks," she said. "These are often the people that would need assistance the most."

Mariela, with DP Strategies, met with the central government of Puerto Rico just a few days before we met. In their meeting, she told us that this exact issue was addressed.

“We are asking for some specific guidelines for how it is all going to play out. If it’s going to be through FEMA or work with CBDG funds or even if the government is going to access other federal funds," Kast said.

She says that is still part of the plan that they are structuring.

Mariela didn’t know the exact percentage of families affected, but she highlighted that “this is a big reality [for Puerto Rico]. There’s a lot of people who have family owned [property]. So it’s just one person to the name and then you have a lot of buildings attached to that central home. So it definitely raises many questions that are still to be identified.”

She added that this is where non-profit funds are useful, especially because government funding, in whatever form it is delivered, is not immediate.

“When it looks like a red tag, it usually is.”

We were standing by the foundation on the pink house when Kit glanced over to the blue house and immediately assessed that it was a red tag. He was still about 5 feet away, but, he said," When it looks like a red tag, it usually is.”

The concrete columns were so damaged that you could see the metal bars helping to give the entire home support. They were thin and rusted. Kit equated the importance of the tie reinforcements to the steel straps on a wine barrel. Without those straps, the barrel would fall apart. The tie reinforcements on the Pacheco’s blue house, Kit noticed, were about five times thinner than they should be. There were also less of them than there should be to provide ample support.

“Physically speaking, this should not exist. This should have collapsed a long time ago," Miyamoto said.

But because Mike knew to put in a shoring (a metal pole that adds support to a structure) after the first earthquake, the house was still standing.

“Without it, this is really dangerous,” Kit added as he walked underneath the blue house.

In order to reestablish the structural integrity of the foundation, Kit explained to Mike that he would need to re-build some of the columns of this house with the sheer walls that he previously suggested for the pink house.

“With the public funds available [through FEMA] for this kind of damaged houses,” Kit explained, as concern built on Mike’s face, “repairing it and retrofitting it is definitely feasible.”

Mike told me that his family built these homes little by little as they had access to the funds needed. That’s the way many people build their houses on the island, he said.

"In 2010, Haiti had the same thing, but they weren’t as lucky as here,” Miyamoto said. "They lost 300,000 people."

He attributes better quality construction of the homes in Puerto Rico with the differences in fatalities between the two major earthquakes. Only one person has died as a result of the earthquakes so far in Puerto Rico.

"The construction type [in Puerto Rico] is unique," Miyamoto said, referring to the use of columns to support the structure. “I’ve never seen anything like that."

He believes that if the column structure is built properly, it can be quite safe.

"But none of the houses that I saw have good detailings," Miyamoto explained. "That makes a difference."

I asked Mike how he learned to build homes.

"By watching others," he told me.

People should build their houses with permits and to code, sure, but the reality of the situation is that people don’t always have the means to do that. In those cases, I asked Miyamoto, what can be done to make sure that people who are building their own homes know the best practices.

“In Port-au-Prince our team trained almost 7,000 masons to construct 12,000 houses out there," Miyamoto said. "Today when you go to Port-au-prince, habits have completely changed. You see actual good detailings with rebar and all of the ties that I was talking about. You can see it even in informal areas where there’s no enforcement at all because the masons understand how to do it right.”

Miyamoto was able to do that work through a program instituted by the government of Haiti in conjunction with the World Bank. I was curious if a similar program existed in Puerto Rico. The answer, Miyamoto told me, was no.

“I think that after this earthquake things will change now that they see how dangerous those houses are,” he said.

But even if engineering firms like Miyamoto’s were brought into Puerto Rico to activate a similar program, he believes that it would take years to see the culture change.

"Those masons are professionals," Miyamoto said. "They’ve been practicing the one technique for years. Changing their habit is no easy task. You can’t just give seminars; you have to work with them."

From what Kit learned from his work in Haiti, this program not only helps the masons learn how to implement the changes but understand why those changes are necessary.

The only other place that Kit could recall with a house structure similar to the houses on columns in Puerto Rico are the ones in Hawaii. But in Hawaii, he says, there is less seismic activity, and 100% of their houses are permitted.

I spent my last full day in Guanica, ground zero for the earthquake's damage. It was overcast, which seemed fitting given the level of destruction that we saw. Entire buildings were reduced to rubble. Caution tape lined the streets, red and yellow tags were hung or spray-painted onto buildings so damaged that building might not be the best word to describe them anymore. I had never seen anything like it before.

And the smell. We walked down the main street of Guanica, the smell of rotting food was strong. It had been two weeks since the magnitude 6.4 quake that caused power outages across the island.

I spotted a group of people gathered outside of a dentist’s office. That’s where I met Ruth. She’s from Guaypao, but was in Guanica for the day.

She told me about two buildings on that main street that have become iconic images of the earthquake’s damage. The first was a lavender, two-story column house with beautiful tile work and a prime location on the main street of Guanica.

Ruth told me that her friend from high school used to live in that house. Her name is Blanca Rosa Castilliano.

"Blanca’s house was built years ago,” she said. “It was precious and elegant. I always loved that house.”

Castilliano’s house is now completely uninhabitable.

The other building that Ruth told us about was at the very top of the main street. The building was two stories with apartments on the top floor and a Taco Maker restaurant and pharmacy on the bottom floor.

“That building is owned by my brother in Christ. We are from the same church, La Iglesia de Dios Pentacostal de Guanica," Ruth said. “They’re a bit older now.”

This building was this their business. They lived in one of the apartments, rented out the others and leased the space below to the restaurant and pharmacy.

“It makes me sad to think about how much they have lost..."

Guanica seemed desolate. Other than the 10 people I saw on the main street, it seemed like the town was deserted. Deserted by everything except dogs. The sound of dogs barking drowned out any possibility I had of hearing the ocean. We were about 10 blocks from the beach, but you never would have known it.

I hopped in the car and navigated around the streets blocked with caution tape and cones in the street. Whole blocks were off-limits.

The single-story houses seemed to fair well for the most part, but almost every two-story column home I saw had damage. On a street with three damaged two-story homes, I spotted a man sitting on the porch of a bright green house with salmon colored trim.

I parked the car, walked over to him and asked if it was just me or if the town really was desolate. He told me that about 80% of his neighborhood left for the States to stay with family. The green house with salmon trim is his parents’ house. The earthquakes toppled things over in their house, but structurally, the house was safe.

That didn’t matter though. He and his parents had been sleeping at a camp with more than 100 people near Lajas.

"The camp is far from trees, houses and power cables because the people are scared something could happen if another big quake hits," he said. "We’re staying in our cars and in tents."

They picked Lajas because, he said, they don’t feel the tremors as much.

We were about 10 minutes into the conversation before we stopped to find out each other’s names. His is Juan Galarza.

I asked him when he thinks his family might return home for good.

"When the tremors calm down," he said. "Last night wasn’t too bad, but two nights ago it was very active. We’ll come back when the tremors have slowed down for multiple days."

"At night when you’re in bed you look at the ceiling and you’re scared. Scared the everything will start shaking and fall on top of you… It’s an unimaginable fear.”

He was at his parent’s house for the 6.0 and the 6.4 earthquakes that hit on January 6 and 7, respectively.

“It felt like we were in a toy house, swaying back and forth like we were in a hammock,” Galarza said.

I asked him why he stayed in the house after the first earthquake.

“We didn’t think there would be another big one," he said. "We were wrong.”

Since January 7, his family has been sleeping at the shelter, but they come back during the day.

His dad takes care of the neighbors’ dogs.

And boy, were there a lot of dogs. I’m not joking. This one street had nearly a dozen dogs roaming around and barking. A really cute and friendly white dog was glued to my side. I think he wanted to be my best friend. He might have just been hungry. I like the first assumption better.

The white modern two-story house that he built for his ex-wife and their kids was labeled with a red tag. It looked as if it had been snapped off the columns. It leaned to the side, resting on the house to the right.

“The house is uninhabitable. They have to demolish it now,” he said with a look of disbelief.

He is waiting to see if FEMA will pay not only to rebuild the house but to demolish it first.

“That is the uncertainty that we all live with," Galarza said. "We don’t know what’s going to happen next.”

Juan introduced me to a woman down the street. She was cleaning out her father’s house. The smell from the main street was strong in this house as well. Flies were swarming around the refrigerator as she pulled out leftover food that perished in the absence of electricity.

After the big earthquake, her dad asked to stay with their family in Ohio.

“He couldn’t handle being here," she said. "He felt like he was going to die.”

“He just wanted to have his house back to normal," she said. "He wanted to live like he did before, with his chickens and enjoying his patio. But he’s not going to be able to do that anymore."

"Now that he left for the States, I don’t think he’s going to come back. I think he’ll end up dying there,” she told me with tears in her eyes.

Where do we go from here?

Later that night I went back to my hotel. Normally, I’d go out to a local restaurant for dinner, but I was emotionally and physically spent. I decided to eat in the hotel.

They had my favorite Puerto Rican dish: pionono! It’s plantains, stuffed with ground beef and olives, onions and tomatoes (or in this case filet mignon) and topped with cheese. Drool-worthy.

I’m a journalist and Puerto Rican, so I love to talk to people. That’s why nine times out of 10 you’ll find me eating at the bar in a restaurant chatting with basically anyone. That night, I was talking to the bartender. His name was Alexis.

"In the States that names is for girls, right?" he asked me, already knowing the answer.

"I actually have a cousin named Alexis," I told him.

He proceeded to tell me about his two daughters, his girlfriend, their recent trip to Disney. Just normal chit-chat. Then I asked him how they all fared in the earthquakes.

"Not so good," he told me. "We’ve been staying at a shelter because our house isn’t safe."

I had been pretty good about keeping my composure while hearing the stories about how much people lost throughout the trip. I’d get sad, but I wouldn’t cry in front of them. I don’t know if it was how tired I was or that I’d just heard so many stories, but my body couldn’t take it anymore. I couldn’t hold back the tears any longer.

I realized at that moment that I was going home in the morning. I was going home to electricity, my own bed and the security of knowing that my roof would not come crashing down and kill me in my sleep.

Alexis didn’t have that security.

He was going to leave his job at 1 a.m., drive to the shelter, hug his girls and try to sleep. The next day, he’d have to do that again. And again.

For him, there isn’t an end in sight. He doesn’t know exactly when the FEMA money will come through nor how much money he might get. How long will it take to fix the damage in his home? How much longer will he sleep in a place that is not his home?

He doesn’t have that answer, and neither do I.

This week, there aren’t any earthquakes of a 6.0 magnitude or greater forecast for the island. But just this morning, the southwest corner of the island felt a 3.09 and a 3.25 magnitude quake. And, as Juan said, every shake brings with it a level of fear that is unimaginable.