REHOBOTH BEACH, Del. (The News Journal) -- A local archaeologist was searching for the remnants of a 17th-century home near Rehoboth when he stumbled on a discovery that could rewrite chapters of Delaware history.

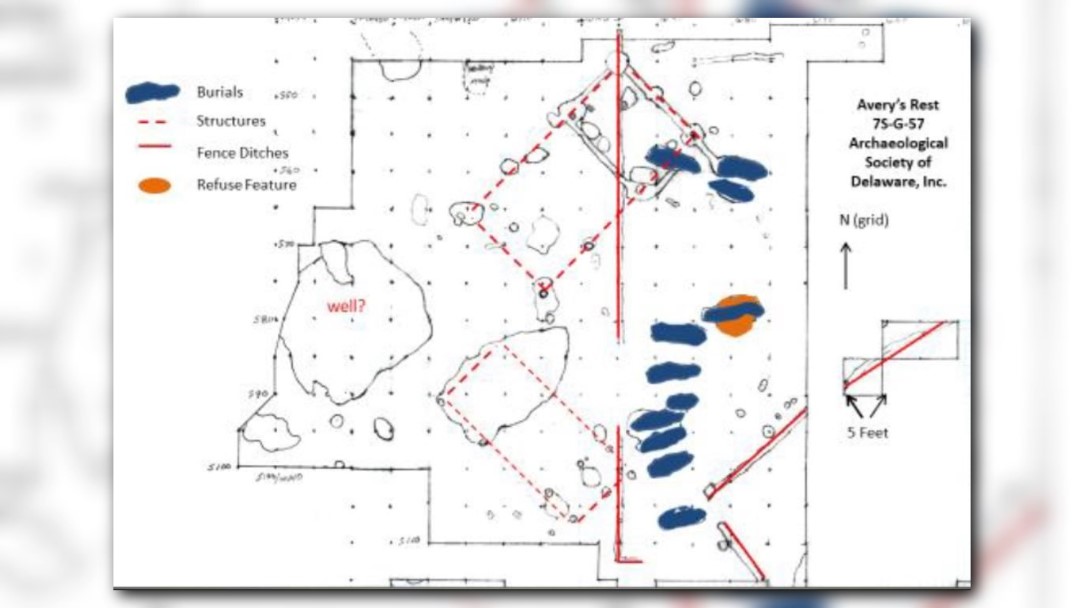

Dan Griffith was following a centuries-old fence line at Avery’s Rest, once an 800-acre colonial farmstead near Rehoboth Beach, when the trail led him to a burial site containing some of the First State’s earliest settlers.

“We were looking for something else,” the Frederica resident said. “That’s typical of archaeology.”

Griffith made the discovery in 2014, more than three decades after his first visit to the site. He quickly contacted state officials when he unearthed bones, sending along a photograph labeled, “Burial No. 1.”

Then came No. 2. Then No. 3.

Griffith and his team of volunteers eventually uncovered the unmarked graves of 11 people who once braved the New World in the marshy brush of southern Delaware.

Among those settlers, archaeologists found the earliest known grave site of African Americans in Delaware.

Two of the three African Americans were likely slaves of the site’s first occupant, John Avery. The third was a child about 5 years old, whose remains are the worst preserved skeleton at the site due to a burrowing groundhog.

Archaeologists and historians say the find could push the frontier of what they know about the people who made up the Delmarva Peninsula's early settlers.

“The potential for future research and the potential to connect this find with the stories of the lives of these people is really breath-taking to think about,” said Tim Slavin, director of the state Division of Historical and Cultural Affairs. “This place kind of reframes our whole interpretation of African-American history in Delaware.”

Griffith estimates the 11 people buried at Avery’s Rest, which also includes two women, six men and an infant of European descent, were buried sometime between 1665 and 1695. The eight Europeans are buried separately – and were likely buried later – than the three African Americans, he said.

“[The entire burial site] was totally unmarked and unknown,” Griffith said. “When we got there, it was just a fallow field. It was quite an adventure.”

Questions remain about who those people were and where they came from.

Now, experts at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History are beginning to unearth those answers using DNA and comparative analysis of other colonial grave sites throughout the Chesapeake region.

Dr. Doug Owsley, one of the top forensic anthropologists in the world, hopes to learn more about the movements of America’s earliest settlers by studying the 17th century remains found at sites like Avery’s Rest, historic St. Mary’s City in Maryland and the early settlement at Jamestown, Virginia.

“We’re working ... to tell the Chesapeake story from a different perspective that’s truly from the people themselves,” he said. “It’s just so fascinating when you’re talking about the 17th century and how much was not recorded about the lives and origins of the people themselves.”

The remains have been removed from their graves and are being studied at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C. Delaware historians, meanwhile, are planning a future exhibit to highlight the discovery.

From the remains, Owsley can determine sex, age, diet, health conditions and the extent of the physical demands of the lives of these early settlers. Because the sandy soils near Rehoboth Bay helped preserve the skeletons, facial reconstruction modeling is a possibility – allowing scientists to learn not only who the people were but also what they looked like.

“When all is said and done, I feel we will have a number of these individuals identified by name,” Owsley said. “This is a spectacular site.”

Searching for identities

The first recorded inhabitants of Avery’s Rest were John Avery and his family, who moved there in 1674 and tamed the wilderness into a farmstead.

At that time, the British were firmly in control of the area, which previously was ruled by the Dutch. Technically, the region then was still Pennsylvania. It would be another century before Delaware became the First State.

“When it became more stable politically, [Avery] moved up there and then became a member of the court in Lewes,” Griffith said. “The Dutch are still in town, and you’re really seeing the first European colonization along the coast.”

At that time, Lewes was known as Whorekill and Avery was known as a boisterous, foul-mouthed drunk among his fellow judges. Whorekill – the word "kill" in Dutch means creek or river – was the first settlement in Delaware, occupied by the Dutch in 1631.

Griffith and Owsley don’t believe Avery, who died in 1682 when Whorekill was renamed Lewes, is buried at Avery’s Rest. It is possible that his wife, Sarah, and one of his daughters were laid to rest there. At least four of the Europeans – the two women 50-60 and 35-45, a man about 30-40 and a 5-month-old baby – are related to each other in some way, DNA evidence has shown.

“The amazing thing is there’s such new capability in science,” Owsley said. “You could not have done this five years ago.”

Around the time the Averys moved to the site from Maryland, there were less than three dozen homes near Delaware’s beaches, most in the Lewes area. Today, only a small portion of the privately owned site where the burials were found remains undeveloped.

The Averys harvested corn, wheat and tobacco. Evidence suggests they grew some of the first imported peach trees. They also raised a lot of cows and pigs – far too many for one family to consume, Griffith said.

“There’s evidence his wife billed the courts for 2.5 tons of pork they hadn’t paid for,” Griffith said.

Historical documents also note Avery had two slaves, possibly the two African-American men buried feet away from the Europeans.

While their identities are still a mystery, it’s clear the people buried at Avery’s Rest did not have easy lives. Almost everyone found at the site suffered from poor dental health and back problems, evidence of a corn-based diet and life of labor.

Two of the people, a white man about 35-45 and an African American man about 27-37, had skull fractures that may have contributed to their deaths.

Avery’s Rest also marks an early period of African slaves coming to the Mid-Atlantic.

The three African Americans buried at the site are not related, and evidence suggests they had lived in the Mid-Atlantic region for most of their lives, Owsley said.

Their maternal lineages connect to West Africa, but also trace back to central and east Africa, offering insight into the transatlantic slave trade.

“It adds even more complexity to our understanding of how people were moving around and where they were coming from,” said Dr. Angela Winand, who heads Delaware Historical Society’s Mitchell Center for African American Heritage and Diversity Program. “It complicates our understanding of the development of Delaware as a state in that colonial period.”

A 'spectacular find'

The Cape Region was a new frontier for European settlers long before Delaware’s coastal towns became booming hubs for tourism.

Nestled among housing developments and crowded roads, Avery’s Rest has revealed artifacts from the mid- to late-1600s and early 1700s and revealed details about a life that included heavy farming labor, trade with Native Americans and a lot of tobacco smoking, as evidenced by stains on the teeth of the recently discovered remains.

“This is a frontier site, with people out there in the hinterlands,” Owsley said. “Here you’re learning about some of the first people in Delaware.”

Griffith first discovered Avery’s Rest in 1976 when, as the state archaeologist, he set out to survey areas of historical significance under threat from development.

At that time, the land was still in agricultural use. The Harmon family had farmed there since the 1920s, occasionally coming across an arrowhead or smooth stone they’d admire without much thought.

Waymon Harmon, now 75, remembers playing in the fields as a child and making those discoveries. As an adult, he farmed the land, planting corn and soybeans – not unlike the people who had lived there more than three centuries earlier.

“I was born right across the road from there and I played all around the area out in the field,” said Harmon, who granted archaeologists access to his private property for their excavation work.

“I used to farm right there,” he said. “I didn’t know it was there but I thought it was quite possible.”

After his initial foray, Griffith did not return to the site again until about 2006, a year after he retired from his state job. Development in the resort area was ramping up and a mad rush to collect as many artifacts as possible was underway.

The economic downturn a few years later gave members of the Archaeological Society of Delaware a little more time to work. By 2010, Griffith and a crew of volunteers had collected so many artifacts they had to stop working in the field and start cataloging their finds, including a 17th-century cellar and two wells, beads, buttons, coins, oyster and clam shells, pipe pieces and agricultural tools.

“It’s the beginning of the English spreading across the countryside,” Griffith said.

The burials were discovered in 2014 as society members continued searching for the house they knew had to be on the site. That’s when they called in the state and the Smithsonian to assist.

Officials have waited until now to announce the burial site because they wanted to wait for the results of initial studies on the remains. They also wanted to protect artifacts from looters and avoid trespassing on the private property while site work was underway.

By the time their excavations were complete, Griffith handed over 219 boxes of shell, brick, bone and other artifacts to the state, while the 11 skeletons were sent to the Smithsonian.

Researching centuries-old genealogy is no easy feat for historians. And tracking down the stories of 17th-century African Americans has posed a nearly insurmountable challenge for decades.

The wealth of information uncovered at Avery’s Rest may change that for Delaware and help put the state's history in better context among the story of the nation as a whole.

“It’s another occasion for placing us on a world stage and international stage in a way we don’t often think about,” Winand said. “Being part of those trade networks is essential to why the colony was created and established.”

Contact reporter Maddy Lauria at (302) 345-0608, mlauria@delawareonline.com or on Twitter @MaddyinMilford.