CRISFIELD, Md. — Public housing is supposed to be a solution to homelessness, not a cause of it.

But in Crisfield, a city of 2,600 on the Chesapeake Bay, the housing authority is one of the leading eviction filers. It files cases against tenants so often that officials hired a contractor to automate the process.

The agency owns just 330 units yet filed 718 times in 2019, all over late rent. In nearly 30% of those cases, records show, tenants owed less than $100.

What's happening here isn't an anomaly.

The work of the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism is supported by grants from the Scripps Howard Foundation and the Park Foundation. The center, located in the Philip Merrill College of Journalism at the University of Maryland, honors the legacy of journalism pioneer Roy W. Howard.

The Howard Center for Investigative Journalism analyzed four years of eviction data for Crisfield and four other public housing authorities with aggressive filing records — in Minneapolis; Oklahoma City; Charleston, South Carolina; and Richmond, Virginia — to find out why these important anti-poverty agencies are taking so many of their clients to court.

Late rent payments were by far the leading reason they sought to evict tenants. In some cases, the debts were so small that it cost the agency more to file the case than was owed.

Diane Yentel, the president and CEO of the National Low Income Housing Coalition, said public housing is "meant to accommodate people who are having difficulty paying their rent, because they have very limited incomes to begin with.''

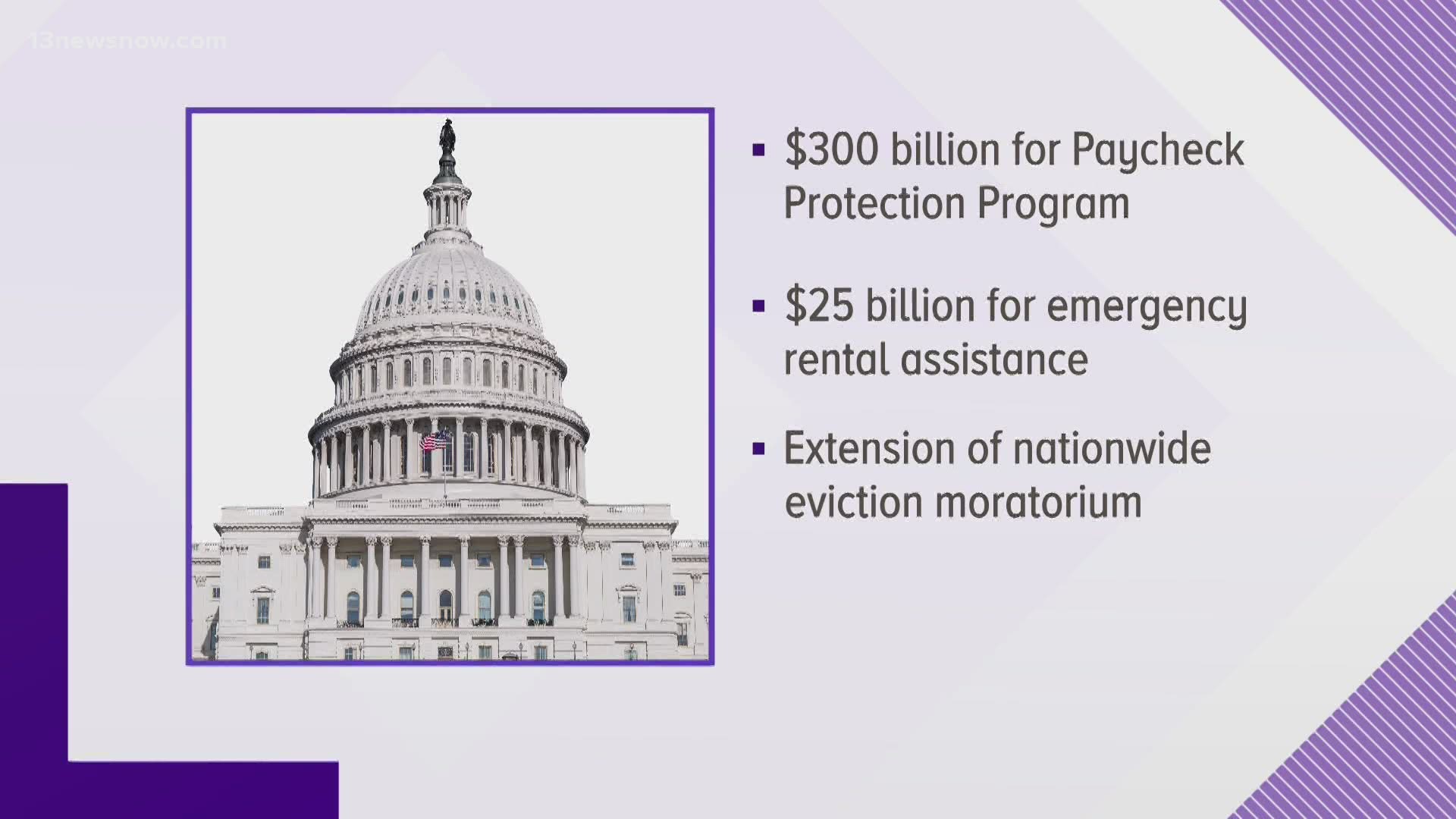

But the program has been underfunded by Congress for decades, leading some housing authorities to adopt unyielding approaches to rent collection so they can sustain their operations.

"If you owe a dollar, you owe a dollar," said Don Bibb, executive director of Crisfield's housing authority.

Yet for the tenants, many of them single parents with young children, it's not that simple.

In Crisfield, Tawna Thomas, 26, said she cobbled together the cash to stave off court proceedings for her first eviction filing in 2018 — not long after losing a pregnancy and a job. But that didn't solve the bigger problem.

Each month brought fresh worries about how to pay her $138 rent, she said. Thomas, the mother of a 5-year-old, received five eviction filings in an 18-month period, according to court records. Although she hasn't been served an eviction notice in 2020, she said she worries that day is coming. Especially when the sheriff's vehicle rolls up.

"My heart starts fluttering every time," Thomas said. "What if he has a paper for me? How am I gonna pay this?"

Federal and state restrictions during the pandemic have temporarily slowed but not halted the pace of rent-related eviction filings, records show. They place the onus on tenants, who typically lack legal representation, to prove they can't pay due to COVID-19.

Some housing authorities use the courts like collection agencies, putting pressure on clients to pay up. The Howard Center data analysis found many tenants with multiple eviction filings in the same year.

This practice piles court costs, late fees and interest onto what families already owe in rent.

Maryland Attorney General Brian Frosh assailed such use of eviction court. In a Dec. 11 op-ed in The Baltimore Sun, he said he would ask the state legislature to increase the filing fee from $15 — one of the lowest in the country — to at least $120, the national average.

Martin Wegbreit, the director of litigation at the Central Virginia Legal Aid Society, said the use of eviction filings "as a collections tool … against financially struggling tenants simply is indefensible."