“It’s complicated.”

That contemporary, throwaway phrase actually means something when applied to this country’s thoughts on the War in Vietnam. Mention it to those who identify Vietnam as something more than a history class or a program on the History Channel, and you’ll get many reactions. Very few are complimentary.

Chapter index:

1. OVERVIEW

“Vietnam, the only war we ever lost.”

“Vietnam, the war that Cronkite and the news media lost for us.”

“Vietnam, the war in which we never welcomed our soldiers home.”

“Vietnam, the war where our soldiers were ‘baby killers.’”

“Vietnam, the war that has paralyzed American military and foreign policy for 50 years.”

“Vietnam, the war we should have won if the brass and the politicians didn’t sell us out.”

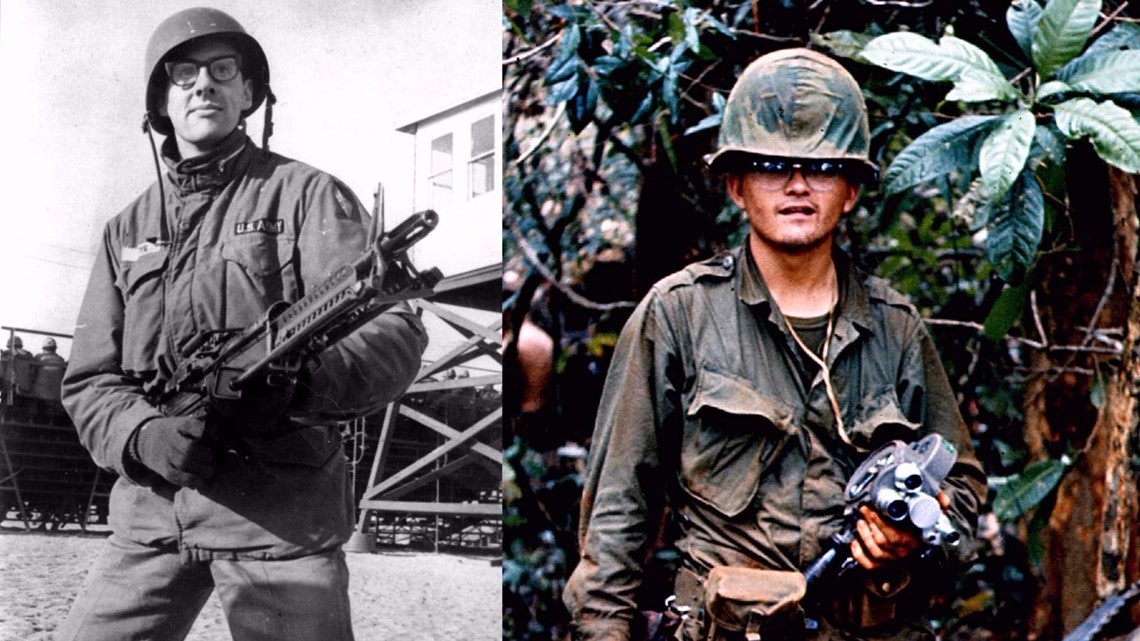

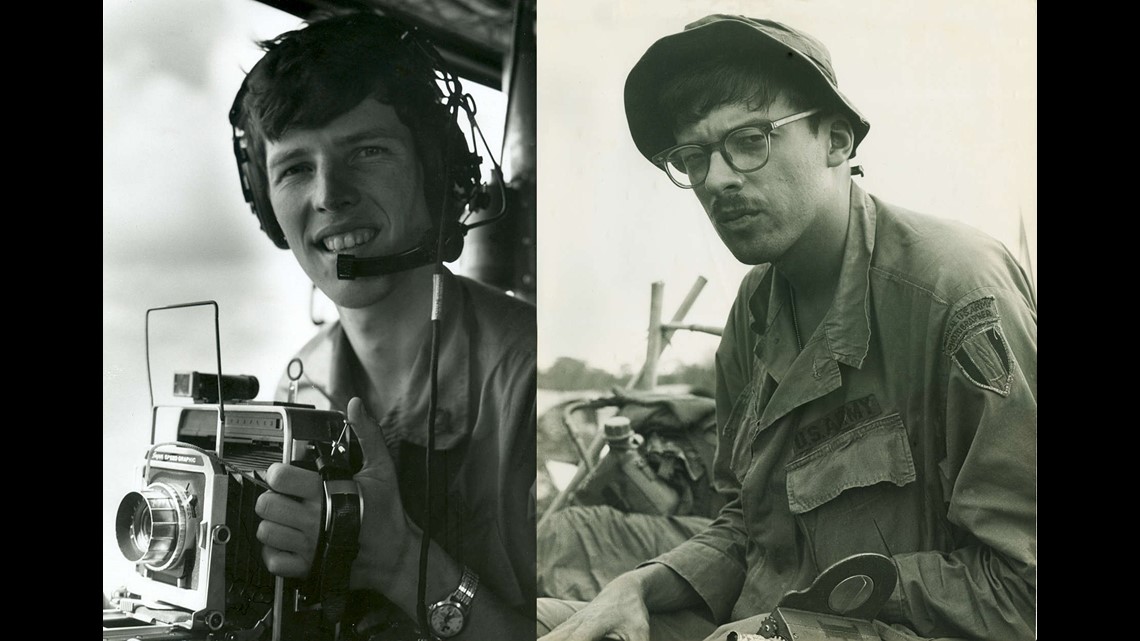

We could go on. Any conversation about that time -- a period that covered nearly 20 years from the late 1950s through the late 1970s -- brings out anger and sorrow in many. From others, you’ll hear the pride and wisdom gained from being there, including those who actually recorded the Vietnam War in video and still photos. They were in country as young men, most with no combat experience, some hadn’t picked up a camera before being trained as a photographer prior to joining their unit.

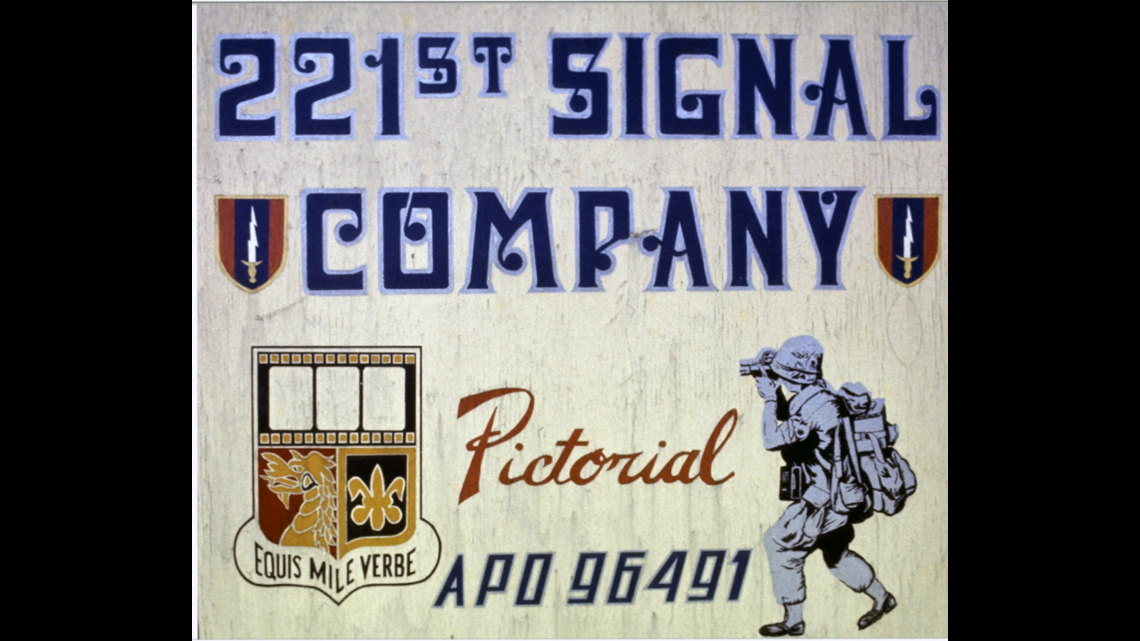

Now in their 60s and 70s, members of the U.S. Army’s 221st Signal Company (Pictorial) gathered in Phoenix for their annual reunion earlier this past spring. This group served from 1966 to 1972, building a base of operations on land that had been cleared of jungle vegetation, living and working there and all over the country while dodging Vietnam’s legendary storms and incoming rockets from an unseen enemy just beyond the barbed wire or at the tree line.

The men, and they were mostly all male, mocked up press IDs, caught chopper rides to the hot spots, and embedded with combat grunts. Literally, they saw it all, and some of what they viewed through an eyepiece while bullets flew and shells exploded around them, will be seen here. They agreed to share their work and their stories, and when pressed, their opinions about how a modern government controlling the images of war might not be such a good idea.

We are in the age of SnapChat and Instagram when everyone is carrying a smartphone with a high-quality camera, recording and posting all things great and trivial. It may feel stone aged, but during the Vietnam War, images were captured by a mechanical camera on film that had to be processed before being seen.

Further, the images were viewed in a much more concentrated form, through a single evening newscast, through a weekly magazine, or in the daily newspaper. By today’s everything-is-live-right-now standard, the exposure was extremely limited. However, the undivided attention these images received from a viewing public that didn’t have 1,000 channels of content competing for their eyeballs made their impact much more significant.

Further, when you look at this work and consider the conditions under which it was produced, you’ll feel even more awed by its impact. These photos and videos changed hearts and minds and history. And, no matter how you feel about war in general or Vietnam in particular, you will respect the soldiers who risked their lives to capture it on film.

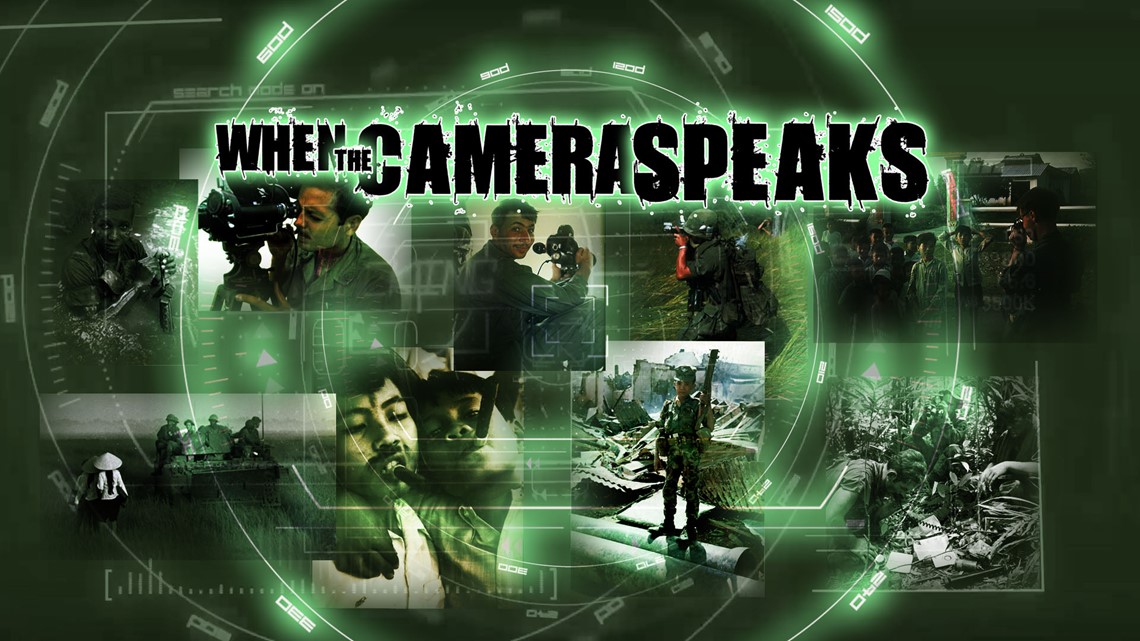

The title of this report, “When the Camera Speaks,” was chosen to let the images speak for themselves. Yes, you will get some interpretations from the men who lived the events they photographed and what they have to say is both helpful in providing context and important because of its eyewitness quality.

But, the photos speak too, and often loudly. Some will make you cringe and others will bring a smile. None, we humbly submit, will waste your time. So, read on, listen and let the cameras speak.

“…One of the things that happens is that you look through that viewfinder and you feel like you’re in a little black room all by yourself, and no one can see you.”

Roger Hawkins' phone rang. It was his daughter calling, wanting her dad to watch a TV show. “She said I know you’re very interested in Special Forces. History Channel is having a special, you know, I think you’ll want to see it.”

Chapter index:

1. OVERVIEW

He looks bemused as he explains what happened next. “So, I got my son and we sit down and we start to watch it. He said, ‘Dad you shot that, didn’t you.’ Yep. It was History Channel’s ‘Suicide Missions Behind Enemy Lines.’”

Roger speaks in a matter-of-fact manner. Listen closely and you can still hear the hint of a Western Pennsylvania accent. The calm demeanor and voice doesn’t match the Hollywood image of someone along on a suicide mission.\

Roger Hawkins is, in fact, the opposite of Hollywood. He grew up in the tiny borough of Aspinwall on the Allegheny River just north of Pittsburgh and went on to live an adventure recorded his wartime photographs. That hadn’t been the plan.

After graduating high school from Valley Forge Military Academy, Roger entered Carnegie Mellon University to study architecture. But, as he tells it. “My math skills were terrible, so I transferred into Industrial Design.”

At CMU, Roger tacked two years of ROTC onto what he’d already completed in high school and graduated as a second Lieutenant in the Signal Corps, where he was placed into his life’s work, assigned to photo Pictorial Unit Commander and Motion Picture Director’s school.

“That was the perfect place for me … the right place for me," he said.

Without a doubt. Roger’s official biography tells of impressive results of the would-be architect/engineer who ended up in the chaos of combat with a camera in his hand:

“Lt. Hawkins and his team's combat experience includes the Pleiku Mike Force (Special Forces), the 101st Airborne Division, Long Range Recon Patrol with the 173rd Airborne Brigade, A Mechanized Infantry Unit of the 1st Infantry Division, and Dust Off calls with the 82nd Medical Detachment (Helicopter Ambulance) Company. His photos and film from Vietnam have appeared in civilian media such as the Washington Post, the History Channel, Discovery Channel Wings and are currently on display at the Pritzker Military Museum in Chicago.”

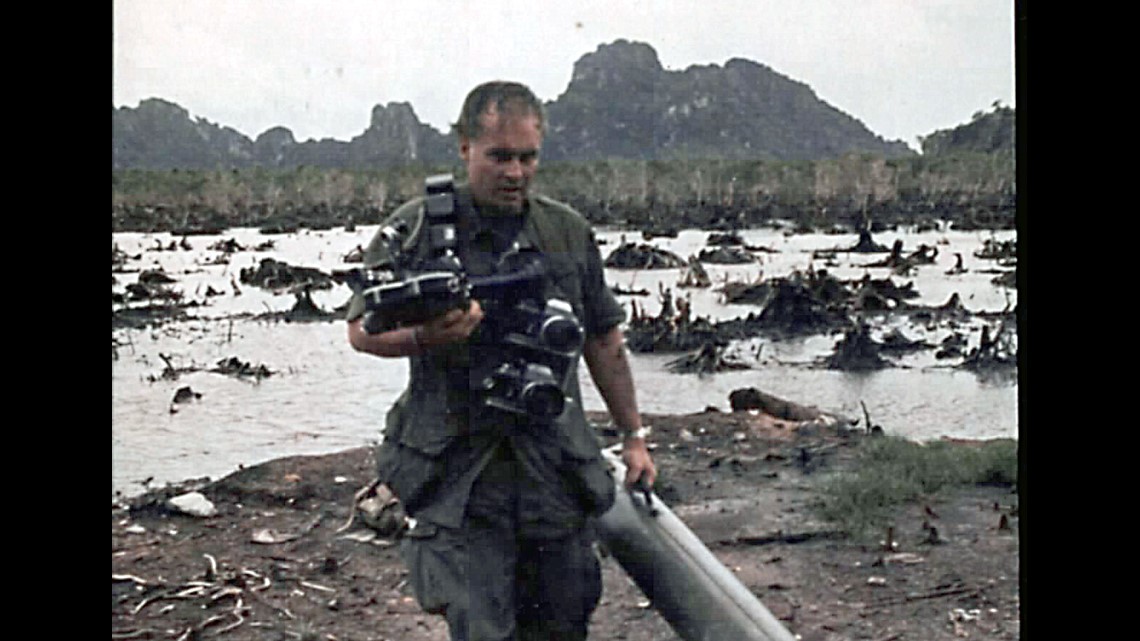

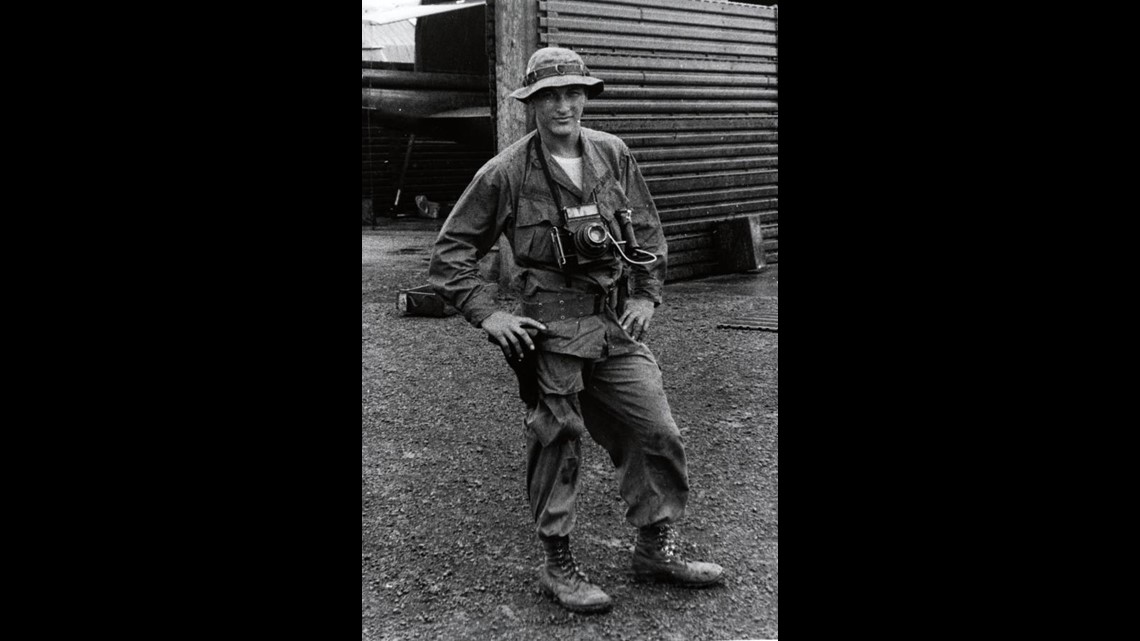

A photo of Roger from the time captures a very cool character riding in the back of a truck, camera with a long lens around his neck. It looks like he was born to do this.

“Forty-seven years ago I had a full head of hair and carried a 45 caliber pistol model 1911 in a shoulder holster given to me by a pilot. I found that running with a pistol secured to your chest works better than having one flapping against your leg. Oh yeah, it looks good too.”

Roger has clear memories and clearer opinions of what he experienced working alongside the combat teams in Vietnam. While he is deservedly proud of his service, he’s not afraid to call “BS” on those who would rush young men and women into harm’s way. Here’s a sampling of his memories spent with the 101st Airborne and embedded in Long Range Reconnaissance Patrols, also called LRRPS:

On keeping your focus in the heat of combat:

From his home in Sonoita, Arizona, Roger spends a lot of time shooting photos of birds and nature. He has the time to compose the shot, check the lighting, etc. That does happen even when you’re being shot at by seen and unseen enemies.

Roger wishes that he’d shot more images.

The heavily edited images of war that Americans see today have impacted our debate on whether to fight foreign wars.

Roger believes that if we experienced war today in the same way that people experienced watching Vietnam on the evening news in the 60’s and 70’s, we’d be more careful.

"It seemed like when I was younger you would actually see more violence on the news, and now they warn you to look away, even if there’s the smallest bit of violence," he said.

"I think it makes it too easy to go back to war. "

In the image gallery of Roger’s work above and detailed stories here, he provides crisp photographic insights and details of his exploits.

There is no bravado.

Roger is humble about his role within the fighting unit, there to record and to assist whenever necessary.

You’ll hear from him again later as we look at the 221st Signal Company (Pictorial) in combat.

“Then the sound. The loudest noise I have ever heard … I land on my back … Then the realization I’m shot … I see a blood spot on my fatigues … I tear off my pistol belt, cameras and equipment … Bright red blood is spurting up six or eight inches with each heart beat … Cyr is the one who pulled me from the line of fire…” - Ken Pollard describes being rescued by Ransom Cyr, May 28, 1968

Chapter index:

1. OVERVIEW

The assignments of the 221st were many and varied, though none are likely more memorable or important than their documentation of war. As their unofficial history proudly proclaims, “The photographers traveled the length and breadth of the country… Several photographers were on stand-by seven-days-a-week, 24-hours a day.” The chaos seen through their eyepieces resulted in what seems like an infinite amount of images of the American soldier and their allies in battle. The cost of their mission was dear. Eight died from 1968-1970 when the war was at its hottest, including five in a helicopter crash of Ghostriders 079 on May 9, 1970. The 221st has extensive information on that crash on its website, so we will not deal with it here.

One of the most dramatic photographs of the war depicts the courage of the 221st when one of its own was felled by enemy fire. Specialist 4 Ransom Cyr of Mercer Island, Washington, then just 22 and on his second combat tour, and Specialist 5 Ken Pollard of Sacramento were embedded with South Vietnamese Rangers engaging North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong in the Chinese area of Saigon. Years later, Pollard explained what happened in a letter:

“... I take a couple of pictures and ask the U.S. Marine Major what the situation is. He tells me a combined force of North Vietnamese and Viet Cong is nearby ... There is no sound around us. The place gives me the creeps. My heart is pounding. I crawl up the alley on the right side and take a picture ….I signal with my right hand to Cyr that I am going to move across the alley … Then the sound. The loudest noise I have ever heard … I land on my back … Then the realization I’m shot … I see a blood spot on my fatigues … I tear off my pistol belt, cameras and equipment … Bright red blood is spurting up six or eight inches with each heart beat … Cyr is the one who pulled me from the line of fire. He is putting a tourniquet on my body above the wound and saying over and over “God, oh God” … My vision is blurry … My arms, legs face, are numb and I seem to be fading away …I am seeing into a cloudy tunnel. The loneliest feeling in my life … “

Pollard provided the account to his friend, 2nd Lt. Paul Berkowitz, who describes what happened next:

“Cyr was awarded the Silver Star posthumously .. Cyr had dragged Pollard to safety that day – but he was not hit at that time. Pollard was taken to the 3rd Field Hospital and Cyr decided to continue his mission with some South Vietnamese Rangers. He was killed later that day in a separate action pursing his photo mission.“

Pollard recovered from his wounds and continued to shoot combat. What he witnessed haunted him after the war in the form of severe posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). There were also challenges for his wife, who died after a long illness. It was all too much for Pollard, who committed suicide in 2014.

Before that awful ending, Pollard left a message on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Virtual Wall for his friend and hero, Ransom Cyr. It simply said, “It’s been a long time. Thanks, From a buddy.”

There is also a story of the photo itself. It was not captured by an official photographer of the 221st. The man behind the eyepiece was Rick Laurel.

Paul Berkowitz has the tremendous back story:

“It’s something I wondered when I first saw it in the 221st Orderly room in Long Binh when I arrived in 1969. Who the hell got that shot? In those days, pictures did not take themselves. That’s a point we are fond of making about combat photos. It's something few people ever think about.

"The picture was officially credited to 101st Airborne IO (meaning Information Office) ... But this was Saigon, far from where the 101st Airborne operated. However, Ken Pollard confirmed to me that someone from the 101st did take the picture. Rick Laurel.

"At the time, Laurel was AWOL from the 101st. A serious thing. Pollard had befriended Laurel in Saigon and Laurel would go out on missions with Pollard and the Team. They gave him a camera and he was OJT. On the Job training. So it was Laurel who snapped the picture – then it was Rick Laurel that pulled out a 45 and commandeered a South Vietnamese ambulance which drove the wounded Pollard to 3rd Field Hospital. When they arrived at the gate of the hospital, the guard refused entry to the South Vietnamese ambulance. Laurel points the 45 at the guard and says ‘Open that gate or I’ll blow your f#*&ing head off.’ The guard opened the gates ... All this Pollard confirmed to me about five years ago.

"Laurel, AWOL from the 101st Airborne, saved Pollard’s life as much as Cyr. Meanwhile, Cyr had continued the mission with the South Vietnamese rangers and was killed a few hours later. In fact, it was Laurel who later helped recover Cyr’s body. As far as we know, Laurel returned to the 101st without court-martial – but he never did get personal credit for the photo --- until now – 48 years later. "

In all, eight of the 221st didn’t make it home. From the unofficial 221st history, an accounting and brief explanation of the deceased:

“As a consequence of their very close participation, eight 221st photographers have died as the result of enemy fire. They are:

- SP/5 Timothy Duncan, killed in Action March 1968

- SP/4 David Russel, killed in Action March 1968

- SP/4 Ranson Cyr, killed in Action May 1970

Five photographers died on the 9th of May 1970, when their helicopter crashed as a result of enemy fire while returning from a combat photo mission in Cambodia.

- SP/5 Douglas J. Itri

- SP/5 Christopher J. Childs

- SP/4 Larry C. Young

- SP/4 Ronald S. Lowe

- PFC Raymond L. Paradis”

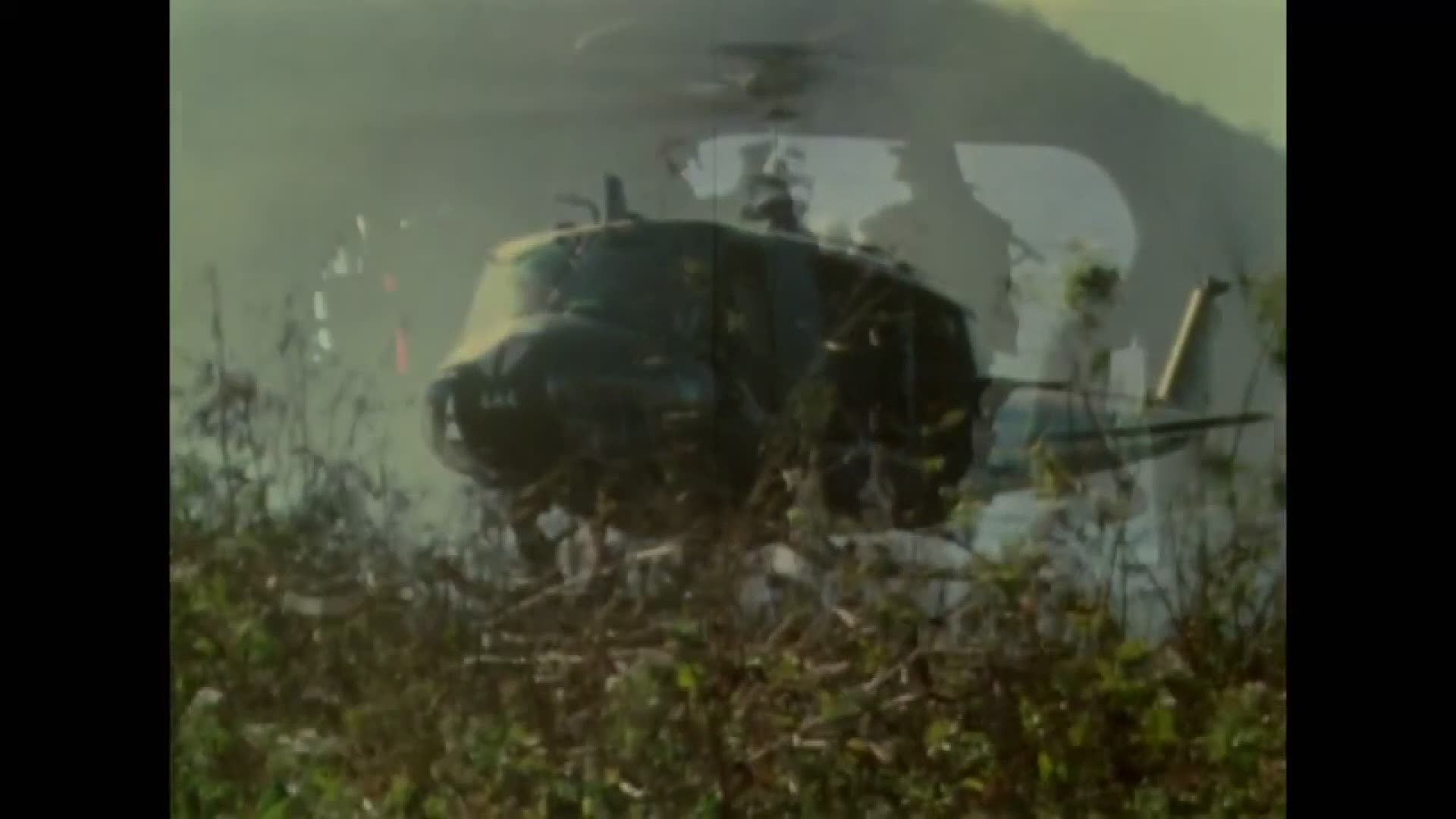

Huey’s, Medivacs, LRRPS and Firefights

“Airmobility, dig it, you weren’t going anywhere. It made you feel safe, it made you feel Omni, but it was only a stunt, technology. Mobility was just mobility, it saved lives or took them all the time…” From Dispatches by Michael Herr

The Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Association estimates that there were 12,000 helicopters in the Vietnam War and over half, 7,000 were the UH-1 or “Huey.” Over 3,000 of the ships were lost, taking with them just over 2,000 pilots and crew members KIA. It was the air taxi of the war -- a quite dangerous air taxi -- but extremely effective in ferrying troops, supplies, wounded, and dead all over the country while engaging in firefights with a hidden enemy. The Huey has become a signature of America in Vietnam – the star of movies like" Apocalypse Now," "Platoon," and "We Were Soldiers."

The war correspondent, author and film consultant, Michael Herr penned a poetic ode to them:

“In the months after I got back the hundreds of helicopters I’d flown in began to draw together until they'd formed a collective meta-chopper, and in my mind it was the sexiest thing going; saver-destroyer, provider-waster, right hand-left hand, nimble, fluent, canny and human; hot steel, grease, jungle-saturated canvas webbing, sweat cooling and warming up again, cassette rock and roll in one ear and door-gunfire in the other, fuel, heat, vitality and death, death itself, hardly an intruder. Men on the crews would say that once you'd carried a dead person he would always be there, riding with you… Helicopters and people jumping out of helicopters, people so in love they'd run to get on even when there wasn't any pressure. Choppers rising straight out of small cleared jungle spaces, wobbling down onto city rooftops, cartons of rations and ammunition thrown off, dead and wounded loaded on. Sometimes they were so plentiful and loose that you could touch down at, five or six places in a day, look around, hear the talk, catch the next one out.”

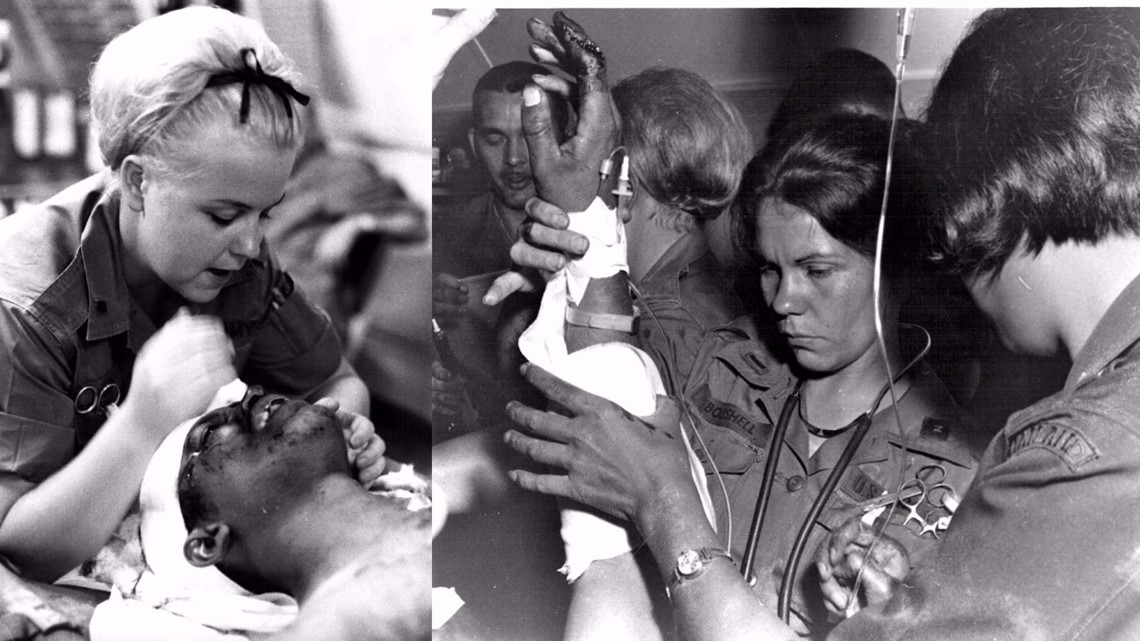

1st Lt. Peter Berlin was a Photo Team Leader with the 221st from 1969-70 and he often rode Huey’s outfitted for medical evacuations (medivac). They were called “Dust Off” operations.

“The Air Ambulances of Vietnam were Huey Helicopters sporting a big red cross. The dust offs were a great source of quick transportation to the ‘hot areas’ as they were always out picking up casualties and we could hitch a ride (the combat photo team) with them to get to the action," he said.

Not only did Berlin hitch a dust off ride to the firefights, he took an assignment on the other end, when the wounded arrived at hospitals. He captured the focus and intensity of nurses at the 36th Evacuation Hospital in Vung Tau Vietnam in early 1970.

The evacuation hospitals were not where the combat photographers wanted to spend a lot of time. While they waited for the ride out, they saw the effects of combat close-up. Roger Hawkins watched the dust offs come in and off-load precious cargo.

“As a combat photographer the last thing you want to do is hang around a field hospital as wounded are being choppered in," he said. "It is hard enough to push yourself and your photographers out onto the battlefield without being treated to the end state of humans like yourself who have just exited the meat grinder. If there is a purpose to any of it there might just be a slight chance your images will reach politicians and generals with the power and vision to find a better way to end the madness.”

Hawkins was also in some firefights where he shot one of his favorite photos called “Over Hill” then found himself in a very tough spot.

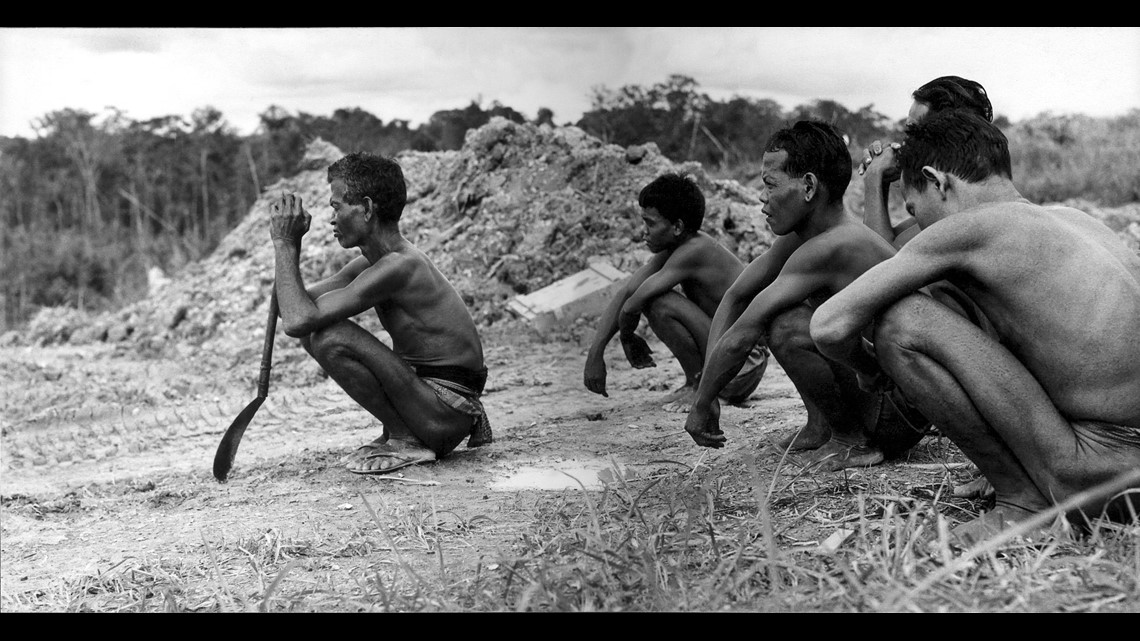

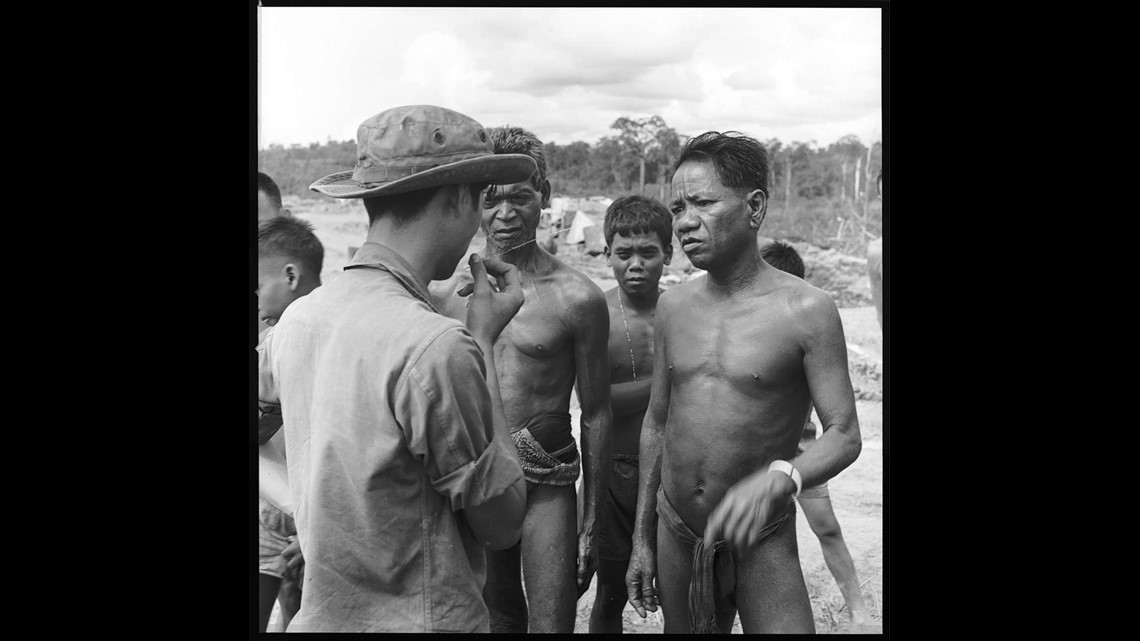

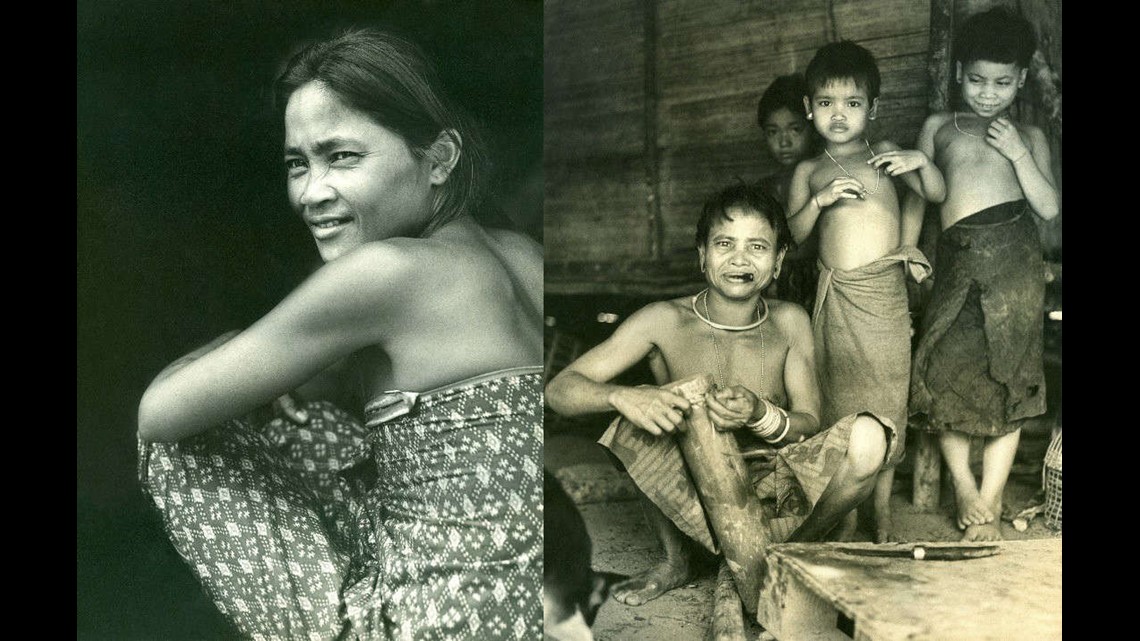

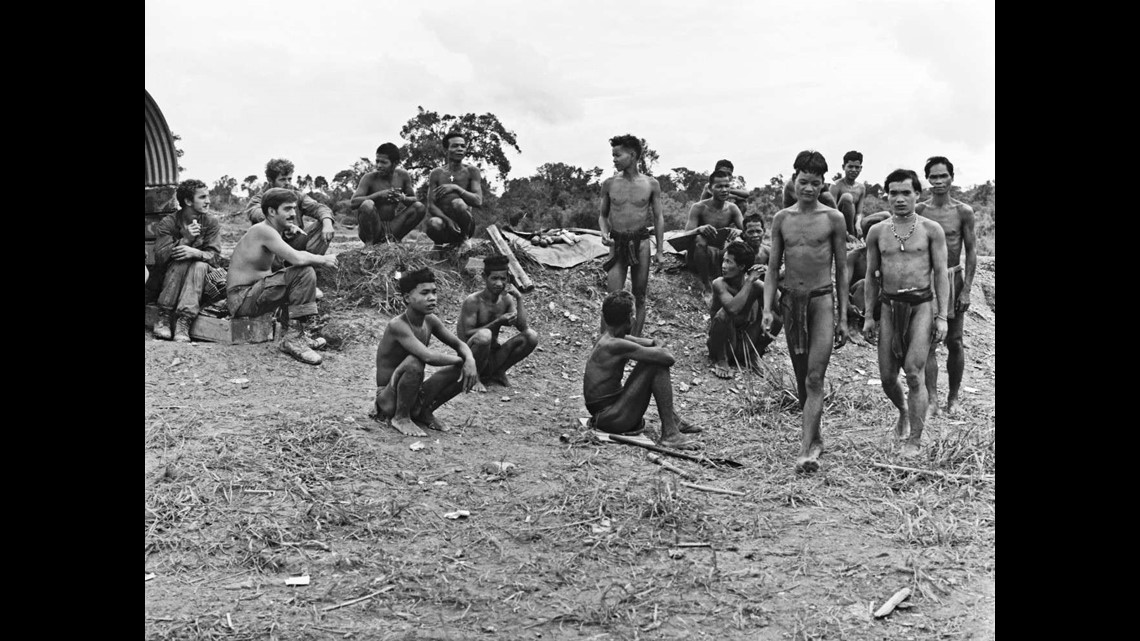

With the Montagnards in Cambodia

In 1970, the U.S. and the South Vietnamese invaded neighboring Cambodia with the objective of eliminating cells of North Vietnamese and Viet Cong who were attacking cross-border. The invasion lasted the entire month of May and sparked massive anti-war protests in the United States, including the tragedy at Kent State University in Ohio. There, national guardsmen opened fire on protestors killing four. The event shocked the nation and became known as the “Kent State Massacre.”

In Vietnam’s Central Highlands and in Cambodia, another massacre was building. The genocide of the Montagnards, French for “mountain people” would take place as the U.S. and South Vietnamese continued to lose ground to the North.

Much has been written about the Montagnards, a tribal people disliked by the central government of South Vietnam, who joined in with American special forces in a strategic move designed to gain favor for what they hoped would be independence at the end of the conflict. In fact, the opposite occurred. When Hanoi won the war, the Montagnards were hunted down and slaughtered. Many escaped into Cambodia where they live today in a no-man’s-land as refugees, still trying to stake their claim to equal treatment in their homeland. The only depiction many Americans may have of the Montagnard comes from the 1979 movie “Apocalypse Now.” It is not favorable.

Evan Mower lives in Hawaii now, where he makes his living doing still photography and shooting commercial video. In May of 1970, he was a VIP Photographer with the 221st. A lot of his service there was spent with Generals and Colonels recording their activities, but he travelled throughout Vietnam with a variety of assignments.

“I was all over Thailand and all over I Corps and III Corps documenting their units,” he remembers. “In 1970 I shot the Bob Hope Show.”

No one is shooting at you at the USO show, and that was fine with Mower. “I’m 6’5’’ and a 7 3/4 size head. Not good for combat photography.”

Then, a surprise. A new Commanding General, Major General Hugh Foster, had taken control of the 1st Signal Brigade and he wanted to see what was happening in Cambodia. Mower and his Commanding Officer, LTC Warren Colville accompanied the general on his visit to Fires Support Base (FSB) Myron in Cambodia. Colonel Colville was, as Evan puts it, “kind of freaked out by the trip,” and on his way back to Vietnam told Evan. “’We’re sending everybody up to Cambodia tomorrow.’” The news was shocking.

“’Everybody? ‘Everybody. You too.’ A group of us traveled by truck to Phuc Vinh where we all hitched rides (on helicopters) into Cambodia. I had known from my visit with the general that Fire Support Base Myron had never been hit. So, my partner Joe Wollak and I chose to go there.”

Fire Support Base Myron provided artillery cover for the 199th Light Infantry Brigade known as the “Redcatchers.” Winding down as the American incursion was ending, FSB Myron was actively decommissioning; troops and materiel moving out on big Chinook helicopters and everything else burned to keep it away from the VC.

Mower and his partner Joe Wollak were nervous. The 221st had just lost five in the crash of a Huey chopper for the 189th Assault Helicopter Company “Ghostriders079.” While covering activity at the base, Mower was talking to a couple of Kit Carson Scouts, who offered to take him to a nearby village that he was interested in, having seen and photographed it from the air. “Kit Carson Scouts” were former Viet Cong who had defected. Wollak didn’t want to go, so Mower went with the scouts and another American soldier.

“Though quite nervous, I went to the village, perhaps a quarter-mile from the base. We walked to the village, and it was like stepping back into the Bronze Age.” Mower’s recollection clearly touches him emotionally. “Amazing, beautiful people.”

He started shooting and the results are stunning, capturing the Montagnard in their daily lives as the war machine swirled around them.

Evan moved quickly - shooting many black and white negatives. While the Montagnard subjects look very relaxed, their photographer was not.

“We spent about 20 minutes wandering around. The adrenaline was rushing. I didn’t’t know if these guys were going to meet the Viet Cong to plan the final attack on the base. I just kind of dropped in and we left. “

Nearly 50 years later, Evan wants to return. He would like to get National Geographic interested in the village, which he believes is still there.

“I have the military coordinates on how to find it. I would love to go back. Every time I look at the photo of the woman at the doorway, I wonder what happened to them. They were so beautiful.”

PHOTOS: With the Montagnards in Cambodia

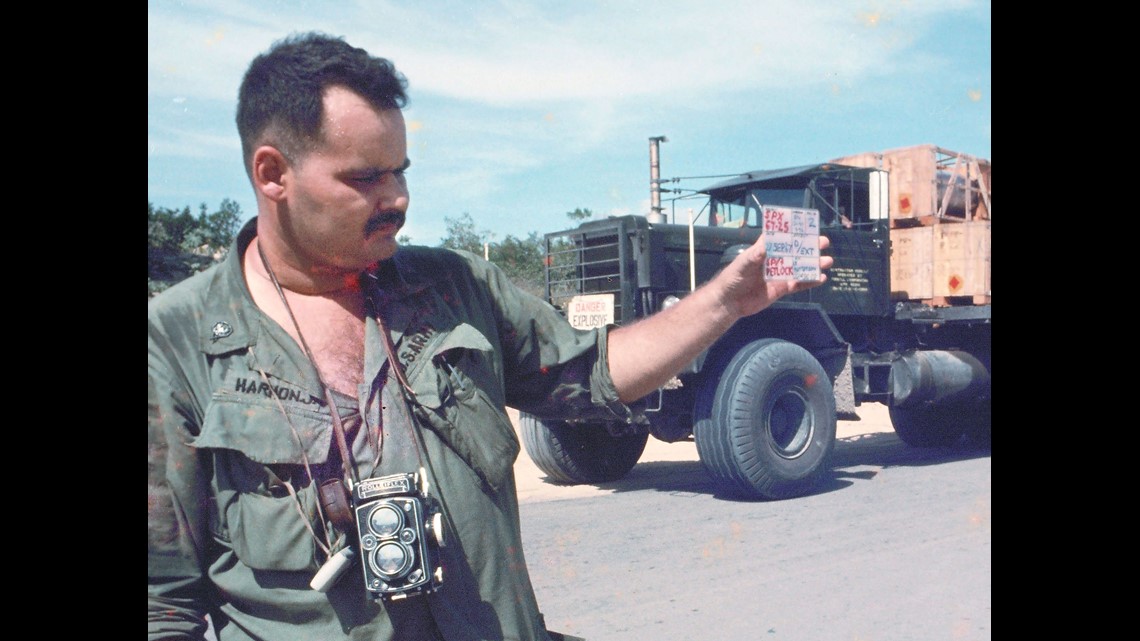

The Battle of Dak To

One final note on the valor of the 221st in combat situations While the combat photographer’s primary objective is to document the events of war, they are trained as infantry, armed and ready to fight if needed. At Dak To, they were needed as riflemen, to help transport the wounded, and to record one of the biggest battles of the war.

Dak To was 19 days of intense fighting in the jungle covered central highlands. Here, the North Vietnamese were dug into defensive positions on three hilltops and the U.S. and South Vietnamese were determined to push them out. The 221st distinguished itself at Dak To both as a fighting and photo force. From the unofficial unit 221st history:

“On 11 November 1967, three 221st photographers involved in the Battle of Dak To made the decision to carry on their photo mission. All three were wounded in the ensuing action. SP/6 Maurice Cauchi, SP/4 Michael R. Breshears, and SP/4 Charles Keneipp all distinguished themselves that day, disregarding heavy enemy fire to get first-hand coverage of the historical battle. Their OIC, LT Allen Patterson, opted for action, aiding the wounded, carrying ammunition and helping his team members to safety after they had been wounded by mortar and rocket fire. He is remembered as the man with no rank or insignia on his uniform, who while under fire, crawled out of his foxhole to help tend the many wounded of Hill 882, and remembered his original mission by calling down to SP/4 Breshears, ‘Do you need any more film,’ not knowing that Breshears had been wounded a few minutes earlier.

"On 18 November 1967, two more photographers involved in a later enemy encounter in the Dak To action, were caught with a land element beyond the defensive perimeter and were forced to drop their cameras and defend the lives of their host unit. SP4 James Thomas and SP5 James Newlin were wounded by incoming mortar and small arms fire. A third photographer, SP5 Jim Harmon put his camera aside and joined a rescue element. For his courage, he was recommended for the Silver Star.”

Harmon lives in Denver today and is disabled from Parkinson’s disease. His buddies in the 221st believe it’s the result of frequent exposure to the defoliation chemical Agent Orange. There’s evidence to support that claim and the Veterans Administration advises Korean and Vietnam era veterans that their exposure could lead to a host of other horrible afflictions.

“To direct, supervise and coordinate the performance of photographic and audio-visual functions in support of U.S. Army Elements and other Military and Governmental Activities in Southeast Asia – Mission of the 221st Signal Company (Pictorial)

Chapter index:

1. OVERVIEW

The world’s eyes have been drawn to war time photography for nearly 200 years. The first known pictures from a war zone are from the American-Mexican War in 1847, and were taken by a Mexican photographer. From that moment, the practice advanced quickly, according to the History of the U.S. Army Visual Information Center:

"The British sent Roger Fenton to cover the Crimea War in 1855, and the first military photography school was set up the next year in Chatham England. In 1860, a French minister of war demanded that one officer in each Army Corps gain photography expertise. Napoleon III even used aerial photography from balloons in 1859. But in the U.S., the War Department paid little heed to an 1861 American Photographic Society appeal for use of military photography. After all, a civil war was brewing. The first U.S. military photography was done by civilians like Mathew Brady and his staff of cameramen. President Lincoln himself penciled Brady a note giving him access to military areas. But Lincoln told Brady that he would have to pay his own way, without Government funding. Brady, his associates, and other civilian photographers documented all aspects of the Civil War."

Brady’s photos were displayed in his New York gallery allowing Americans to see firsthand the price of war. His images were either portraits of soldiers alive, or their dead bodies on battlefields. The impact was enormous.

Before the turn of the century, photography became a military duty assigned to the Army Signal Corps, and when technology advancements made cameras more portable and easier to use, the Corps developed labs and libraries to handle a growing product portfolio. From training films, to gathering battlefield intelligence using aerial cameras attached to balloons and planes, to still and motion pictures of the armies in the field, the never ending need to document activities became the responsibility of American military photographers. Just before World War II, a diverse bureaucracy of photo services consolidated into the Army Pictorial Services Division, Office of the Chief Signal Officer.

During World War II and into the Korean War scores of enlisted men became combat photographers, and along with some quite famous civilians, were embedded in operations around the globe. The work of W. Eugene Smith, Margaret Bourke-White, Dickey Chappelle, and Robert Capa, to name a few, was processed by the Army Pictorial Services Division and lasts to this day as a rich history of the so-called Greatest Generation’s successful effort to save the world.

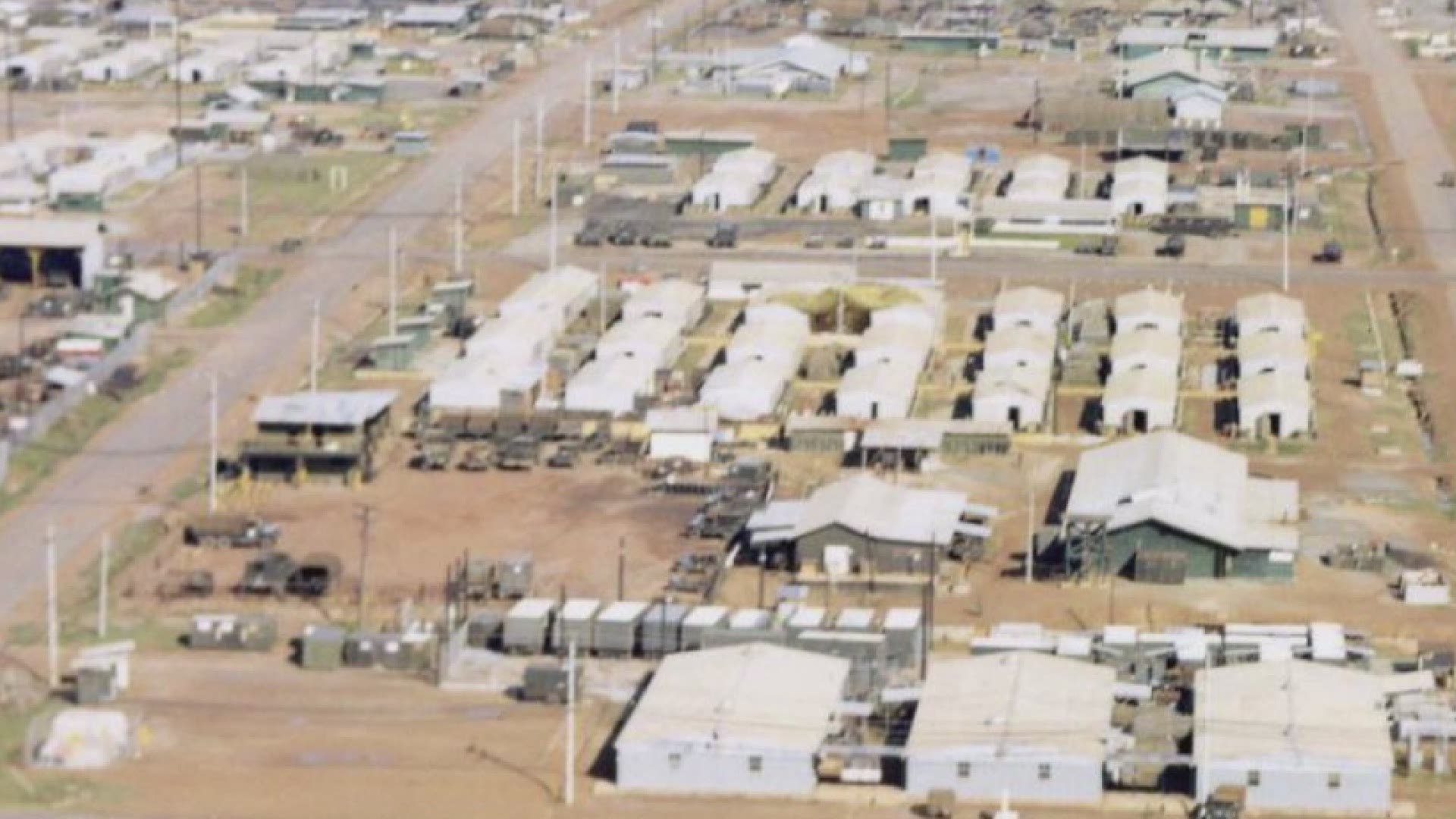

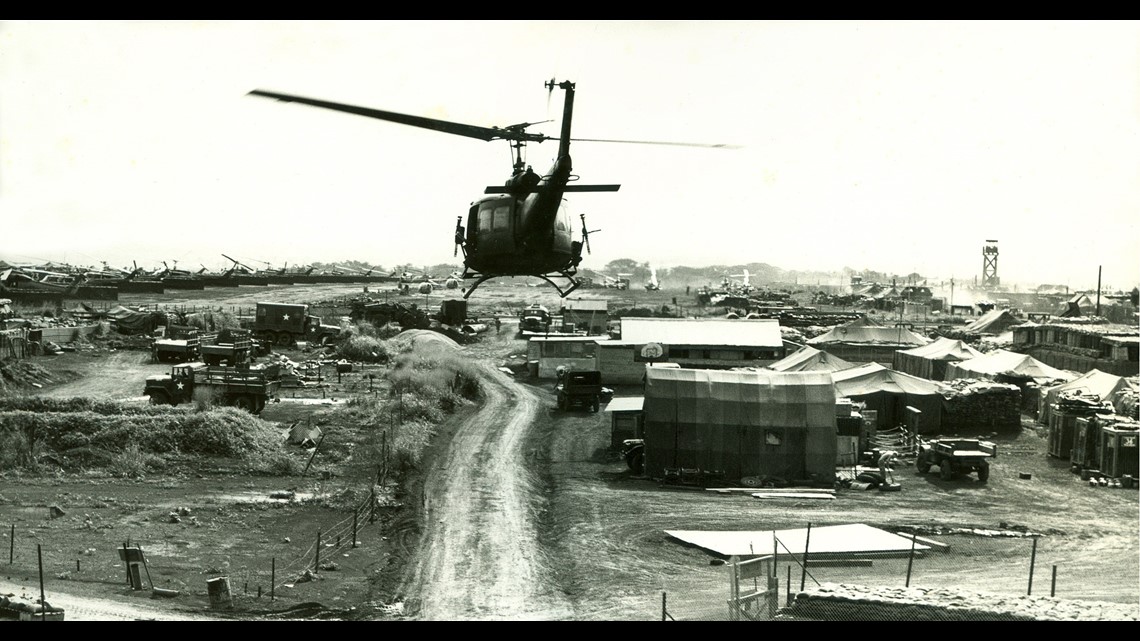

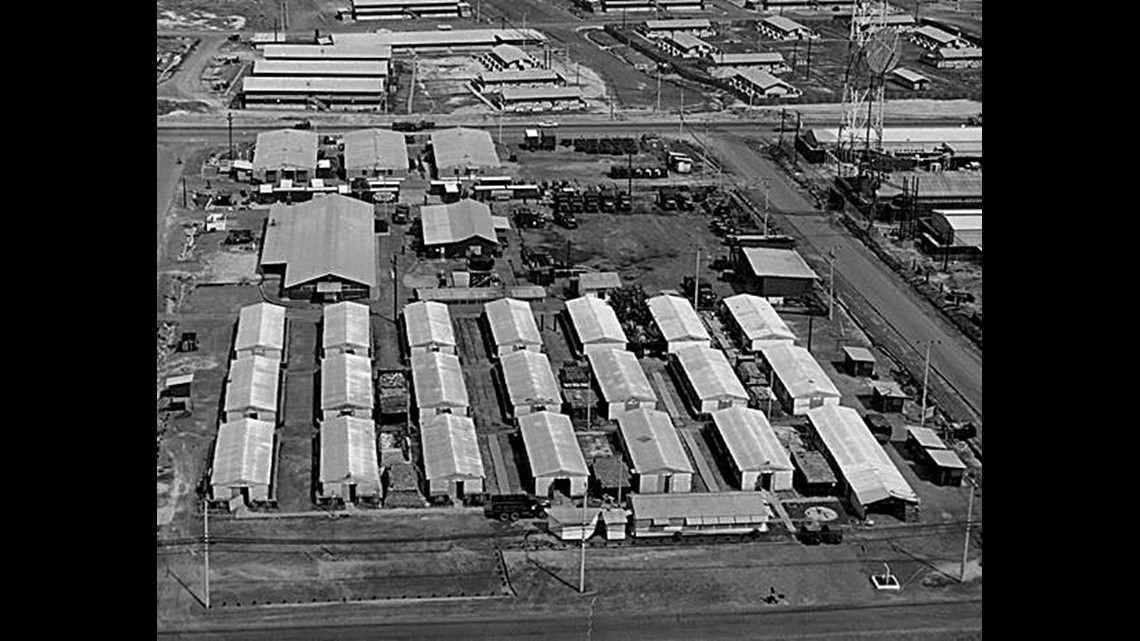

By the late 1960’s as the United States role was escalating in Vietnam, the Army felt the need to get photography units based in country. They chose the massive army installation at Long Binh, 20 miles north of what was then Saigon and is now Ho Chi Minh City. Given the assignment were the officers and enlisted men of the 221st Signal Company (Pictorial) and the Southeast Asia Pictorial Center (SEAPC), which initially acted as a mission-coordination liaison with major units, and later, became the supervising element in the 221st Signal Company chain of command. In effect, became the largest photo team in the war.

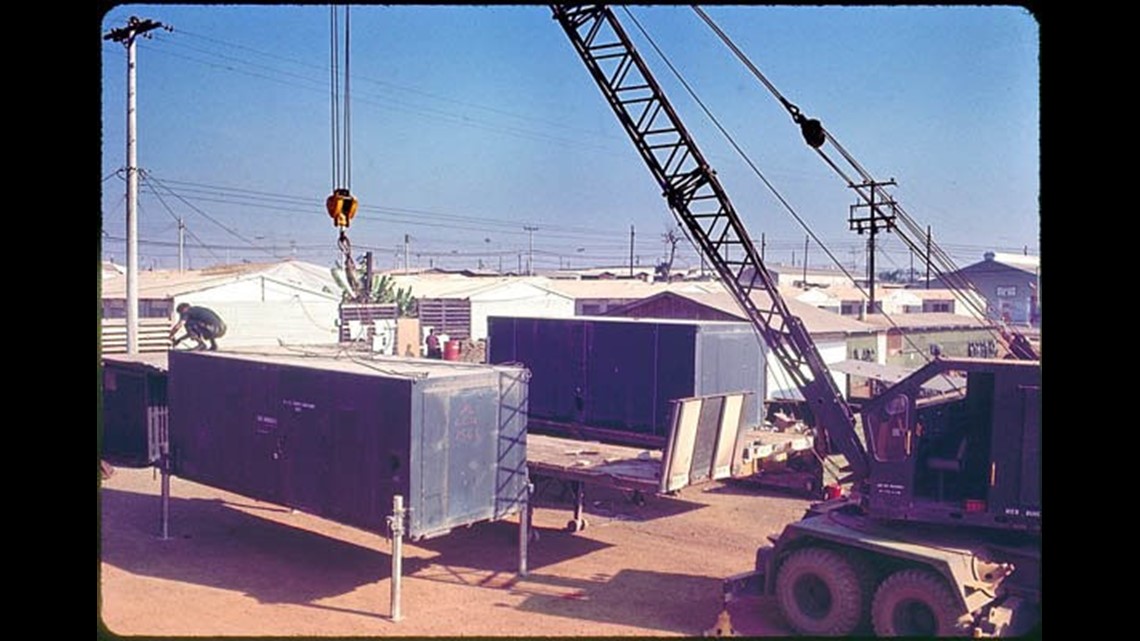

The 221st and SEAPC operated from a city-block-sized footprint of buildings that contained film-processing equipment, cataloguing, training rooms, maintenance shacks, dark rooms, and supply storage. The photographers arrived in country after basic training at Fort Gordon, Georgia, photo school at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, then assignments at the Army Pictorial Center on Long Island. The transition could be intense, but the 221st took care of their own.

Three members of the 221st have produced a history that will get the first wide circulation in excerpts here. The last commander of the unit, Captain Bill Ruth wrote the foundational piece with additional detail provided by 2nd Lt. Sonny Craven, a photo team leader, and 1st Lt. Frank Lepore Jr., who supervised the creation of the base headquarters facility in Long Binh. Here is their description of creating a base of operations and activating the first combat operations in South Vietnam:

The 221st was the Vietnam successor to the WWII, and Korean War Signal Corp photographic units. Army combat photographers were responsible for historical images by which we recall D-Day, Bastogne, Salerno, Anzio and during Operation Market Garden Holland. Speeches by great Army leaders, Patton, Eisenhower, MacArthur - are forever memorialized by cameras of these professionals.

221st History - Building the Base at Long Binh

Unit “packets” arrived in Vietnam by Navy ships in serials or "packets" before all its modern equipment had been delivered to the company headquarters at Fort Monmouth. Upon the first packet arrival in Long Binh, Vietnam, the small number of men acted as an advance element to prepare a base for follow-on packets. The company occupied an area equivalent to a large city block near the center of Long Binh Post. They faced major obstacle: there were no pre-prepared facilities for them, yet they began conducting limited operational missions while troops were living in tents in sweltering-heat. Facilities had to be constructed using manual labor and the primitive tools brought with them. They battled scorching hot weather and effects of anti-malaria pills (daily dose available at the mess hall, and affectionately called 'Brown Bombers', due to usual impact on Soldiers' alimentary tract).

They leveled a large expanse of ground made of tough laterite clay, mixed bags of concrete, and poured dozens of large pad foundations for big aluminum buildings we had to erect. No heavy equipment, engineer units or extra labor were available from the main base garrison to help build a base of operations.

The first camera teams were saddled with rusting equipment and durability weaknesses. They were untested in tropical humidity and frequent downpours. These problems frequently sidelined some equipment and rendered vital capabilities unusable.

221st History - Deploying throughout Vietnam

Unit members who followed-on from the original members, inherited a more mature, experienced unit with better living conditions, unit capabilities and improved personnel skills. They deployed a series of remote detachments as originally envisioned, and designed to rapidly respond to operational necessities in enemy-contested areas in proximity to military combat bases. The geographic diversity of the detachments helped to capture more high-quality action-oriented battle films.

In August 1968, the pictorial agency was re-designated the Southeast Asia Pictorial Center. Concurrently, men and equipment for photo support on a large scale began to arrive in Vietnam. This organization soon became the most extensive and complex photo facility the U.S. Army had ever placed in a combat zone. In addition to its central facilities at Long Binh, the pictorial center maintained and operated photo support units at Phu Bai, An Khe, Cam Ranh Bay, Can Tho, and Saigon. Each unit was capable of providing complete photographic service within its area of operation. The Southeast Asia Pictorial Center was the first Army photo facility to be capable of color processing and printing in a combat zone.

After little more than a year after the unit's establishment at Long Binh, detachments were set up in order to more efficiently handle DA photo requirements and to insure almost immediate coverage of any event. The detachments were located as follows:

1. Detachment "A" - Pleiku

2. Detachment "B" - Cam Ranh Bay

3. Detachment "C" - Saigon

4. Detachment "D" - Can Tho

5. Detachment "E" - Danang

6. Detachment "F" - Qui Nhon

7. Detachment "G" - Phu Bai

221st/SEAPC photographers have covered every major area and event in the Republic of Vietnam, including the Cambodian Expedition, Lam Son 719, the armed Forces Day Parade, the inaugurations of President Thieu, the South Vietnam president's Emancipation Proclamation signing granting full citizen equality to South Vietnam's Montagnard people, the Tet Offensive (1968), the A Shau Valley operations, Dewey Canyon II, even the Saigon Rock Festival. The coverage extends from dental and finance units to the combat assaults of the 101st Airborne, from the ARVN border battalions to the Thailand signal sites, from the ROK (South Korean) Tiger Division to Thailand’s elite "palace guard", the Royal Queen's Cobra Regiment, and medical air evacuations to Medical Civic Action Programs (MEDCAP). Indeed, virtually every aspect of the Vietnam conflict has been recorded on SEAPC footage and submitted for record to the Department of the Army.

221st History - Phasing Down

In October of 1971, the 221st/SEAPC organization began a slow phase down, but not before having earned the respect of every unit they assisted. In June 1970, the unit was recommended for a Meritorious Unit Commendation Award. The recommendation read in part:

“During the recommended period, the Southeast Asia Pictorial Center and the 221st Signal Company (Pictorial) made significant contributions to the pictorial documentation of United States and Free World Forces activities throughout the Republic of Vietnam. In so doing, they achieved an unparalleled submission and acceptance rate by Department of the Army for historical record negatives, the best in the world. The quality of the work submitted by assigned photographers has been outstanding. 221st photographers have been the recipients of the CSA Army Award for Outstanding photography twice. In addition, the motion picture footage obtained has been utilized by news media and in Army training films. The Military News Photographer of the Year Award was awarded to a member of the Army MACV motion picture team. Substantive recommendations have been submitted through channels to improve the MOS training of photographers, laboratory specialists, and repairmen. Many of these suggestions have been or will be incorporated into their courses.”

PHOTOS: May 9, 2016 reunion in Phoenix

“All the stuff that we did is going to frame the debate about Vietnam for the next 100 years, 200 years.”

Paul Berkowitz dropped into Vietnam in July of 1969, fresh out of film school, a ROTC commissioned 1st Lieutenant, an LA guy who wanted to make movies and got his chance in a war zone. “Peaches” as his wartime buddies know him was the self-described “odd one” in a family of produce grocers. They moved from snowy Cleveland to Southern California by the time he’d entered high school. Growing up near Hollywood got Peaches thinking about director’s cuts and starlets, not raisins and avocados, so he skipped the family business and headed for UCLA.

Chapter index:

1. OVERVIEW

That his plan would be interrupted by Vietnam was a certainty, though Peaches took steps to hold off the inevitable, including grad school. But to stay in school, he was obliged to join a two-year ROTC program to stay in school hoping that the war would be over before his graduation. It wasn’t, so he found himself in country as part of the 221st Photo, the largest unit of its kind in Vietnam. It wasn’t the path he’d have chosen, but in the end it worked out.

“That’s what I wanted to do,” Peaches told 12 News, sitting at the 221st reunion he helps organize every year. “I didn’t really like the war. I wasn’t in favor of the war to be honest with you. But, I wasn’t going to shirk my duty either.”

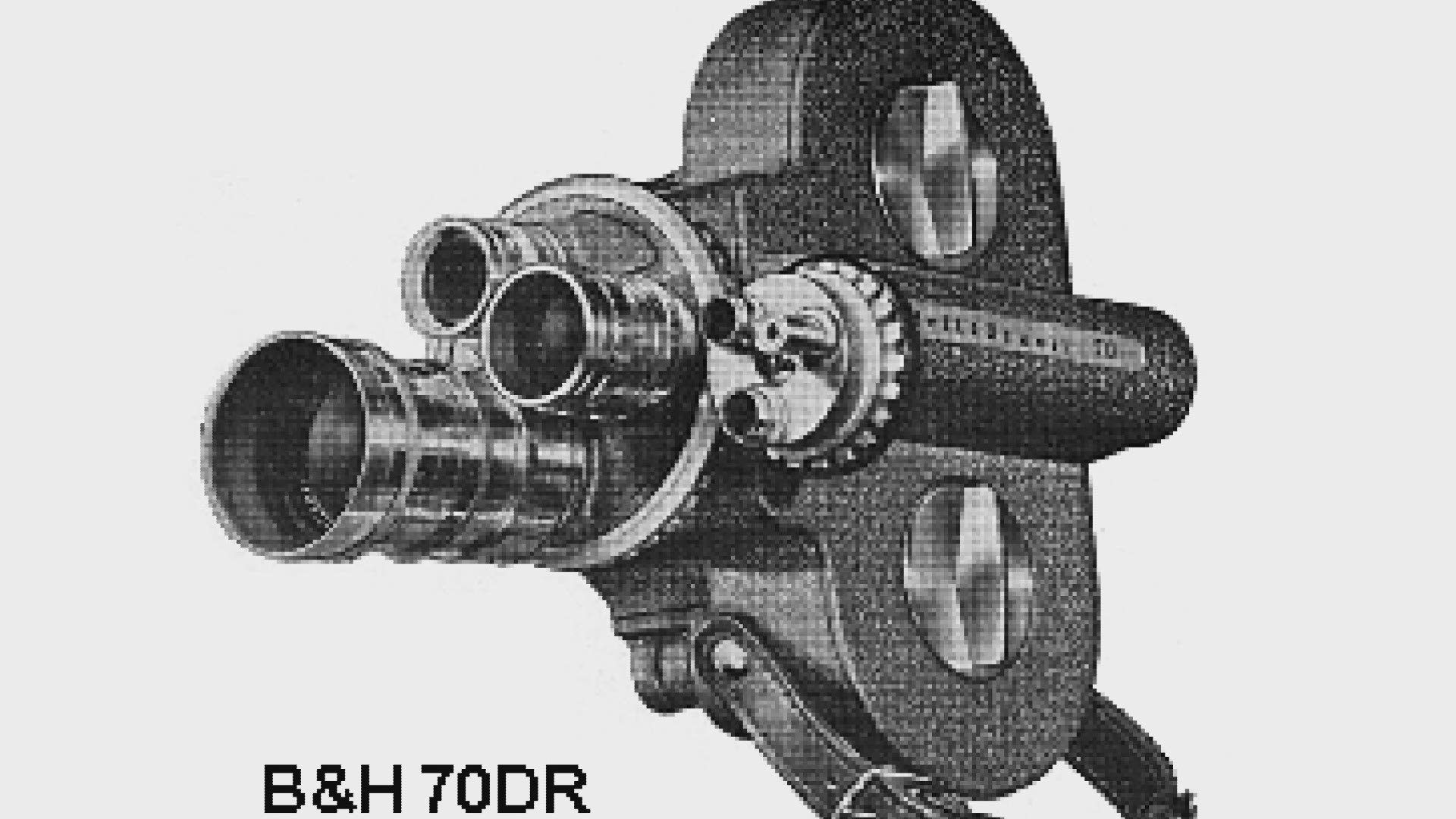

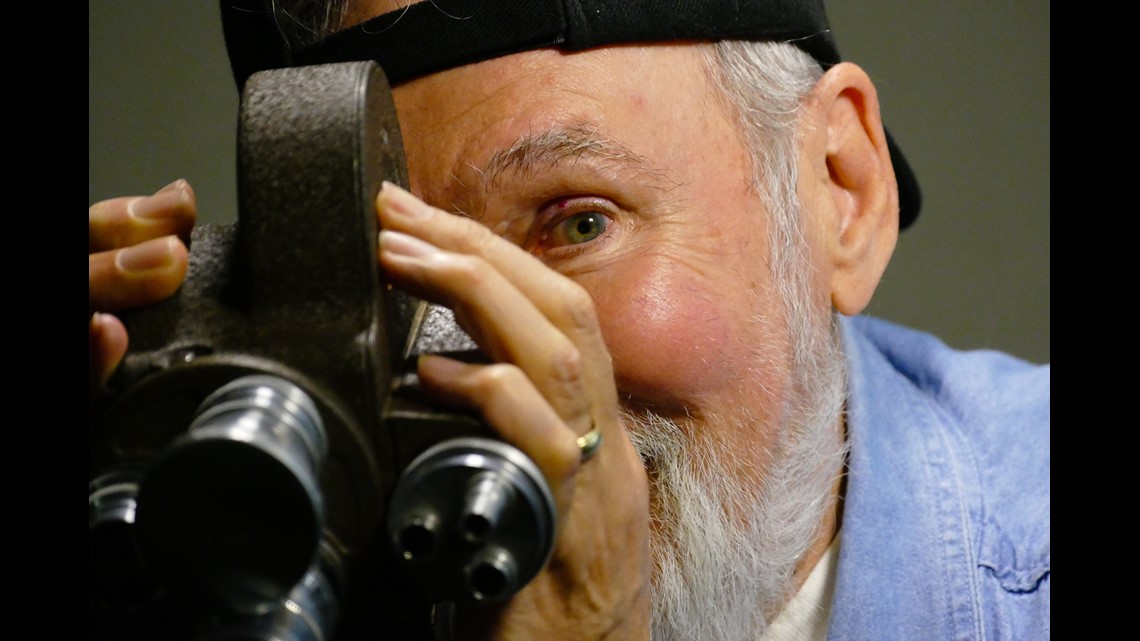

While at UCLA Film School, Peaches had used state of the art film and video equipment to produce finished product for showings on Public Television – now he was faced with aging Army equipment. The primary Motion Picture camera was the 16mm Bell and Howell Filmo, a wind-up hand cranked camera with a three lens turret. It was portable and tough, designed for silent combat photography. For sound on film, the Army initially choose for Vietnam a new camera from Beckman-Whitley, the CM16. It was a disappointment to say the least. Later on it approved a limited number of higher end Arriflex production models. These were in high demand by Army MoPic men, including Peaches.

Hand cranks? Silent film? Three lens turret? Obviously, this was not iPhone or Droid point, shoot, post.

Our interview was wide-ranging and Peaches was generous with his time and memories of his tour in Vietnam, from July 1969 to March 1970. Here are five takeaways:

Number one - there was no “normal” day for the 221st. The work could be mind-numbingly boring, like assignments shooting Signal sites. Mostly, whether of combat or otherwise, MoPic footage went back to the states without anyone knowing how it might be used – purely historical record. Then came an assignment that shook things up just a little bit for Peaches and his fellow team leader Pete Berlin.

“… drew the assignment to make a recruiting film for the Army Audit Agency. It was no surprise that Army Auditors, all civilians, wanted no part of the war zone. The film was meant to allay their fears. It was a rare chance to do a complete production in-country, from shooting to final edit. “

The shoot was also memorable because they used high end Moviola editing gear for the assignment.

Number two - the work could also save lives. Nighttime at the U.S. bases was combat time for the North Vietnamese, who somehow were able to quietly squeeze through tiny spaces in the camps’ barbed wire perimeter and attack. Peaches worked with North Vietnamese defectors, called Chieu Hoi, to create a video explaining how the lines were breached.

Number three - the work could be a total adrenaline rush. Peaches didn’t take enormous risks but his buddies did, finding their way into intense combat armed with…a camera:

Number four - you established deep relationships and made lifelong friends. Your tour was literally life threatening and your support system was nearby. The camaraderie was important – and it was one of the reasons that Berkowitz became “Peaches,” a nickname stolen from a female tennis star of the era named Jane “Peaches” Bartkowicz.

“I was Berkowitz, that was close enough to Bartkowicz for Bob Fulstone who pegged me with the name and it stuck. I retaliated with Flintstone which stuck to him. It was no use trying to duck a nickname – only made it worse.”

Number five - 50 years later, the work is still significant. Vietnam was one of the most documented wars in U.S. history. The 221st was assigned the official history but the news media was given almost unlimited access to the theater. Besides being striking, provocative, and visual art, the images teach.

PHOTOS: Cameras in the field

“There is only one thing to do and you just got to get down and do what you do, and that’s it.”

Our military is interwoven with our country’s history. Those who endeavor to be a history-maker are drawn to the structured ranks of our armed services. The same goes for those who want to write it, photograph it or capture it into motion picture to live on through time. During the Vietnam War, these men fell in step with the 221st Signal Company (Pictorial).

“I always wanted to be a photographer because I always figured the Army was going to do something historical, and I wanted to be there when it happened,” Mike Boggs said. He was a combat photographer in Vietnam. Boggs served with the 221st at the height of the unpopular war.

Chapter index:

1. OVERVIEW

The combat photographer “figured” correctly about finding “something historical” in uniform. His years of service before arriving in Vietnam already providing opportunities to see through a lens the likes of John F. Kennedy in Berlin, to Chiang Kai-shek inspecting Taiwanese troops, and onto underground nuclear testing in Nevada. While capturing history, the young serviceman couldn’t have ever appreciated he was now a part of it – the part found in color or black and white or the parts now viewed on the History Channel.

The tall farmer speaks about these moments in time as easily and as he does his bird-dog who keeps him company on his Illinois farm. The chaos of the Tet Offensive is delivered with the same emotion as recalling what crops he chooses to grow. But humor is different. Boggs delivers it with the same quickness and ease that he clicks the shutter. His emotionally camouflaged demeanor cracks for the good times. His first day in country was the first time he smiled as he sat with 12 News.

“We wound up in the supply hooch and we were all drunk as skunks,” Boggs smiled on as he spoke. But the morning brought sobriety and war. Boggs had history to attend to.

Combat photography in Vietnam needed guys like Boggs. The constant dangers were just as a real for a uniform shooting a gun as the one shooting a Nikon. The miles walked in jungle boots were just as long for an infantryman as a cameraman. The landmines or spray from an AK-47 threatened all equally. But Boggs and his buddies from the 221st kept to their duties to document the stories and reveal in images the intelligence gathered from reels of film. To them their mission and results of their duties were simple.

On those days Boggs learned to be apathetic to stress. He learned to hide his emotion or fears when gunfire erupted. He sought refuge in the very tool that attracted him to the danger.

“A lot of times you crawl into the lens. And you sort of get in there and feel invisible because you are inside this lens," he said.

The political temperature in Vietnam left him no safer than if he wasn’t looking at it through a viewfinder. But it provided a filter to keep him from fully acknowledging his surroundings.

“Of course we were young and stupid and cowboys and everything else over there. So nothing was going to hurt us. It was all fun and games until someone got hurt. Then you went from there.”

Boggs left the warzone for home where he first learned his work wasn’t ready to be appreciated yet.

Boggs spoke again with no emotion. He held no feelings of animosity for not being welcomed home by the Americans he was serving.

“We had somebody took a sling shot and put a bolt through our window. It not only went through the window but the plastic window shades behind it. And we were told to check our vehicles for bombs.”

This was the part of history that was still being written that Boggs didn’t know. He said what college students stateside were doing while he was fighting a war never came up on the battlefield. The rude awakening would have been a shock if Boggs was capable of the emotion. Instead, He smiled as he reeled in for another memory and chuckle.

“One time I was on recruiting duty and everybody was burning their draft cards. So me and this Sgt. Hickman we put a sign in the window that said ‘let us burn your draft card’. The next morning I heard supervisors down there about ready to tear the window out.”

Boggs' legacy wasn’t written in Illinois though. His butt was chewed there for his sense of humor and draft card stunt, as he put it. But his life story will always be back in Vietnam. He and the rest of the 221st now relive it through the images they see in history books or the multitude of military channels offered on cable TV. They captured it. His service to country was used so those of us who weren’t there can still see and feel what it was like when they were. It’s how we know. It’s how history is told. And that’s all Boggs ever wanted.

“I got to be at a lot of historical places,” Boggs said as his faced crooked into a smile for one more zinger.

“Come to find out when you’ve been at historical places – It’s hot and your feet hurt and sometimes your back hurts,” and he laughed just enough to redden his cheeks.

His next line delivered back in the monotone he learned somewhere in Southeast Asia returned.

“Everyone is going to look 500 years from now and say ‘that was a historical event.’”

“I never ask anybody to do something that I was not willing to do personally myself. So I took some jobs as well …”

Chapter index:

1. OVERVIEW

In a patch of the swampy jungles of Vietnam, the wet foliage was bulldozed and prepped for history. It would be the base camp from where the controversial Vietnam War would be documented through images. The visual link between then and now was forever captured in film and still photography by the soldiers of the 221st Signal Company (Pictorial).

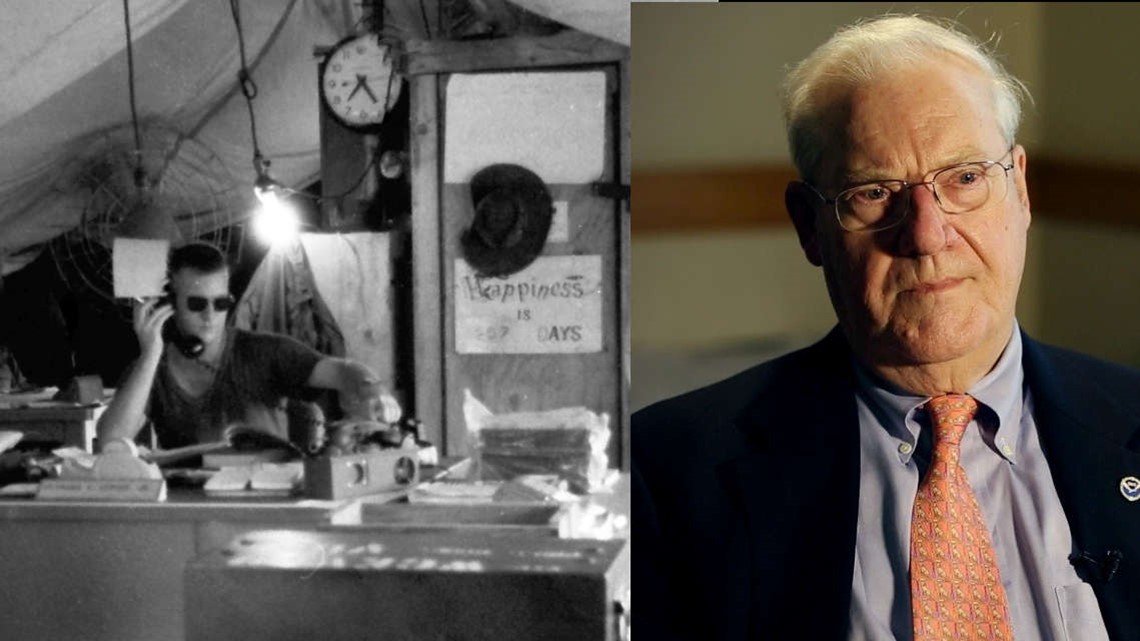

“We were the advanced party. We were supposed to get there and set up operations and prepare for the follow on units to come,” said Lieutenant Colonel (Ret.) Frank Lepore.

At the time a lieutenant, Lepore was one of the first in country of the combat photographers who made up the 221st. He was also the man responsible for making sure those photographers had cameras, film, chemicals and infrastructure to make sure history could be captured through a lens.

The Army, at the advisement of Lepore, literally sent a shipload of Conex containers filled with photographic and film camera equipment to Southeast Asia in 1966. There 44 men awaited the arrival of their cameras so they could begin their mission.

“We are talking about everything from cameras to tractor trailer loads of film that had to be put someplace out of rain,” Lepore said. “Otherwise it was going to spoil.”

Before film could roll or shutters fire, the base had to be build. And it was the job of photographers to trade film reels for hammers and build their studios and barracks. The greatest challenge of all was the weather. For most of the soldiers, this would be their first concrete pour in a jungle with the monsoon unloading amounts of rain none of these Americans were accustomed to.

“They all looked at the vacant field at the same time and said ‘Ah, this is not good.’ And I knew it was really not a good situation because I had just planned to send literally a ship-load of stuff behind us,” Lepore said. “They all realized they had to pitch in, officers and men alike, actually building an encampment for those that would follow. They did this without grumbling.”

This advanced party would shoot images by day and pour concrete at night under the lights of jeeps.

“It’s one of those situations where it’s a bad situation to start. But a bunch of people come to the same simultaneous conclusion that we got to make this good. And good people make it happen.”

Eventually their base was built. In total their photo studios and support structures took up the equivalent of a large city block. Lepore, acting as the forward deployed “detachment commander,” turned his focus to capturing history. It was his job to send others to missions which would naturally put them in the middle of firefights as they captured historical photography and gathered intelligence through imagery. He performed the duty ultimately of pointing to a hill and instead of saying ‘take it’: He’d ask his soldier’s to photograph it while trying to stay alive.

Knowing he couldn’t lead without understanding the conditions his men worked in, Lepore too captured images that became part of our country’s history.

“I never ask anybody to do something that I was not willing to do personally myself. So I took some jobs as well," he said. "See you can’t really effectively lead unless you’ve followed and been able to do what they do… know what their hardship is… know what they need to do the job.”

Side by side in war these photographers formed keen friendships. They often crossed lenses with their civilian counterparts who were there to report on the war. The history of civilian correspondents was not new, but it was the access to war that was evolving. Vietnam was an early look at what it would eventually be like for journalist to fully embed with military units. It would was the beginning of what can be a rocky relationship at times. Material shot by a civilian film crew in country would ship their film off to be written and edited back in the States.

The result sometimes led to confusion for those at home. “When folks are sitting at home and flip on the six o’clock news – there reality is the reality they are seeing on that little TV tube.” But that reality was often written and edited by someone who’d never stepped outside of a New York or San Francisco television studio.

With the benefit of hindsight and being responsible for capturing history, would Lepore have changed the way it was all written?

Those lessons are now forever in the film we watch and pictures we click on when we want to learn about the Vietnam War. History captured by Lepore and his fellow combat photographers.

“Eighty-percent of the information we perceive is visual. Visuals are a very good way of communicating that (history).”

“I have no animosity toward the enemy. I didn’t have an enemy. I was there pointing my camera at what was going on around me and didn’t have too much of a preconceived notion of who would be an enemy” - Roger Hawkins

Chapter index:

1. OVERVIEW

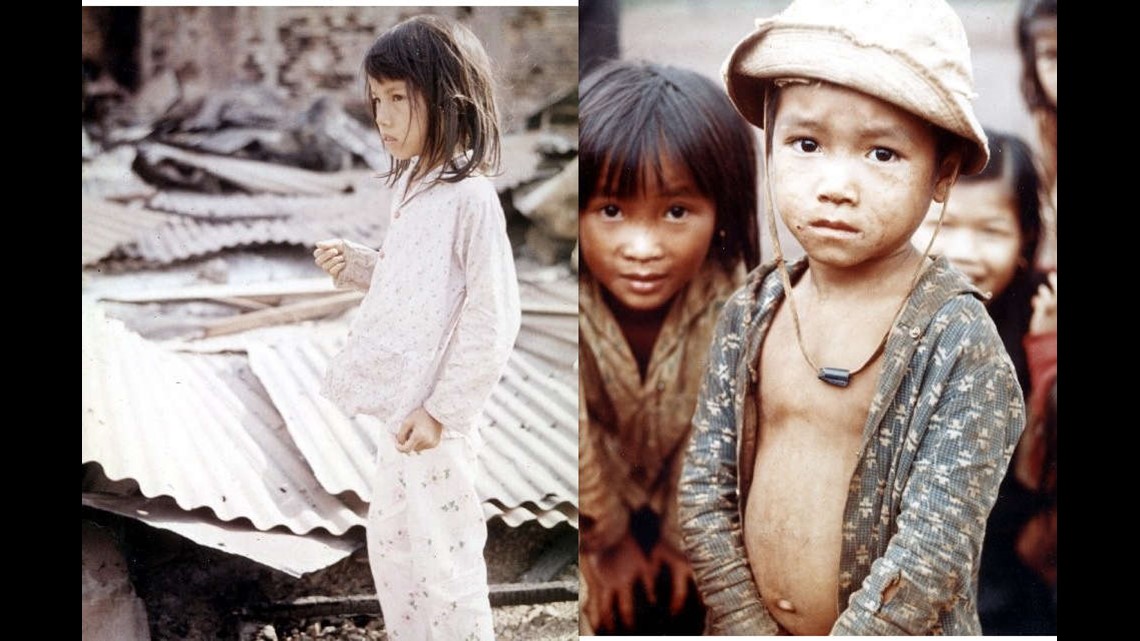

Nations go to war, and inevitably, civilians suffer. The war in Vietnam was no different. Caught between the armies of North Vietnam and the United States, the South Vietnamese people tried to stay alive balancing the potentially lethal competing interests of what many of them saw as two invading armies plus an enemy within.

Consider this. You’re a rural villager in South Vietnam. A platoon of American soldiers arrives at your home, looking for North Vietnamese sympathizers. They’re heavily armed foreigners trying to stay alive and determined to complete the day’s mission. You do what you can to appease them. Your children, curious about these men, run and play around them, even hanging on their arms to tease them. Some of the GI’s are amused. Others are tense and distrusting. The Americans leave without incident. You are relieved.

Later that same day, another armed group shows up, this time from the National Liberation Front, more commonly known as the Viet Cong. These are guerrilla fighters supporting the North Vietnamese, who one moment are sniping at American GI’s with an AK-47, and the next are weaponless, standing in the paddies cultivating rice. You may even know one or two of them because they once lived in your village. They want the same things the Americans wanted. You need them to leave without hurting your family, so you tell them the Americans have been here and gone, pointing the direction the platoon took on its way out. They raid your food storage, then move away without any incident. You feel violated, but fortunate to escape unhurt.

Mike Boggs was embedded with combat units and saw the conflicted lives of the Vietnamese peasant.

Often, these two different groups of warriors did not just walk away. Sometimes they burned villages and murdered their inhabitants. Other civilians were victims of aerial bombings, shelling, or assaulting troops from both sides. Researchers at Harvard University and the University of Washington estimate that 2 million Vietnamese civilians lost their lives. An exhaustive investigative work by journalist Nick Turse, entitled Kill Anything That Moves lays out the atrocities in hideous detail.

In war time, state sanctioned murder of innocent civilians is, at best, a tactic designed to squeeze an enemy so hard that they surrender. At worst, it is racist genocide conducted by military and civilian leaders driven to eliminate, at all costs, an opponent who they’ve labeled as evil, subhuman and unworthy of living. Clearly, both the best and worst case approaches were at work in Vietnam on both the North Vietnamese and U.S. sides. The resulting loss of civilian lives was a heavy burden for the GI’s returning home. The actions against civilians have long been an open wound and often, the American soldier who did not harm non-combatants was tagged by an emotional and misinformed public with the same charges rightfully aimed at those who did horrible things.

The 221st committed no atrocities. They did witness the terrible results of combat and they interacted with civilians in less stressful situations. The limited portfolio of civilian photos provided by the 221st for this report is rich with images of children. A couple of boys strike tough guy poses, cigars in mouth. Kids peer through camera eyepieces with their uniformed new friends nearby. GI’s playing with the children, holding hands walking through the base. Roger Hawkins remembers how their obsession with the hair on his arms may have saved his life.

There are haunting images of children as well. Second Lieutenant Sonny Craven photographed two. He was one of the Photo Team Leaders with the 221st who rose to the rank of Colonel went on to a career with Armed Forced Networks. The first is a small girl in her pajamas standing on a roadside in shock, her village destroyed during the Tet Offensive and her parents missing. Sonny’s memories 50 years later are clear.

“The little village is Ben Hoa, and was nearby to an ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam) joint Army and U.S. Air Force base. The reason the village was attacked by U.S. helicopters was evidence that showed VC sappers who blew the fence wire to get to the airplanes in protective revetments lived, slept in the village, then retreated back there for cover and safety. My memory is fuzzy, but I think 37-38 aircraft were blown in place in a hours-long attack across the base.”

The child’s image and that long ago day are still fresh for Sonny and he is emotional in describing it. He wanted to rescue that child and find her parents, but knew they’d probably been killed in the fighting. His unit moved on and the child remained amidst the destruction. The 221st team saw a lot of destruction that day. They were the only official photographers permitted in the combat zone on the highway between Long Binh and Saigon.

A second Craven image is the dirt-smeared face of a young boy.

“He was child of a Chieu Hoi. Chieu Hoi’, pronounced as chew-hoe-ey,’ explains Sonny. “It is a combination of two verbs ‘to welcome’ and ‘to return,’ and was an amnesty program for former Viet Cong.”

His father was likely undergoing indoctrination at the time. Dad’s in the custody of the South Vietnamese and the child is waiting for him to return. It must have been terrifying.

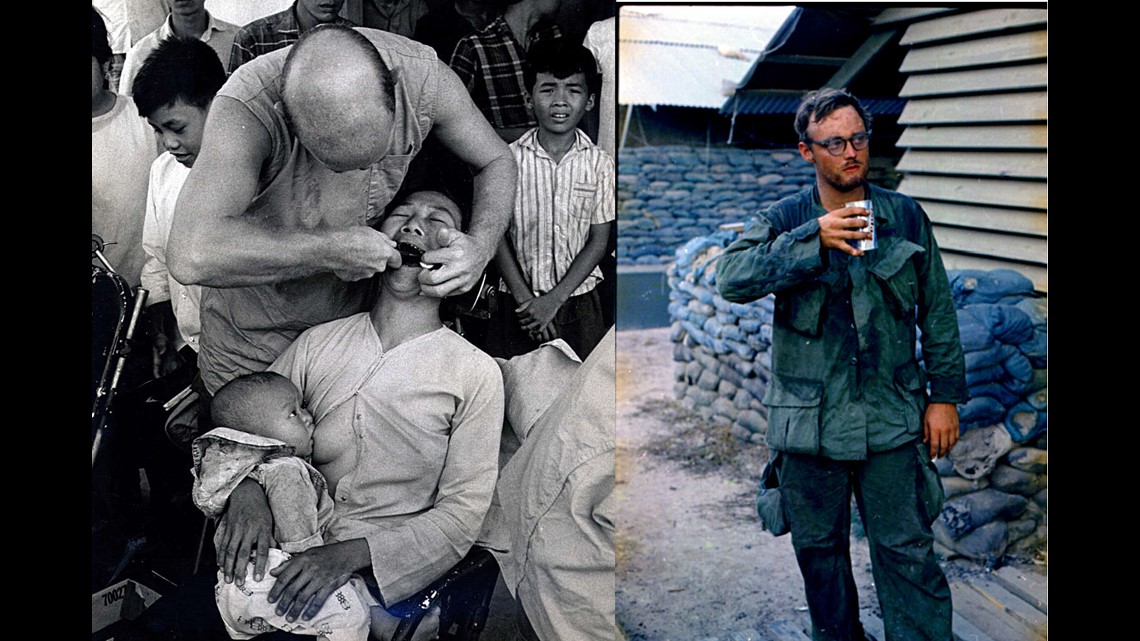

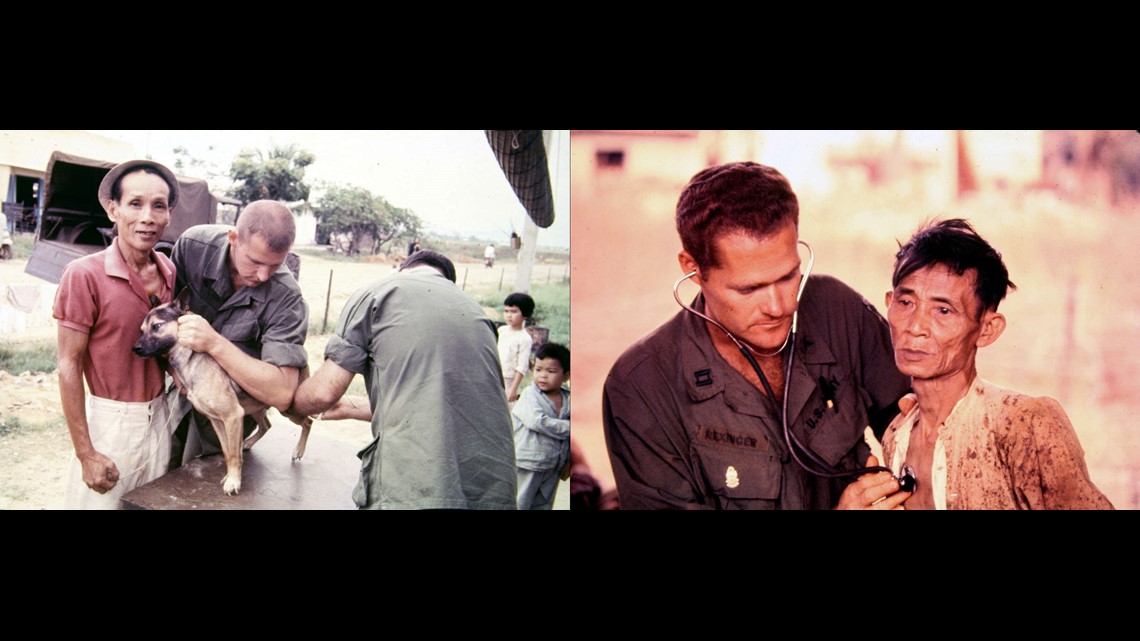

The 221st snapped hundreds of images of field medical staff attending to soldiers, civilians and animals. The field hospitals not only treated the wounded but also took care of basic medical needs for rural Vietnamese who, like rural people everywhere, lack care for the basics.

Here’s one that needs no explanation, a contrast of pain and nurturing

221st still photographer, Specialist 5 Glen Vehring made the photo. We won’t know the circumstances because Vehring died in 1985.

1st Lt Peter Berlin saw scenes like this often when he was assigned to document co-called “Civic Action Projects” designed to win the hearts and minds of the Vietnamese people. U.S. medical teams went into rural villages to provide people care and also animal care. Veterinarians who worked on war dogs most of the time assisted with family pets. Berlin remembers the medical teams as cool under fire whether dealing with combat or civilian maladies.

“Doctors, dentist and nurses preformed their duties in hospitals much the way they did at home," Berlin said. "They were constantly busy with combat wounds, but they also took care of colds, sexually transmitted disease, over dose, stomach aches and tooth aches, along with other things that normally happen to people. I never saw any usual signs of stress on the ‘medical’ soldiers. They did their job and they did it well and they returned home from Vietnam just like the rest of us, and in most cases pursued their career just we non-medical GI’s also did.”

Fast forward across the decades from the late 1960s to 2016. Paul Berkowitz, the 221st Pictorial Lieutenant from California left Vietnam 45 years ago and today still finds himself amongst the Vietnamese. Thousands of refugees settled in Los Angeles starting in 1975. Now, they’re his neighbors. He shops at their businesses. He sees them thriving in America, and is proud.

“It does make me feel good. And, I have been back to Vietnam, and I was sad the whole time I was there. Though in the South, there’s still a lot of good feelings for Americans. They want tourist dollars and all that. I didn’t go to the North. I don’t think I was ready for that.”

While in Vietnam, his contact with civilians was minimal. A laundress and maid they called “mamasan” – a term American soldiers used for any older Vietnamese woman - did domestic duties at their base, was trusted and liked. Paul did spend time with South Vietnamese soldiers and thinks about what must have happened to them when the North Vietnamese won the war.

Mike Boggs made friends with Vietnamese and remembers them as good people.

“Now the ones you got to know were very nice people. Matter of fact the Vietnamese people are very hearty, and in my opinion strong and brave individuals, but they were stuck between a rock and a hard place”

Mike’s memories of the Vietnamese have contrasts that exemplify an odd relationship - sometimes comedic and often very serious.

“We had the mamasans that were there in the barracks. Every time mamasan started going around looking under beds and stuff, everybody’d go bananas because we knew she’d hid her pot someplace and we didn’t want to get caught with it. You’d have a whole barracks looking for this little bowl of marijuana because we knew mamasan had hid it someplace, she’d gotten high and forgotten where she’d put it. And then, of course, we’d run into them in the field. Those people looked at us skeptically because we’d shot at them, bombed their villages and everything else. But you tried to help them, you know.”

In the end, the 221st did much to assist the Vietnamese civilians. From the group’s unofficial history:

“…members of the unit have repeatedly undertaken their own independent goodwill visits to orphanages and schools, contributing clothing, toys, food and small gifts to the Vietnamese children.

"The SEAPC detachment in Pleiku has established a working friendship with members of the several Montagnard villages in the area."

"During the Vietnamese Tet, the unit holds all day party for all Vietnamese employees. Families of the Employees attend, entertainment and refreshments are provided, humorous skits are performed, and good cheer in general abounds. The employees are awarded a cash bonus, and small gifts are often exchanged. The annual Tet Celebration is looked forward to all year.”

The challenges of being a combat photographer in Vietnam were extensive.

Chapter index:

1. OVERVIEW

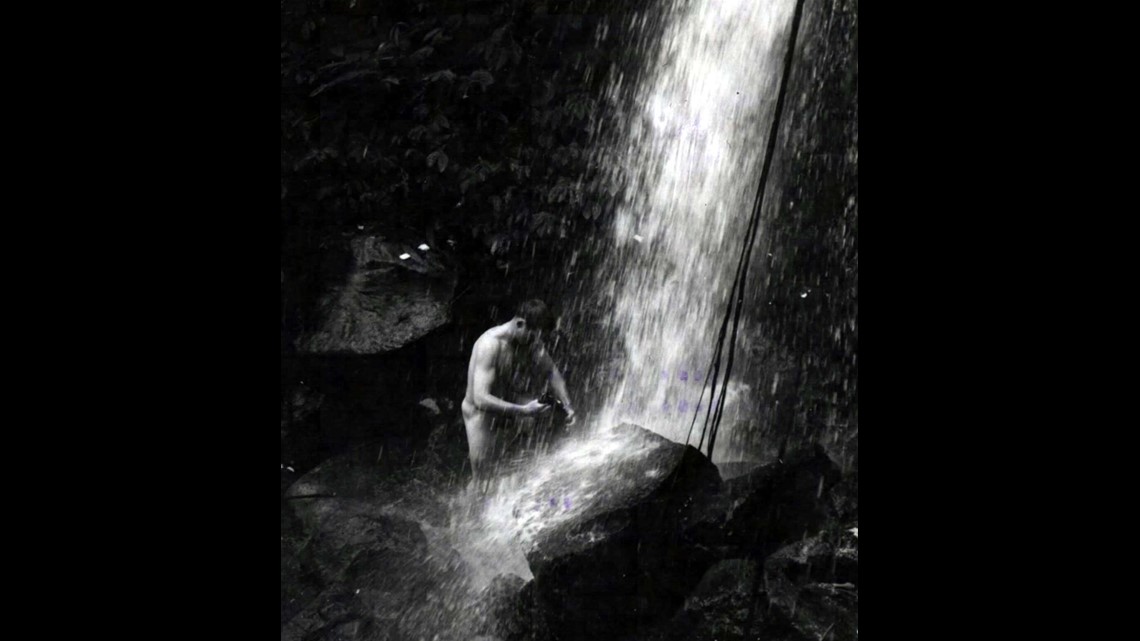

The terrain was unlike any most U.S. soldiers had experienced. That challenge remained for the photography equipment. Vietnam is known for its jungles and wetlands. The country is full of foreboding rivers and streams, rice paddies, and temperatures that regularly reached more than 100 degrees with nearly 100% humidity. If you add in monsoon season drenching your body and equipment, you begin to get the picture of being a photographer at war in Vietnam. If your camera was protected, it could survive. The same could not be said for film stock emulsion – the film used for motion pictures. It never stood a lasting chance. The footage that exist is a fraction of what was actually shot. This was the daily battle for combat photographers of the 221st Signal Company (Pictorial) who were tasked with capturing the war through imagery.

Deployed in Teams a field photographic team was made up of one still and one MOPIC (motion picture) photographer or two MOPICs and one still photographer. This basic setup could be modified to meet specific photographic requirements.

The mission of the 221st, even with the challenge of environment, was extensive.

- Still and motion picture photography

- Film development and print processing.

- Audio-visual equipment and training operations

- Graphic arts support

- Capture combat and field operations for use by Department of the Army

- Tactical, intelligence gather, and logistical photography for local commanders

- Information photography and historical record

The equipment the photographers used varied year by year. The start of the war was uncharted territory for not just the people but the cameras. The equipment had never been field tested for a war or the weather the equipment battled. The learning curve was stiff and unforgiving. As anyone who’s tried capturing the essence of a moment knows – there is no second chance when shooting history.

Here’s a snapshot of still equipment

- Leica rangefinder – Arguably the camera that made ‘35 mm’ the 1960s version of viral. The camera was widely popular and built to last. You could pick one up at a used store today, and it would probably still work. By 1969-70 timeframe, there was only one Leica remaining in the 221st photo equipment’s inventory.

- Graflex XL 98 – The last camera built by the company who built the original press camera. The XL 98 WAS used extensively by 221st Photographers.

- 4 x 5 Speed Graflex - Bulky, heavy and difficult to use in the field. Pictures of exception quality due to the large negative size. Many 221st Still photographers loved the results and so put up with the difficulties.

- Beseler Topcon Super D - professional grad 35mm SLR point and shoot that had a comprehensive range of accessories available. It came with a three lens kit. It had two major problems: the lens fell off the camera too easily and the shutter was very loud. Hardly anyone used this camera.

- Beseler Auto 100 - Flimsy in comparison to its counter parts, the Auto 100 was one of the first fully automatic SLRs. It didn’t hold up in the field but ran just $160.

- Nikon F – It was Nikon’s first SLR. The Army did not issue them however. Most of the 221st still photogs used their own.

Here are a few popular motion picture cameras

- Beckman-Whitley CM16 (16mm) - Without any doubt this camera was universally disliked by 221st MoPic photographers of all eras. This is why we acquired Arriflex cameras later on. The CM16 would not run consistently due to many design problems. It jammed easily. The single system sound was always problematic. The principal advantage of the camera was its excellent 12-120mm zoom lens.

- Bell and Howell Filmo (16mm) – Silent camera that shot on 100’ spools of daylight load film. It was a hand crank spring wind up. It was equipped with three fixed focus lens on a turret with glass viewfinders that made parallax a constant problem. But it was durable and ruggedly built and rarely failed in the field. It was standard equipment for U.S. military combat cameramen from World War II thru Vietnam. Almost all 221st MoPic men were trained on and used this camera.

- Arriflex 16S and BL (16mm) –Very popular 16mm production camera that could handle 100 and 400 foot loads. It carried a 12-120mm Angienux zoom, some motorized for smooth zooming. The BL model had a blimp for quiet operation and double system sound production. In short supply, this was the preferred and sought after camera for 221st MoPIc photographers.

- Dynalens - The 221st had a Dynalens in Long Binh. The Dynalens was a state-of-the-art stabilization aid that worked well with the Arriflex camera. The Dynalens was bulky and difficult to setup but it gave great results when shooting from a helicopter. The Dynalens had won an Academy Award for technical achievement in 1969.

No matter your camera of choice or lack of choices, the only guarantee the equipment had was that they were going to take a beating. The environment of a sub-tropical, heavily-photographic war meant there would be issues. Acquiring spare parts for both nonstandard and standard equipment was nearly impossible to ship into a worn torn country. There was never enough room to store the footage either. Storage also meant a high casualty rate for the film and equipment. All this of course paled in comparison to the bullets that chased you while you tried to capture history.

“For me the challenge of combat photography was splitting my concentration between the artistic and technical challenge of photography and the need to pay attention to survival,” said Roger Hawkins who served with the 221st as both a still photographer and motion picture photographer.

Hawkins said it’s been mentioned by several of the photogs that looking through the viewfinder gave the illusion of living in a little black room where no one could see you and you felt invincible. Of course that is an illusion and an illusion that could get you killed.

Unlike today’s digital age, you need to understand there was no instant gratification in capturing an image. If you believe you captured the perfect picture, well you had to wait to find out if you really had. The 221st was able to process both black and white as well as color film, but it obviously wasn’t done in the field but back at camp. This meant that with time and a little more work, you could at least see what you shot. For the motion picture shooter, the film was shipped back to the states to get processed. But like fishing, you don’t have to catch anything to still have a good day on the lake. And these men loved to ‘fish’.

“The old Army cameras, you know, took great pictures but were difficult to deal with” said Paul Berkowitz a motion picture photographer who served with the pictorial company. He was and still is ‘Berks’ to his friends. Berks grew up knowing he wanted to make movies but never imagined doing it for Uncle Sam and in the heat of battle. “You really had to know your skills. Shutter speed, ASA, exposure, all the variables you had to put together to get a good picture. And, the equipment was bulky and heavy because you’re dealing with a large format.”

He described the Filmo motion picture camera he used most frequently. “It had fixed focus lenses, which were difficult to deal with, but you could deal with it. And there were three of them on a turret, no zoom lens or anything like that. The main thing was when you were out in the field in the jungle or wherever you were, that camera was going to run, even if you dropped it. You could probably hit somebody with it, if necessary, and it would still run.”

Tripods for the heavy cameras were available, but they were considered a health hazard.

"Carrying a tripod in battle is not recommended but it could be fashioned into a litter to carry your body to a medical aid station or morgue,” joked Sonny Craven who served with the 221st.

“…if they let the military do it, I’m sure it would have been a lot different. Just let the troops go over there and stomp butt.” – Mike Boggs

The Vietnam War has been over for 50 years and on May 23, 2016, President Barack Obama visited Hanoi to announce new weapons partnerships and welcomed the former enemy as an ally in dealing with an increasingly ambitious and sometimes hostile common foe, China. Times change and with much distance, in fact, a lifetime between their service the men of the 221st have reached conclusions about both the larger meaning of this war and their role in it.

Chapter index:

1. OVERVIEW

Evan Mower’s opinions have an edge.

“It was a stupid waste of energy, talent and money and we haven’t learned anything by it.” Mower, who takes pride in his travels all over Thailand and Vietnam as both a staff and VIP photographer, is resolute.

For the others who took part in this project, the answers are more nuanced. Here’s what they had to say, in their own words, when we asked what it all means now, and was it worth the price?

Frank Lepore is philosophical.

“We are the product of all the little ingredients that go to make up our character," he said. "That can be the simplest of things. It can be an act of kindness. It can be the act of the most unspeakable cruelty. But all of that shapes us in some way. It makes us who we are. And if we’re smart we try to pass that on to our children… to the next generation. Don’t make the same stupid mistakes that we did."

Roger Hawkins, the trained engineer, is analytical in answering the question, with a question.

“We went into the war not knowing how it would turn out or what really was to be gained," he said. "So you can be an accountant and just look at it from an accounting standpoint. Was it worth it? Was what we spent in lives and money what we got from it?”

Mike Boggs, the career soldier, thinks militarily.

“If we’d have won the war things would have been a lot different, and we was on the verge of winning it. And it was so micromanaged by the White House and Johnson and everything that if they let the military do it – I’m sure it would have been a lot different. Just let the troops go over there and stomp butt.”

Guiding the conversation, Mark Casey asked of Boggs if today, Americans understand the war.

“They didn’t then. I think they know a little bit better now.”

Paul Berkowitz takes a historian’s view, the long view:

“All the stuff that we did is going to frame the debate about Vietnam for the next 100 years, 200 years. There's a written record, but the visual stuff has a truth to it that a historian can maybe make his own judgment and say, 'ah I heard about this, but look at this picture and look at this video and look at this film."

Throughout history, soldiers have been rewarded for their service with a stake, a claim on land in a new world or old, to which they could retire if they made it through alive. Mike Boggs is at that stage now, and if he thinks about the past, it’s in the context of what it taught him, and what he earned, and his will be our final words.

“I have no kicks," he said. "The Army pays me every month a nice little handsome retirement and I farm a little bit and me and my old bird-dog just get along and do what we want to. I just don’t get wrapped around the axel on a lot of stuff like a lot of people do.”

Chapter index:

1. OVERVIEW

This project originated with a simple request for coverage of the annual reunion of the 221st Signal Company (Pictorial), which took place in Phoenix May 5 to 9. 12 News, coordinating with former 221st Photo Team Leader Sonny Craven, arranged interviews with Paul Berkowitz, Roger Hawkins, Mike Boggs and Frank Lepore. Hearing their amazing stories and seeing the tremendous archive of photos inspired us to dig deeper into the proud history of 221st, the results of which you see here. We took every measure to let the principles tell their stories and to put a human face on one of our most controversial wars, still passionately debated today. The goal was to let their cameras “speak” and tell the tales of Vietnam, the people who lived it, and the lessons learned from that time.

About the photos

These photos were bought and paid for by the U.S. taxpayer and are in the public domain, meaning available for anyone to use. However, it’s not easy to find a photo. The 221st Paul Berkowitz offers this insight:

Much of the 221st Signal Photography, both still and motion picture, is preserved in the National Archives at College Park, Maryland; all of it in public domain. But to search for a specific photo is a daunting task generally requiring a visit to the Archives building. A way to search at home is on the website www.fold3.com. Here, free of any charges, there are about 40,000 Vietnam War images culled from the National Archives by volunteers and keyed into a highly searchable index. You can even search by a specific Photographers name.

ABOUT THE REPORTERS

Chad Bricks, Executive Producer of Visuals and Multimedia, 12 News

Chad Bricks is a Navy Veteran who joined 12 News two days after his honorable separation from the service back in 2008. He’s now the Executive Producer of Visuals and Multimedia, managing the photography team with some operational duties as well. From a family full of Sailors, Bricks joined the Navy at 18 years-old in the summer after graduating high school. He told the recruiter the only job skill he had was he was good with people. That simple description led to a career in photojournalism. He fell in love with the job.

Bricks' first duty station was a tour at American Force Network Naples, Italy. He learned to shoot, write and edit video there as well as dabble in radio. Two years later it was onto the USS Belleau Wood (LHA 3) where he made his first deployment in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom. His follow-on duty was at Navy-Marine Corps news in Washington D.C. where he volunteered for a deployment to Iraq. The Navy and Air Force were combining to relieve the Army at American Forces Baghdad. He was tasked to serve 6-months and volunteered to stay on longer. The first half of his tour was spent all over the Iraqi conflict. He told stories in every region from Fallujah and Ramadi to Mosul and all the way East to the Iraq-Iran border.

After a life of traveling, he now considers 12 News and Arizona his home.

***

Charles Gray, Executive Producer of Digital Operations, 12 News

Charles Gray joined 12 News in 2014 as Digital Coordinator responsible for launch of both the 12 News app and 12news.com and is now the EP of Digital Operations. He brings a deep understanding of digital media and journalism to his work. Charles was Digital Director for Raycom Media and part of the team at theglobe.com, one of the early social media companies. He was also a TV reporter at WTOC in Savannah, Georgia. Charles earned a BA in English Literature at Columbia University in New York.

***

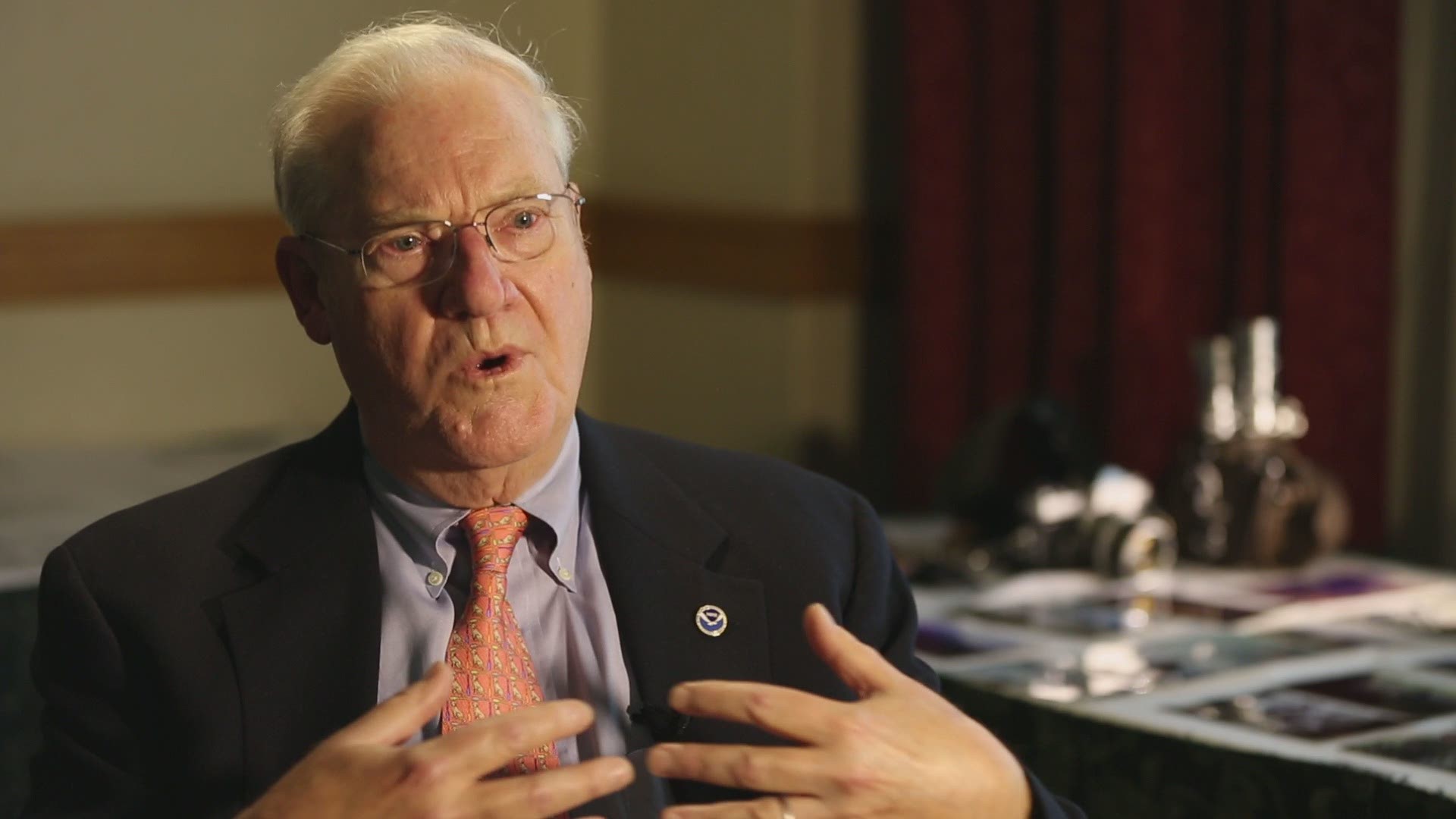

Mark Casey, Vice President and Station Manager, 12 News

Mark Casey most recently served as Vice President and Station Manager of TEGNA-owned KPNX-TV/KNAZ-TV (12 News) serving, Phoenix and Northern Arizona. He led News and Technical Operations for the NBC affiliate in the nation’s 12th largest television market, its satellite station in Flagstaff, AZ, and a 24-hour weather channel. 12 News produces 40 hours of local programming each week. As a digital and social force powered by 12 News and 12news.com, KPNX has the fastest growing digital news site and is consistently the top social platform as measured by engagement in the Phoenix market.

The Pittsburgh-area native has worked in broadcast journalism as reporter, photographer, show producer, field producer and news manager. He’s served in 10 markets at properties owned by Cox Enterprises, 21st Century FOX, the Walt Disney Company and TEGNA Media, formerly Gannett Broadcasting. Casey’s stations are consistently ratings and community leaders. He has made community advocacy a centerpiece of his work, using the reach and prestige of his stations as partners, sponsors, promoters, and creators of many community service events.

Special thanks to the heart of the 221st Signal Company (Pictorial) who provided their time, insight, memories and photos to this project.

- Paul Berkowitz

- Peter Berlin

- Mike Boggs

- Sonny Craven

- Roger Hawkins

- Frank Lepore

- Evan Mower