NORFOLK, Va. — On a warm Friday afternoon, Rocky Mount, Virginia cosmetologist Bridgette Craighead scurries around making last-minute arrangements for a march to the Franklin County courthouse and the demonstration to follow.

A crowd is expected to travel about one mile from the Farmer's Market to the courthouse and gather in front of the Confederate monument that protesters have been fighting to have removed.

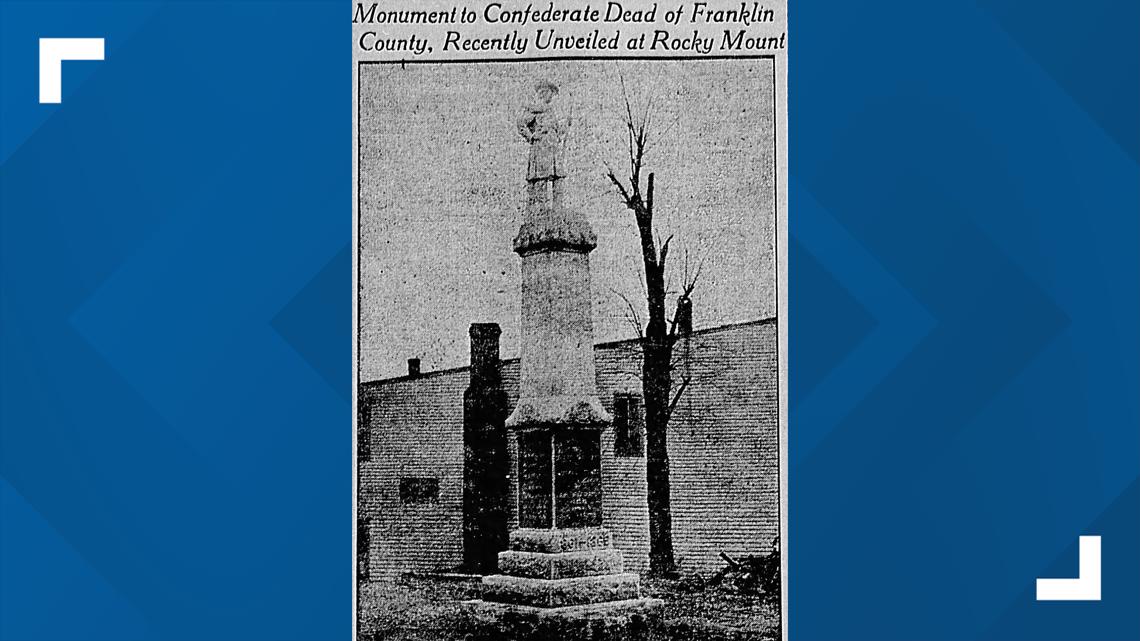

The statue was erected in 2010 after the original structure, which was built in 1910, was destroyed in a truck accident. Its removal failed in a Nov. 3 referendum to voters.

Craighead was not surprised.

"The Black people might feel they need to leave here if Black voices are not being honored or represented by the county, then why should we stay in a place that doesn't care about our voice?"

Rocky Mount is a scenic, charming small town about 24 miles southwest of Roanoke, nestled along the Blue Ridge Mountains. About 75% of its 5,000 residents are White, while 22% are African American. Its claim to fame is being the moonshine capital of the world.

The Jubal Early Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy spearheaded the erection of the monument that is inscribed with the Confederate General's name. The chapter still exists today.

As with most Confederate monument unveilings in the late 1800s and early-to-mid 1900s, large crowds gathered to celebrate their Confederate dead, including prominent Democratic politicians.

Congressman, E. W. Saunders spoke at the Rocky Mount unveiling. When he was chairman of the Virginia State Democratic party, he once declared that Democrats have always been in favor of White supremacy. To those who want the monument removed, his words, along with the words of the Confederate General Jubal Early, are proof that the monuments were intended to represent more than just war-time bravery and valor.

In his book, A Memoir of the Last Year of the War for Independence of the Confederate States of America, Early, a strong defender of the Lost Cause, described slaves as "degraded Africans."

He wrote, "The Almighty Creator of the Universe had stamped them, indelibly, with a different colour and an inferior physical and mental organization."

"These people actually think that they did Africans a favor by bringing them to America," said Franklin County School Board member and author of A Time to Protest, Penny Blue. "Until this country comes to grip with its true history, it will become difficult for us to heal and come together and move forward."

The morning after the march, the Farmer's Market is abuzz with mostly White vendors and customers looking to score a good deal on homemade pastries, jewelry, honey, and even quail eggs.

Attitudes are different. Angie Benge, co-owner of Dad's Hotdogs and Catering, is a Rocky Mount native and thinks talk of the monument only promotes divisiveness.

"This is God's world. He made it. He created it and -- all of this nonsense of hate? And I get it. All Black lives matter, all White lives matter, all Indian lives matter, all Chinese. We have to come together."

Both Blue and Craighead promise that the fight to remove the statue will continue, in spite of the Election Day setback. They both believe support for its removal is growing.

United Daughters of Confederacy

Since 2014, the state of Virginia has given the United Daughters of the Confederacy $665,000 in taxpayer funds to maintain Confederate cemeteries and graves, according to the Department of Historic Resources.

No organization worked harder to erect Confederate monuments and markers across the South in the late 1800s through the mid-1950s than the UDC. They’re known as the leading Lost Cause organization.

“So the Daughters of the Confederacy took up this charge with considerable energy because they were protecting what protected them and their privilege,” said Dr. Cassandra Newby-Alexander, Norfolk State University Dean and historian.

Today, according to the UDC website, the organization, based in Richmond denounces “any individual or group that promotes racial divisiveness or white supremacy.”

But that wasn’t always the case.

State and national UDC convention minutes show the group’s faithful service to the Confederate cause. Fundraisers were consistently held to generate money to erect monuments. A focus on education included recommending textbooks for schools and reference books for libraries.

In the book, A Measuring Rod to Test Textbooks in Schools, Colleges and Libraries, written by UDC historian Mildred Rutherford, UDC members are warned to reject textbooks that describe slaveholders as being cruel or unjust to their slaves. Books about the Ku Klux Klan were recommended to children as the UDC called the Klan a “wonderful organization.”

It’s what the UDC stood for that is helping to motivate anti-monument protesters today. During a protest over the summer, the Richmond headquarters was set on fire.

Virginia’s Sons of Confederate Veterans' Chief of Heritage Defense Frank Earnest says during the Civil War, his relatives fought to protect their homes, not slavery. He travels the state speaking in support of keeping the monuments up.

Earnest's wife is a current UDC member and he doesn’t buy the idea that monuments were erected, in part, as a form of intimidation and a statement of White supremacy.

“We just feel that this idea that a South that is completely devastated, that is trying to fight to come back like a war-torn Europe, can come up with the money to make these monuments -- and you see, some of them are just amazing -- just to irritate another population, African Americans. To me that's ludicrous,” Earnest said.

Historian John Quarstein believes the monuments that feature a generic Confederate soldier were erected purely for the purpose of honoring the service of Southern troops during the war. What's lacking is context and inclusion.

"What we have to do is be more inclusionary and tell more stories. I think they should stay, however, you need to build monuments right next to them, those African Americans that served from the same county, from the same city and honor them equally."

Tappahannock

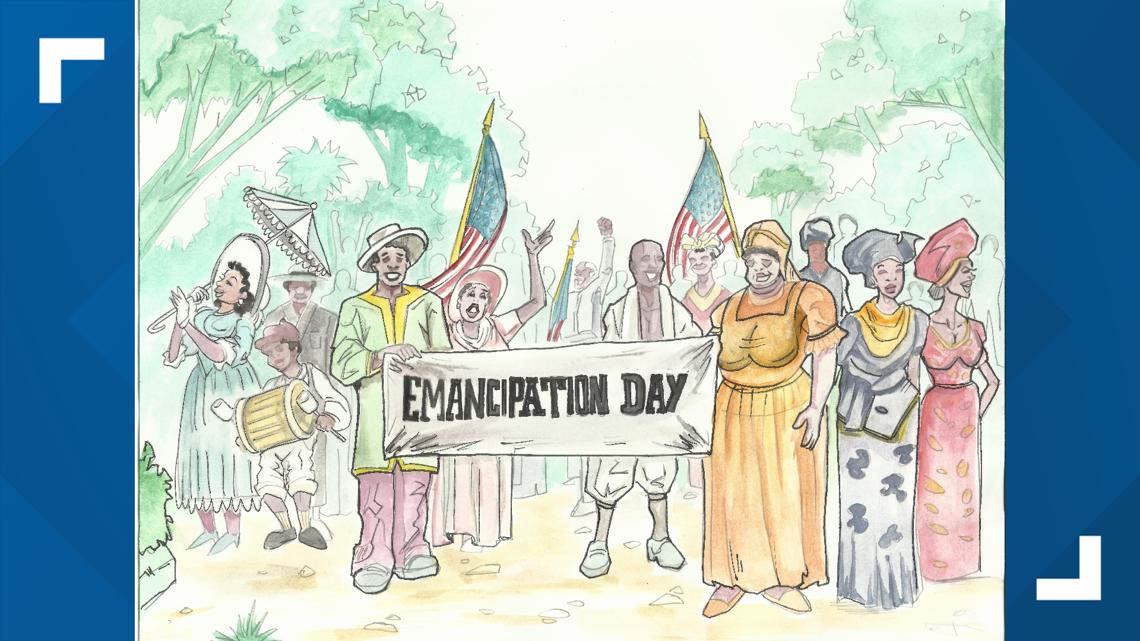

Carole Harper remembers the excitement that enveloped the town of Tappahannock every year on April 3. That was Emancipation Day.

"You saw people and you heard bands and you heard singing. It was a good day," Harper remarked.

She was a little girl when her father, who was a local NAACP president, and her mother helped organize the day’s events.

Emancipation Day marked the day in 1865 at the end of the Civil War when Union troops marched into Richmond and captured the capital of the Confederacy. African American soldiers were among the first to enter the city.

Tappahannock began celebrating that day in the 1870s until the early 1950s with a parade, speeches, singing, dancing and lots of food.

Harper read from the book, Uprooted and Transplanted: From Africa to America written by her cousin and town historian, Lillian McGuire.

"They came in early years by horse-drawn buggies, wagons or by foot. Then, as the years passed, they came by buses," the book reads.

The celebrations stood the test of time, weathering the rise of Jim Crow and the Great Depression. They were never deterred, even by the 30-foot high granite stone addition to the town square erected in 1909 that loomed over the fanfare.

"Every time we pass this, whether we know it or not, subconsciously, it's there telling us or reminding us what some people, not all, feel in the county about slavery and black people in particular," Harper said.

"I feel like the monument is a symbol of hatred and White supremacy," said Ronnie Sidney II, the organizer of the movement to have the statue removed.

When the statue was dedicated, Mississippi's governor at the time, Edmond Noel, whose father was a Virginia native, was the featured speaker. Noel's relatives' names are inscribed on the monument's base. Noel was known for authoring Mississippi's primary election law that created what was known as "white primaries," effectively excluding black citizens from political party membership and participation in primaries. Other southern states imitated the law.

Those connections to racial discrimination are what bothers Sidney as he glares at the names on the monuments and thinks about the inscription that isn't there, the name of this great-great-great-grandfather, Lewis Corbin.

"He escaped slavery. He went down to Hampton, Virginia and joined the Union Navy and came back and fought," Sidney explained.

Records show Corbin served on the Navy ship, the USS Ella, which was a patrol vessel.

"It really just energized me to remove this monument because his name is not on there. It's really just the name of people who fought for the Confederacy," Sidney said.

Sidney has organized marches, rallies and sent emails to the Essex County Board of Supervisors.

For now, the monument still stands.

As does the one in Parksley on Virginia's Eastern Shore. Opponents of the monument, featuring a Confederate soldier at parade rest, are joined by town councilman Dan Matthews.

"I'm upset that it took me 'til I was in my forties to know most of these stories. I grew up a White kid in a White school with White teachers that told the world about White people by White people," Matthews said.

Matthews feels the town is kicking the can down the road instead of confronting the unrest over the statue. Town leaders claim the owner of the land on which the statue stands is unknown, therefore they are unable to take action.

Matthews thinks the town won't pursue it because leaders are afraid to find out that the town actually owns the land, making them responsible for a decision.

John Mitchell, Jr.

At the corner of West Broad and Adams Streets in Richmond's historic Jackson Ward is a mural of former Black Planet newspaper editor, John Mitchell Jr.

The painting is one of many stops on the Walking the Ward with Gary Flowers tour.

"A black man with a newspaper in the capital of the Confederacy at the turn of the 20th century -- before Black Lives Matter had a Black fist raised as his logo for the paper -- that kind of progressivism was emblematic of John Mitchell," said Flowers.

Mitchell surfaced as an influential and powerful voice in the Black community in the late 1800s. His writings carried the weight of the dismantling of Reconstruction and the rise of Jim Crow.

Reconstruction was the period after the Civil War that gave African Americans a voice in government in which they gained Congressional seats.

"That was seen as horrible by many Whites because not only were these individuals being recognized as citizens of the country but the most important thing that a citizen can do is vote," said Newby-Alexander.

As the Jim Crow era took over, monuments began to fill the landscape across the South.

John Mitchell was watching and listening in real-time.

"The former Confederate officers are once again being reseated as Virginia state legislators having fought and killed Americans. So they had a new cause to undo, to unravel reconstruction to remind African Americans at every turn of their alleged inferiority and the statues were erected in that vain," added Flowers.

In an 1890 editorial, Mitchell criticized the erection of the statue of Confederate darling Robert E. Lee on Richmond's famed Monument Avenue, writing:

This glorification of States Rights Doctrine, the right of secession, and honoring of men who represented that cause, fosters in this Republic, the spirit of rebellion and will ultimately result in handing down to generations unborn a legacy of treason and blood.

Today, the Lee Statue still stands, months after Governor Ralph Northam ordered it to be taken down. A group of residents that lives near the structure filed a lawsuit to keep it standing but a Richmond Circuit Court Judge ruled in favor of Northam's order. The ruling is stayed, pending an appeal.

The movement to remove the monuments has merged with the battle for fair policing following the death of George Floyd at the hands of a White police officer.

As state law now affords leaders across Virginia the power to dismantle the monuments, many have chosen to do so but voters in several jurisdictions are electing to keep them standing through referendums.

According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, since the death of George Floyd, 40 memorials have been removed in Virginia.

Extra Video: 12-year-old Elijah Lee of Chesterfield, Virginia is a child activist. He tells why he feels Confederate monuments should be removed: