NORFOLK, Va. — On a breezy, sunny afternoon, Sherita Martin gazes at endless waves dancing across the ocean and thinks about that day. It was in August 2018 when she rushed down to the Virginia Beach Oceanfront with a friend looking for her adult son, Tony Martin. The day before, she reported him to Norfolk police as a missing person.

"He didn't show up for his medicine, and he never misses his medicine. So he didn't come to get it, and I'm calling him and he didn't answer," said Martin.

Something had to be wrong. After all, Tony had been diagnosed with several mental health disorders over the years, and he's autistic.

Martin spotted Tony’s car on 19th Street almost as soon as she arrived at the oceanfront. Tony was nowhere to be found. Meanwhile, her friend hit the sand to pass out photos of Tony in hopes that someone had seen him.

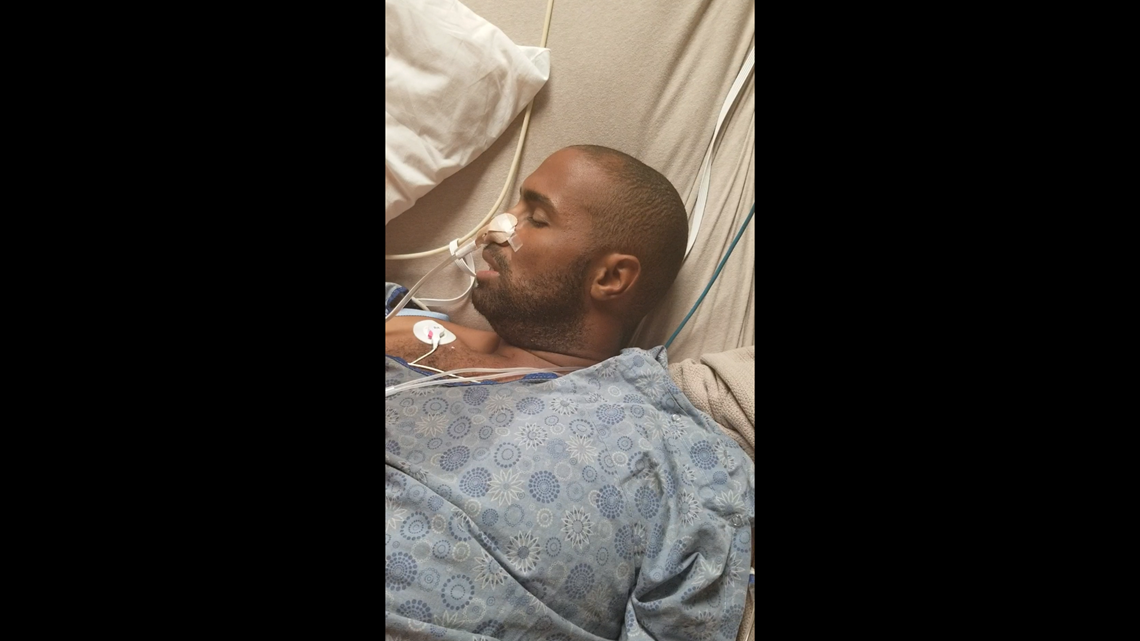

A short time later, Martin gets word that a lifeguard has pulled a man, believed to be Tony, out of the water. He was being transported to the hospital. He survived a close call, but he spent several days in intensive care.

"His hospital gown was all wet from him throwing up, and they said it was a lot of sand and seawater," Martin said.

Martin never got the full story of why Tony was at the beach, and what exactly happened to him. He told her he slept in a hotel lobby and that buildings on the oceanfront kept appearing and disappearing. She was just glad he was alive.

"That was nothing but God," Martin said about the situation.

More than a year later, Martin continues her fight to get Tony, who's 30, the remediation she says he needs to deal with his mental health problems. The near-drowning was just one of many challenges Martin has faced in a drama that has carried on for about a decade.

Martin, a divorced mother of three adult children and grandmother considers herself a fighter. Originally from Louisiana, the college graduate and retired Navy veteran and federal government civil service member, pushes through her struggles with fibromyalgia to advocate for her son.

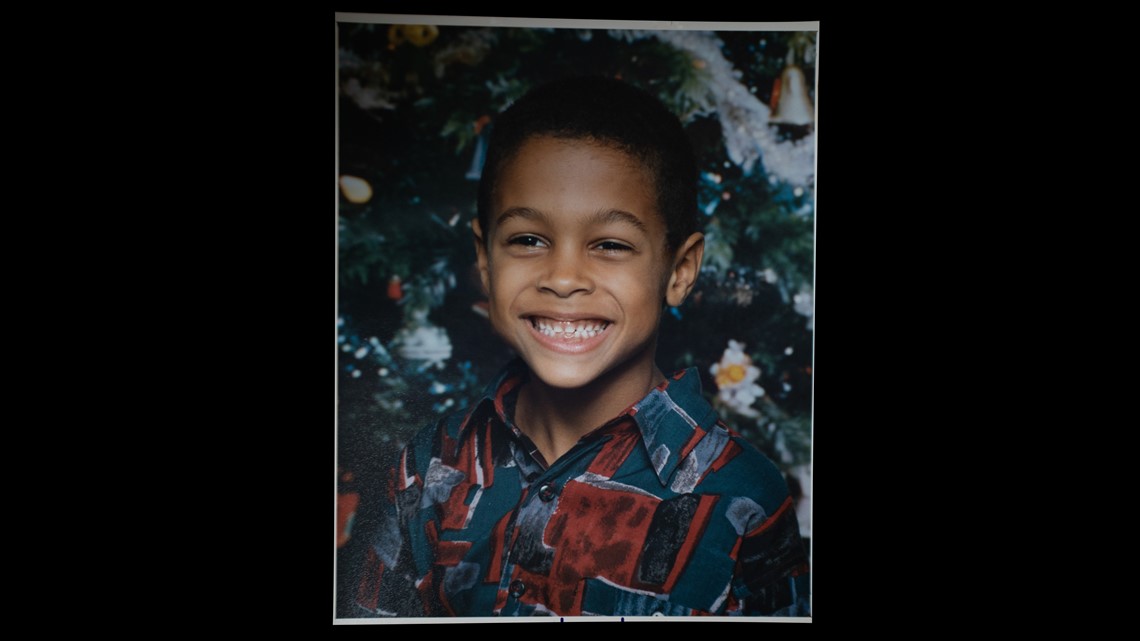

As a child, Tony was lovable and happy, according to his mother. Behavioral problems were never an issue. Around two years old, Tony temporarily lost his speech and rarely gave eye contact. Martin suspected autism. As doctors began to examine him, the prognosis was poor.

"When he as around 11, we went to a doctor that he was seeing. He was a neurologist, and he proceeded to tell me, 'don't expect Tony to do this or do that, go to college, drive or live alone or stuff like that.' I said, 'hold on doctor, my son is smart,'" Martin said.

Martin was right. For the next several years, she said Tony did well at home and in school. But in high school, he began to exhibit aggressive behaviors that Martin believes were the result of medication he was prescribed for obsessive-compulsive disorder and anxiety.

In one incident, Martin said Tony knocked her unconscious after she admonished him for not cleaning his room.

Although he eventually earned a degree in botany at Christopher Newport University in Newport News, graduation didn’t come without more unsettling behaviors.

"He struggled with anxiety. He was really anxious about graduating, what he was going to do afterward," Martin said.

Martin has watched her son’s condition decline right along with her trust in the medications he has been given. His diagnoses include schizoaffective disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety, depression, and bipolar disorder. She recalls a doctor misdiagnosing Tony with Tourette’s syndrome and prescribing more medication.

What Martin wants most is hospitalization for Tony where he can get off his medications until there's a definitive diagnosis and adequate treatment plan, particularly for a person with both autism and mental health issues. Tony recently moved into a new apartment by himself about a mile and a half from his mother's home.

Tony's therapist, Ocean Psychiatric Group psychologist, Dr. Pamela Zane has known the Martins for ten years.

"Mom feels like he's had some negative effects from the some of the medicine that he's taken and you can't rule that out. Everybody's different. People have very negative reactions to psychotropic medications. She's not coming out of left field," Dr. Pamela Zane said.

Fighting for Tony

On any given day, Martin is in her home poring over Tony’s medical records, organizing the pages of documentation she’s collected or writing emails to a politician asking for help or expressing frustration over Tony’s experiences with Norfolk’s Community Services Board (CSB).

"I feel like it's Tony and I against the world. It's hard to get help and everything I have to do. If I don't do it, it wouldn't get done," Martin said.

Tony is a CSB client. The organization works as an advocate for individuals who are receiving or require mental health or substance abuse services.

Martin said problems with CSB began when an employee threw away Tony’s medication in May 2018. Martin left the medication with CSB after a violent outburst by Tony that occurred at the Norfolk office. She said she no longer trusted Tony's actions.

"Tony got mad at me, and he punches the wall and he punches the clock and breaks the clock, and he comes by me and raises his fist at me."

Emails from Martin to CSB ask that the medication not be thrown away. CSB was found to violate human rights regulations by the Health Planning Region 5 (HPR-5) Local Human Rights Committee.

Martin said Tony began to rely heavily on Kratom, a substance found in tobacco stores that mimics opioids in high doses. That led to erratic behavior. Often he would burst into Martin's home looking for the medication she takes for fibromyalgia.

"He was coming to my house all hours of the day and night, banging on my door," Martin said.

Often afraid of her son, Martin called 911 and CSB’s emergency services more than a dozen times within a year hoping crisis intervention trained officers (CIT) would agree to refer Tony to CSB mental health clinicians for an assessment. Those clinicians are responsible for determining if an individual should be hospitalized based on criteria that specifies they either be homicidal, suicidal or unable to care for themselves.

Cellphone videos captured by Martin show contentious interactions with officers who responded to her home and refused to take Tony in for an assessment. In one video, Martin is concerned because Tony had been leaning on the hood of her car to block her from moving the vehicle.

Martin also filed a complaint when Tony was sent to Mt Regis in Salem by CSB. A Mt Regis doctor's assessment states the center was not the right fit for what Tony needed. Martin removed Tony from the center, however, CSB notes on Tony's case state Martin removed him against medical advice. Martin says CSB never responded to her inquiries about the matter.

CSB administrators would not comment on Tony’s case. 13News Now received a brief statement from a city spokesperson:

"Thank you for reaching out. We are going to decline your request in order to ensure the protection of the privacy of those involved. Here is a statement for your use.

The Norfolk Community Services Board is a Department of the City of Norfolk. It serves an average of 7,000 citizens annually. Norfolk CSB focuses services to meet gaps that exist in the system and to ensure that those most vulnerable and complex consumers are provided with quality and compassionate services. Information on the services and programs provided by the Norfolk Community Services Board is located on our website Norfolk.gov."

Martin's arrest

The troubled relationship Martin has with Norfolk CSB and Norfolk police spilled over into the parking lot of a Papa Johns restaurant on Colley Avenue in September 2018. Video captured by police body cams and Martin’s cell phone tell the story of her refusal to give Tony his prescriptions for Ambien and an ADHD medication. She explains her fear that Tony will get the medication and overdose.

"I'm not giving him that so he can kill himself. I'm sorry. I'm not doing that," Martin said.

For more than an hour, officers tried to convince Martin that she’s breaking the law.

She never wavers and at times is combative, once asking an officer if he would break the law to save his son. He answers in the affirmative. The growing impatience among the officers is captured in discussions they have amongst themselves. One white officer suggests Martin, who is African American isn’t complying because this is a “skin issue.” The same officer repeatedly tries to explain to other officers that she is trying to help.

Eventually, Martin is arrested and charged with larceny and obstruction of justice. An assault charge is added because as Martin extends her arm to close her car door and the door touches an officer.

All charges are eventually dropped and Tony was never given the prescriptions.

"In the eyes of some people, my passion is taken as a confrontational attitude, when in fact, it's the raw emotion of a mother desperately trying to save her son in an overwhelming situation," said Martin.

The incident underscores the importance of having well-trained crisis intervention officers. In Virginia Beach, every officer has at least a baseline training in crisis intervention. More than half the patrol force has advanced CIT training that is offered on a volunteer basis.

Instructor Sergeant JJ Gordon said it takes a special skill set to handle crisis calls. During training, officers learn from real-life crises that have occurred across the country.

"It can be difficult. You need somebody who has patience, who has really the skillset for that type of call for service," Gordon said.

To makes things easier, Beach CIT officers travel with a CSB mental health emergency services clinician so that assessments can be done right on the scene.

"Our emergency services clinicians are highly trained. They are certified by the Department of Mental Health and Behavioral Services. They are aware of how much patience they need to have when they are on these calls," said Angela Hick, Director of Behavioral Health for Virginia Beach CSB.

So far in 2019, Beach CIT officers have responded to more than 2,600 calls, logging more than 7200 man-hours.

When Community Services Boards' emergency services' clinicians and crisis intervention officers determine an individual needs hospitalization, they must compete with the other 39 CSB offices to find an available bed.

"We have to do a statewide bed search to all local and other psychiatric facilities throughout Virginia, and then we refer to the state hospital as the bed of last resort," said Virginia Beach Emergency Services Supervisor, Cheryl St. John.

The search proves challenging in a state with limited beds.

According to Virginia's Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Services, state psychiatric hospitals operate at 96 to 100 percent capacity. Private hospitals operate at 75 percent capacity.

Recently, the Secretary of Health and Human Resources, Daniel Carey told the General Assembly's joint subcommittee on mental health services that the state bed shortage has reached a crisis.

Gone are the days when mental health patients get long term hospitalization.

"The biggest barrier, hurdle that we have is a shortage of beds and so we still have individuals that are being held for hours, even days in emergency departments or other types of crisis stabilization," says Seaside Behavioral Health Nurse Practitioner, Jennifer Brown.

"You don't get that gift anymore," said EVMS Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Dr. David Spiegel.

Spiegel said clinicians are primarily interested in treating a patient for as long as it takes, but often they're at the mercy of what police or Community Services Boards decide.

"The clinical reason why I would put someone in the hospital is because really I want to take care of their illness. I want to take care of their bipolar, schizophrenia, their major depression, whatever it is that they're troubled with. I want to take care of that diagnosis, OK, treat them. The only thing the government, the law, cares about is are they a danger to the community or are they able to care for themselves. So it's police powers versus parent power," Spiegel said.

The Uroskie Family

There were three hospitalizations for 23-year-old Alexa Uroskie of Virginia Beach.

Her parents, Susannah and Teddy have vivid memories of the Christmas vacation when Alexa, the oldest of their four children, had her first psychotic break. She was a sophomore in college when suddenly her behavior became erratic.

"Things were just bizarre when I picked her up. I didn't understand. I didn't know what it was," said Susannah.

She was diagnosed with mania.

"I'm like, something was off. I never slowed down. I didn't even need to slow down, which was crazy. Your brain is kind of just going haywire," said Alexa.

The Uroskies said the second and third hospital stays were more traumatic. Alexa's behavior was getting more bizarre.

"We had gotten a call from police, and she had been on Virginia Beach Boulevard near a motel digging through dumpsters. God had told her to recycle," said Susannah

"I remember I thought I was a fairy," Alexa recalls. "I thought the devil was inside the house, so I opened up all the windows, and if I did this thingy, they would all go away."

Suddenly the Uroskies found themselves thrust into the confusion of having to navigate a complicated mental health system.

"Unfortunately, you don't have a number where you can pick up the phone and say there's something wrong with my child. What do I do? The resources aren't there," said Teddy Uroskie.

They found some relief through the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) Coastal Virginia.

For them, a free 12-week family to family class was eye-opening. It pairs families of an individual affected by a mental health condition with other families for mental health education.

"Not one has entered the class and left the class not thinking that it was one of the most valuable things they've ever done, not only for themselves but for their loved ones," said NAMI Executive Director, Courtney Boone.

Alexa is now passionate about mental health and helping others. She leads a peer to peer support group and is now living on her own. "I realize I've reached a point where I'm not ashamed of it and I realize that so many struggle with it," said Alexa.

Looking for Happiness

In recent weeks, Martin said Tony's behavior has improved as he's been on mood stabilizers and off medications for psychosis.

"Tony came up to me a few weeks ago and he said, 'mom, I want to feel like I did when I was a teenager' and it just broke my heart. He has struggled and suffered so much," said Martin.

Tony is settling into a new apartment. Every day, an aid worker from Quality Training and Skill Building comes to his house about 10 a.m. to take him to appointments, errands, or to places he likes to go.

On most mornings, he heads over to his mother's home for his favorite breakfast, bacon and eggs and to take his medication. He and his mom pray together.

"I just want to be there for my son and other people like him because he's not the only one," said Martin.

Although Tony is no longer driving and working, he still has a hobby: plants.

"I like nature. It makes you feel good and everything," said Tony.

On a warm fall afternoon, he and his mother head to the Peace Garden in Norfolk's Park Place. It's a community garden where citizens can grow flowers, plants, and vegetables.

"We have dinosaur kale here, we have cabbage," Tony said as he scanned the landscape to which he has contributed.

Martin doesn't spend much time worrying if her son will get better. She's confident he will and plans to keep fighting until he does. She is starting a non-profit called the You Are Not Alone Foundation and a GoFundMe page to help other families cope with mental illness. Anyone is welcome to email Sherita Martin at tonysfight007@gmail.com.

"I've gone through a lot of things. I've seen a lot of things and I just believe God has just prepared me, been preparing me for this. So I just want to be there for my son and other people like him because he's not the only one and I don't want other families to suffer like I have suffered."

How to Get Help

Virginia Beach CSB, contact numbers can be found here.

If the situation is potentially life-threatening, get immediate emergency assistance by calling 911.

If you or someone you know is suicidal or in emotional distress, contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255) or online here.